In pictures: Iran's silk makers still weaving a 3,000-year-old trade

The memory of the Silk Road is still alive in the remotest regions of Iran, where the ancient route once passed. For more than 3,000 years, silk thread produced in Iran has been used to make clothing fabric and for weaving Persian rugs. Thousands of families in northern and eastern Iran still earn a living through the ancient trade, mainly in the Gilan, Razavi Khorasan, and Torbat-e Heydarieh provinces (All images MEE).

It was from his father that 47-year-old Gholamreza Mohammadi learnt how to unravel silk filaments from silk cocoons. Every day, Mohammadi spends between four and five hours reeling silk in the dark and damp workshop at the end of his courtyard.

Like Mohammadi, all 110 families in the small village of Bask, around 1,000 kilometres northeast of the capital Tehran, make a living producing silk thread.

In many of these small villages along the Iran-Afghanistan border, families receive the cocoons of live silkworms in wooden boxes from wealthy silk traders who also pay their salaries. The cocoons are then soaked in hot water, which loosens the filaments so that the raw silk threads may be extracted.

Silk cocoons are produced in the northern provinces of Iran. They are also imported from Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan for around 2m Iranian rials (roughly $17) per kilo. But villagers like Naghizadeh do not have the financial means to buy or import the cocoons themselves, so they rely on silk traders for the supply.

In the past, silk threads would be wound round the spindles by hand. Today, this process is powered by electric machinery, but most of the rest of the process is still done manually. While there are industrial silk factories in Iran, at smaller workshops like Mohammadi's, little has changed in the traditional craft for hundreds of years.

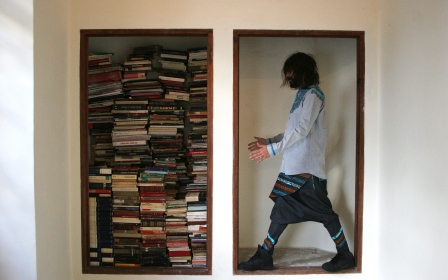

“It’s a difficult job," says 50-year-old Asghar Naghizaded, who has been producing silk threads since he was 13, when he was still in high school. It is a profession these villagers have dedicated their whole lives to. "But the main benefit of that goes in the pockets of the masters [silk traders]; we are just the labourers,” Naghizaded says.

And it is indeed a long-winded process. According to another silk producer in Bask, Hojjat Amini, an entire family of four people or more might work for 12 hours straight to produce one kilogram of silk thread.

This earns them around 50,000 Iranian rials (roughly $0.41). In contrast, one kilo of silk thread can fetch more than 100-fold on the market, at around seven million Iranian rials (roughly $58).

After the extraction, the individual threads are then woven together. This stage of the process is usually handled by women working in their homes.

Each member of the family plays a role in the process. Nine-year-old Shir-mohammad helps his mother with the final stage of the silk thread production, where several threads are gathered together to form bundles.

According to Iran's head of Sericultural (silk farming) Centre, Adil Sarvi, Iran is the eighth largest silk producer in the world, after China, India, Uzbekistan, Thailand, Brazil, Vietnam and North Korea, with an annual production of 120 tonnes of silk a year.

Iran's agriculture ministry offers loans to villagers with small workshops who choose to produce silk or rear silkworms.

The process involves minimal waste - even the silkworms are dried and used as fish food. The traders allow the villagers to dry and sell the silkworms as they please.

These bundles of finished silk thread, held in Mohammadi's wife's hands, are the product of around a week's work. Every month, the silk traders come to the village and collect the silk threads which are now ready to be steam dyed.

The Silk Road was a well-connected network of routes which, according to ancient maps, began in China and passed through central Asia before ending in Syria. It served as an important trade route connecting the Mediterranean Sea and China.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].