Netanyahu's annexation of Jordan Valley already a reality, say Palestinians

Amid a flush of pale orange light, the eastern slopes of the West Bank mountains flow down towards the Jordan Valley at noon.

At the foot of the desert hills lie the scattered zinc houses and tents of a Bedouin camp.

Several schoolgirls walking down a dirt road pass by a little boy guiding a small herd of sheep back to one of the barracks, where 32-year-old Farhan Ghawanmeh checks a water tank.

“We bought this tank two weeks ago and it is half empty already,” Ghawanmeh explained.

“We used to buy water from the nearby town of Al Awjah. Now even people in Al Awjah have to buy water themselves.”

Ghawanmeh’s community is composed of 120 Palestinian families, totalling between 750 and 800 people.

They are refugees from the northern Naqab desert, forced off their lands by Israel in 1948.

Since then, they have lived in the Jordan Valley, classified under Area C since the Oslo accords of 1993.

That means they are under the direct authority of the Israeli occupation, surrounded by Israeli settlers on all sides. Settlers, who never lack water, occupy the space where Ghawanmeh’s family used to graze their sheep, not many years ago. Settlers who live and act as if they were living in the state of Israel.

'Systematic segregation'

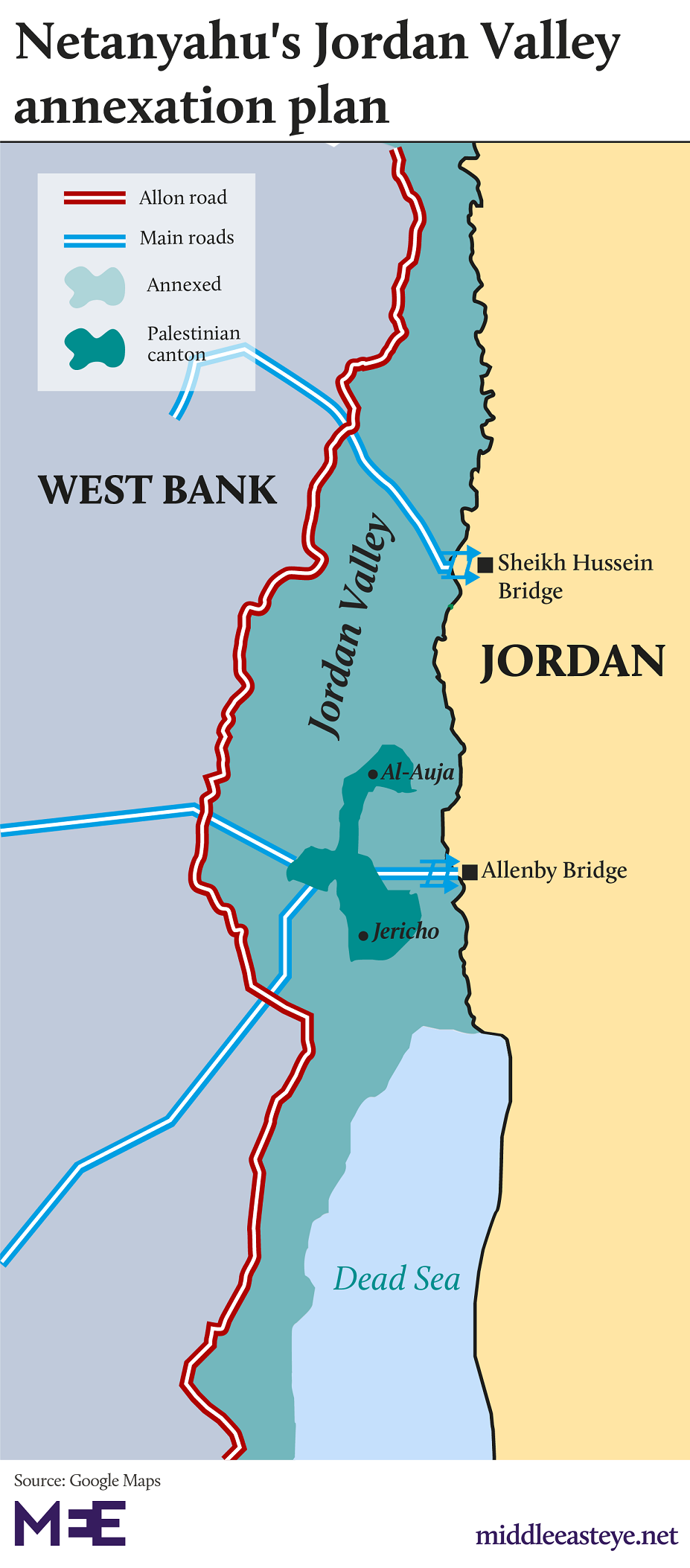

In September, one week before the Israeli elections, Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced his plan to annex the Jordan Valley if he won.

On Thursday, in the International Criminal Court's (ICC) annual report, ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda expressed concern over Netanyahu's proposal.

In response, Netanyhau told Israel's Haaretz newspaper that it was Israel's full right to annex the Jordan Valley if it chose to do so.

He also said he had spoken to US President Donald Trump earlier this week about the annexation.

The electoral promise has put the subject of annexation back in the forefront of international interest.

However, despite the official European rejection of Netanyahu’s declaration and the condemnation by the Arab states, for Palestinians like Ghawanmeh, Israel's annexation is more than a political aspiration. It is a daily reality.

A reality that is “systematically reinforced and advanced by Israel,” according to Maha Abdallah, legal researcher at the Palestinian human rights organisation Al-Haq.

