A decade in, Palestinian family fights on against East Jerusalem eviction

Who is trying to evict the Sabbagh family from their home in East Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood? That’s what Sami Ershied wants to know.

Ershied is a lawyer representing the family who have lived in the area since 1956. They have been fighting in court for over a decade - since they were served their first eviction notice in 2008.

It looked like the 32 members of the family would finally lose their home after the Israeli Supreme Court rejected their final appeal in January.

The family, using documents obtained from Ottoman archives in Turkey, had wanted the court to revisit the question of the original ownership of the land, but judges reportedly refused to discuss their claim.

This March, the family was served yet another eviction notice. But they challenged it and won a temporary freeze on the basis that earlier rulings were unclear about which part of the property - which has been extended over the years - should be abandoned.

Earlier this month, Ershied asked the court to cancel the eviction altogether. The family is awaiting a date for a hearing on this request and they can live in the house until then.

One of the main questions that the Sabbaghs seek to untangle is who exactly is trying to push them and other families out of their neighbourhood.

In 2002, a group of Jewish investors assembled by the Homot Shalem association bought the land on which the Sabbagh home sits for $3m from two religious trusts.

'Who is spending so much money to finance the settlement industry in East Jerusalem?'

- Sami Ershied, Sabbagh family lawyer

Shortly after, the new owners transferred the property to Nahalat Shimon Ltd, a US-based company that wants to “regenerate” Sheikh Jarrah and build 200 housing units for a Jewish neighbourhood where the Palestinian homes now sit.

But who owns Nahalat Shimon and who has been evicting Palestinians to make way for the project is unclear.

At a recent hearing of one of the 11 households currently faced with eviction, Zachi Mamo, a Nahalat Shimon manager, acknowledged that he didn’t know who was paying his salary and is not entirely sure where the company’s offices are located.

Nevertheless, Ershied said he believes this is something those involved have a right to know about before any further developments take place in their cases.

“Who is spending so much money to finance the settlement industry in East Jerusalem?” he asked. “Those are people who are affecting the daily political and diplomatic life in Israel, and we don’t know who they are.”

'We had a house in Jaffa'

The questions around Nahalat Shimon are only the latest in a long-standing dispute about ownership in Sheikh Jarrah.

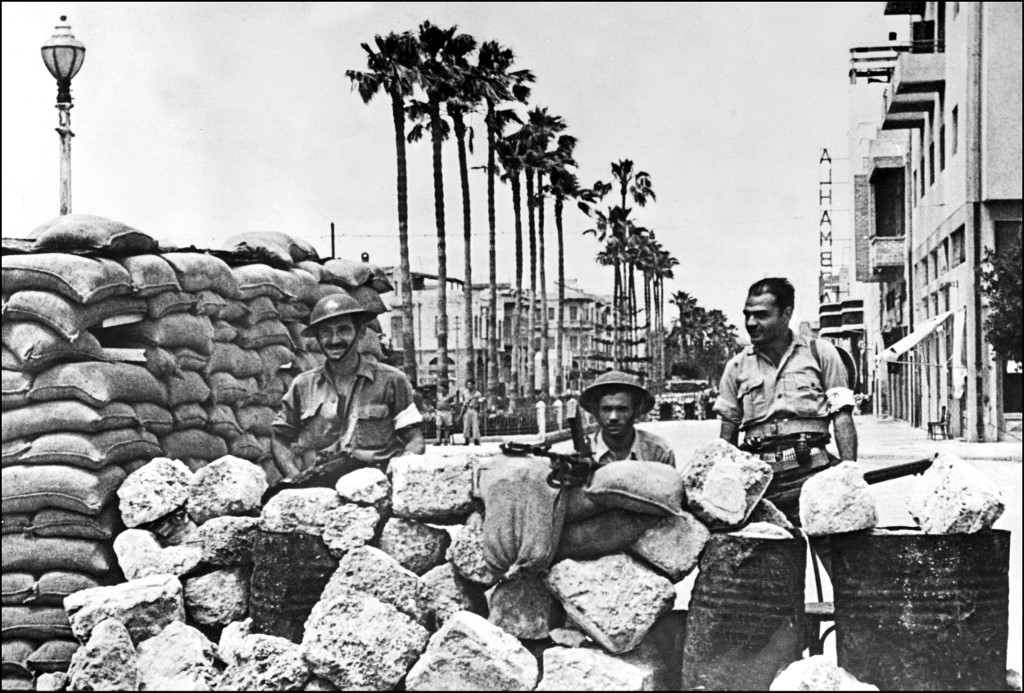

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Jewish communities living in the neighbourhood fled their homes and lands which they claimed to have bought during the Ottoman Empire.

Jordan took over administrative control of East Jerusalem and resettled - in cooperation with the UN Relief Works Agency - 28 Palestinian families, including the Sabbaghs, in the area.

“After losing our house in Jaffa in 1948, we stayed at relatives in Jerusalem until we signed the agreement with the Jordanian government in 1956,” Mohammed Sabbagh, 70, the oldest member of the family, told MEE.

