Turkey and Libya sign maritime deal to counter Greek drilling

Turkey and UN-backed Libyan government on Wednesday signed a memorandum of understanding to delimit maritime zones in the Eastern Mediterranean in an attempt to block further Greek and Cypriot energy drilling activities in the area.

After two long meetings between Libya's Government of National Accord (GNA) Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the two sides reached an agreement on the delimitation of maritime zones as well as security and military cooperation.

Turkish experts and media hailed the memorandum on the zones as a victory against Greek and Cypriot plans in the Eastern Mediterranean. Pro-government Yeni Safak daily described the agreement as a “historic step” to stop “Greek exploitation” of maritime rules to conduct oil and gas drilling in the areas close to Turkey.

“We are hoping to sign similar agreements with other neighbours, except Cyprus, to fairly share rights in the area in terms of underwater resources,” Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said on Thursday in live remarks.

“We took this step to preserve Turkey’s rights.”

The deal follows the imposition of EU economic sanctions against Turkey two weeks ago to punish it for drilling near the coast of Cyprus in violation of a maritime economic zone established off the divided island.

Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias said any maritime accord between Libya and Turkey “ignores something that is blatantly obvious, which is that between those two countries there is the large geographical land mass of Crete.

“Consequently such an attempt borders on the absurd.”

In June, European Union leaders warned Turkey to end drilling in waters around the island or face action from the bloc, and EU foreign ministers agreed on economic sanctions against Ankara earlier this month.

Tensions have been running high in the region since Cypriot and Greek governments started issuing hydrocarbon drilling licenses in recent years.

Turkey has said the Greek Cypriot authorities have been exploring in waters that either belong to Ankara or where Turkish Cypriot authorities would have a right to any discoveries.

Earlier this year, Ankara sent its own drilling ships to the area to signal that it did not recognise Cyprus' declared exclusive economic zone.

Chief of staff of the Turkish Navy, Rear Admiral Cihat Yayci, had called on the Turkish government to sign a memorandum with Libya to block Greek efforts in the Eastern Mediterranean.

He claimed in his book on the issue that such a memorandum would hinder a possible agreement between Greece, Cyprus and Egypt on an exclusive economic zone.

The three countries, with the backing of Israel and the United States, have been closely working to find ways to cooperate on energy in the Eastern Mediterranean, including creating a regional gas market.

Egypt called Thursday's deal "illegal and not binding or affecting the interests and the rights of any third parties".

Hasan Unal, a professor on international relations at Istanbul-based Maltepe University, told Middle East Eye that the memorandum was indeed historic in the sense that it would frustrate Greek plans.

“Greece has been granting drilling licences for some time near Crete island as a fait accompli. Now this has been nullified,” he said. “The Greek Cypriot government would also need to reconsider its activities in the west of the island, since their claims on the area were invalidated by this memorandum.”

Turkey and Greece are allies in NATO but have long been at loggerheads over Cyprus, which has been ethnically split between Greek and Turkish Cypriots since 1974, when Cyprus was divided after a brief Greek-inspired coup triggered a Turkish invasion.

The Republic of Cyprus in the south of the island is a member state of the EU, while the north of the island is controlled by the Turkish Republic of Cyprus which is only recognised by Turkey.

Several peacemaking efforts have failed and the discovery of offshore resources in the eastern Mediterranean in the 2000s has complicated the negotiations.

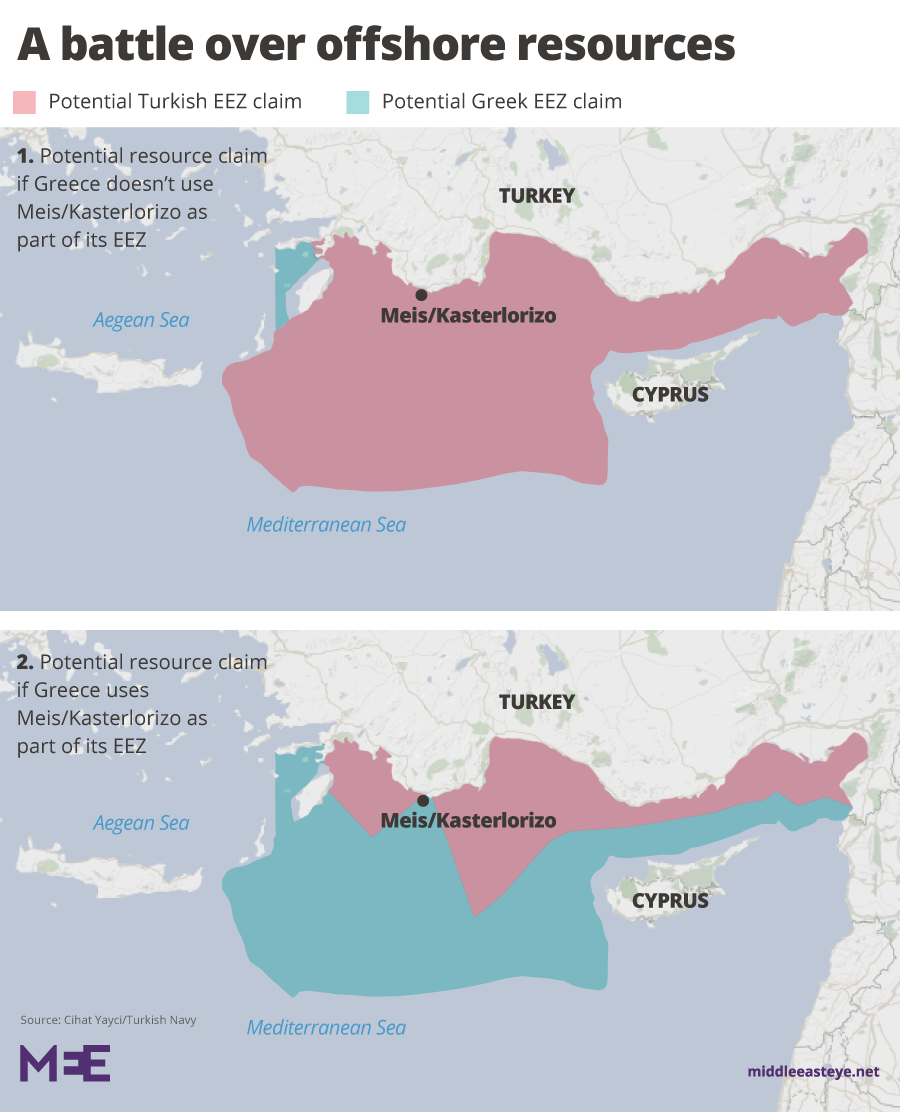

According to the UN Law of the Sea, coastal states have a right to 320km of maritime territory from their coast or a baseline drawn off their coast where they can declare an "exclusive economic zone" (EEZ), and where they have the right to explore and exploit natural resources.

However, because of the concave shape of the Eastern Mediterranean, there is an overlap between the areas that each country can claim, requiring negotiations and compromise – and opportunity, some say – for leverage in ongoing conflicts.

Neither Turkey nor Greece have made official EEZ claims, but that has not stopped them from fighting over the territory they envision to be their own.

Athens has suggested that it could base its claim to an EEZ on the location of the island of Kasterlorizo, known as Meis in Turkey, which is just two kilometres off the coast of Turkey. Such a move would reduce the area that Ankara could claim as its EEZ from about 90,000 square kms to 26,000 square kms.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].