“Most aspects of annexation are visible already in the West Bank,” said Abdallah.

“The most obvious of these aspects is the settlement-building and the infrastructure linked to it.

"But there is an entire process of legal, economic and administrative annexation.”

In 2017, the Israeli parliament, the Knesset, passed a law for the “regularisation” of the West Bank settlements.

The law allowed the retroactive legalisation of settlements that had been built outside of Israeli law.

This means that whenever settlers have extended their control, the occupying state would provide them with infrastructure, services and protection, all of which Palestinians are excluded from.

Faris Fuqaha, Al-Haq's field researcher in the Jordan Valley, explained that “the Israeli settlement industry always comes at the expense of Palestinians living in Area C. It is a systematic segregation".

Living without water

One of the most obvious aspects of this segregation is the most basic elements of human life: water.

Ghawanmeh’s community, for instance, located its Bedouin camp decades ago near the Palestinian town of Al Awjah, building it on the lower ground of a natural water spring.

“The villagers had built a small canal to take the water from the spring to the village,” explained Fuqaha.

In 2003, the Israeli authorities installed an artificial well beside the spring to extract its water, in order to pump it up to the nearby illegal settlement of “Kokav Hashahar”.

Today, the village canal is dry. Palestinians in Al Awjah and the surrounding areas have to buy their own water from the Israeli water company Mekorot.

According to the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem, there are around 40 similar wells across the West Bank, providing Israelis with a daily consumption rate ten times that of the Palestinians.

“We buy water in these tanks of three cubic metres each,” said Ghawanmeh, as he checks the half-emptied tank.

“It costs us fifty shekels per cubic metre, 150 shekels the tank [£33], which is very expensive.”

The Israeli water pipes that pump the water up to the settlement pass just a few hundred metres from the Palestinian community’s houses.

“Last week, a young man from our community tried to take water directly from the pipes,” Ghawanmeh said.

“The Israeli army came and arrested him. He is now in prison and will be facing the military court soon.”

Accelerated legal discrimination

Justice segregation is another aspect of Israeli annexation.

“Indeed, Palestinians in Area C are judged by Israeli military courts even for a driving penalty, whereas Israeli settlers are judged before the Israeli civil courts,” says Abdallah.

“When it comes to land disputes in the West Bank, it is the Israeli Supreme Court that rules.”

But for Israeli leaders, the judiciary system in Area C is not discriminatory enough.

'When it comes to land disputes in the West Bank, it is the Israeli Supreme Court that rules'

- Maha Abdallah, Al-Haq

In 2017, Ayelet Shaked, then Israeli minister of justice, introduced a bill to transfer the jurisdiction of land disputes to Israeli district courts - where the burden of proof is on the plaintiff, not the defendant.

In other words, settlers would no longer be required to provide any proof of legality when they took land.

Instead, it would be Palestinians who would be required to prove their ownership of their land, if they wanted to defend it in the Israeli courts.

This inverted logic makes Israeli settlement and land-grabbing the rule, and makes the Palestinian presence and land ownership the exception.

If passed and adopted, the law would be a big step to full annexation.

Ambulances not allowed

But legal discrimination goes further. Palestinians are forbidden from building anything in Area C or improving their conditions of life there.

Although electricity cables hang from towers across the hills near Al Awjah, Bedouin communities depend on tractor batteries for light, as most families cannot afford solar panels.

Ghawanmeh explained that “the nearest hospital to our community is in Jericho and ambulances cannot come here.

"When there is an emergency, we have to look for a car within the community or call someone from Al Awjah who has a car.

"The same goes for education. Our children have to travel three to six kilometres to school every day.”

Ghawanmeh recalled that “in 2010, when we tried to establish a school in the community, with the help of an international NGO, the Israeli army came and confiscated the barracks that were supposed to be the classrooms”.

Fuqaha highlights that Palestinian towns, villages and Bedouin communities in Area C are not allowed to expand their urban area

“Every building is monitored by the Israeli authorities. The community may expand the space of a barrack or a tent," said Fuqaha.

"However, if a new building is started in a new location, within the community or outside of it, it is demolished, while tents are confiscated”.

'Nothing is an eventuality!'

Forbidden from building, accessing water or receiving justice, education, health or energy, many Palestinians find no other option but to leave.

“Many young people who cannot work after finishing their studies look for a way to leave," said Ghawanmeh.

"They go to towns and cities in the A and B Areas, and many take their families with them.”

'Many young people who cannot work after finishing their studies look for a way to leave'

- Farhan Ghawanmeh

Under the Oslo accords, the Palestinian Authority was granted limited powers of governance in Areas A and B. In both areas, Israeli authorities have full external security control.

As Abdallah explains: “The Israeli colonisation creates coercive environments for Palestinians, in order to force them to leave.

"Israel wants to annex the land, exploit its natural resources, its touristic potential and agricultural capacity. It does not want the people.”

This places a question mark over the destiny of Palestinians in Area C if annexation becomes official.

Their legal status, their rights and their future in their land, is uncertain. Such is the opaque horizon that Palestinians face in what represents more than 61 percent of the West Bank’s territory.

An irreversible eventuality for some, but not necessarily for Ghawanmeh. For him, there is another way ahead. “Sumoud (steadfastness), brother!” he exclaimed, as night fell on the slopes of the hills of the Jordan valley and glimmering lights, coming from the scattered houses along the now dry canal, joined his voice.

“As long as we are still here, nothing is an eventuality.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].