The families were told that after they leased the homes for three years, they would receive the legal titles to the properties while the lands would be placed under Jordanian control.

But they were eventually only left with tenancy agreements. Jordan failed to issue the papers required to prove their legal rights to the homes before the Six Day War started in 1967 and the Israeli military occupied East Jerusalem.

Meanwhile, as Palestinians like the Sabbaghs have been prevented from returning to homes they left behind during the 1948 war, an Israeli law passed in 1970 says Jews who can prove they owned property in East Jerusalem before that year are able to reclaim their properties.

'Give us our properties back and we’ll leave Sheikh Jarrah'

- Mohammed Sabbagh, 70

Nahalat Shimon’s lawyer Ilan Shemer holds that the Palestinian families who have been living on the company’s property for decades have only been entitled to pass on tenancy rights to their relatives, not ownership.

In 1972, an initial agreement between lawyers of both parties recognised the Jewish community’s ownership of the land in return for a protected tenancy status for the Palestinian families living in the houses for up to three generations.

However, the lawyer representing the Palestinians did not ask for their consent during the negotiations and eleven families, including the Sabbaghs, decided not to sign. This is one of the reasons their lawyers argue they should not be evicted now.

“Our Palestinian lawyers went on strike because they didn’t want to legitimise the ruling of an Israeli court on an occupied territory. So we got an Israeli lawyer. He signed that agreement without notifying the families. For some it was unacceptable; my father didn’t sign up. We had a house in Jaffa. Give us our properties back and we’ll leave Sheikh Jarrah,” explained Sabbagh.

Letter of the law

Ershied contends that the Sheikh Jarrah eviction cases are discriminatory because the legal procedures do not take into account that East Jerusalem is an occupied territory.

Under international law, an occupying state cannot forcibly transfer residents of occupied territories because it has an obligation to preserve the demographic composition of the inhabitants.

Despite this, nine families have already been evicted since 2009 while a few are left fighting for their survival.

Amy Cohen, director of international relations and advocacy for the Israeli NGO Ir Amim, says the Israeli judicial system is following the law narrowly when it comes to attempts by settlers to establish Jewish compounds in East Jerusalem.

“They are not taking a stand on behalf of justice. They are just ruling on the letter of the law. We are seeing complicity with the settlement activities at all levels and stages within state policy and measure, although in terms of implementation, the action is taken by settlers," Cohen said.

Moreover, she argued, most of the Jewish families who lost their properties in 1948 already received compensation: if they succeed in the eviction process, they will be compensated twice; while the Palestinian families, and the Sabbaghs specifically, risk being made refugees again.

According to the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, private companies that are expanding illegal settlements pose a real threat to the international legitimacy of the state of Israel by using administrative claims that risk deteriorating a very delicate situation in East Jerusalem.

'We are seeing complicity with the settlement activities at all levels and stages within state policy'

- Amy Cohen, Ir Amim

“Through their actions, these entities are establishing facts on the ground that do not necessarily accord with the vital interests of the state of Israel,” a 2010 report from the institute said specifically about activity in Sheikh Jarrah.

Indeed, international observers from the Office of the European Union Representative, the British Consulate, but also numerous NGOs and activists regularly attend the Sheikh Jarrah court hearings to monitor what’s happening.

Before sending eviction notices, Nahalat Shimon is offering recognised tenancy to remaining residents if they accept the company’s ownership of the land.

“We want them to recognise our ownership or we want them out,” said Shemer during a court hearing this month. “If we evacuate them, they will be left with nothing…They are presenting the same case and documents as the Sabbagh family did, but this family has never won so far.”

Shifting public opinion

Their fight is not over. Ershied said the Ottoman-era documents from the archives in Turkey show that the Jewish communities who have previously claimed to own the land actually registered their ownership to property that is near, but not actually in Sheikh Jarrah.

So he is now trying to establish that earlier rulings were based on fraudulent evidence, although he acknowledges that it is unlikely a magistrates court will reopen the topic.

There is also the continuous search to learn who is behind Nahalat Shimon, details which would not necessarily prevent the eviction of Palestinian families in court, but could create a political debate that might shift public opinion.

“I don’t know if exposing the name of those people would change something on the ground: if the state didn’t want to have them there, they could not last a day,” said Ir Amim’s Cohen.

“Particularly in Sheikh Jarrah, we have seen a reinitiating of eviction procedures, once the Trump administration took over. Perhaps this information could make the difference in the future, with different governments in both countries.”

In the meantime, remaining Sheikh Jarrah residents are tormented, fearing they could be evicted at anytime. Private security paid by the development company patrols the area every day and the open spaces are filled up with security cameras, fences and guards.

“It is hard to be considered like a criminal,” said Mohammed Sabbagh, who keeps positive nevertheless.

“In the last 10 years, I have met people from all over the world who came for support. I learned English and how to speak in public. Someone one day told me I look like an actor. But I am just a simple man”.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].