'We have no dreams': Rohingya despair after deportation from Saudi Arabia

As he scanned the Bangladeshi hills for the first time, Mohammed Faruque thought about how quickly he'd lost everything he'd spent years working for.

He was stepping off a bus empty-handed, joining his family in the foreign land they now lived in as refugees, a city of plastic sheeting in place of the ancestral villages that had been home in Myanmar.

'What will I say when I reach my home? How can I show them my face?'

- Mohammed Faruque, Rohingye deportee

Faruque, 25, and scores of other Rohingya have been arriving in Bangladesh throughout the past year, released after months and years spent in Saudi detention centres after they had sought prosperity and opportunity in the Gulf kingdom.

For many of them, the deportation to Bangladesh - a country most had never lived in before - has placed a heavy burden on their mental and emotional health as they adapt to life in the world’s largest refugee camp, banned from working, education and travel after the freedom Saudi Arabia briefly offered.

"On the bus as I was travelling, I felt like jumping from the window to the street. What will I say when I reach my home? How can I show them my face?" Faruque told Middle East Eye.

“Arriving here was weird for me... for four days, I couldn't speak to anyone. The situation made me dumb – I couldn't say anything.”

He has barely settled since then. He has been unable to work and spends his days lying in the darkness under the tarpaulin sheeting that, combined with a bamboo frame, has become his home. When he arrived, he whiled away the empty days on his phone, talking to friends through messaging apps - but in August last year, Bangladesh cut off internet access to the Rohingya.

Contrasting the sense of empowerment he had working in Saudi Arabia to the helplessness of refugee life has occasionally prompted thoughts of once again leaving his family to look for chances abroad, perhaps in Malaysia, where tens of thousands of Rohingya live. But the journey involves a dangerous boat voyage from Bangladesh and many have been arrested attempting it.

Asked how he is doing, he always has the same answer: "I am fine, physically, but not mentally."

Freedom promised, then lost

Like hundreds of other Rohingya, especially young men, Faruque left Myanmar for Saudi Arabia after communal riots in 2012 that forced more than 100,000 Rohingya into displacement camps and left others living under an aggressive security regime.

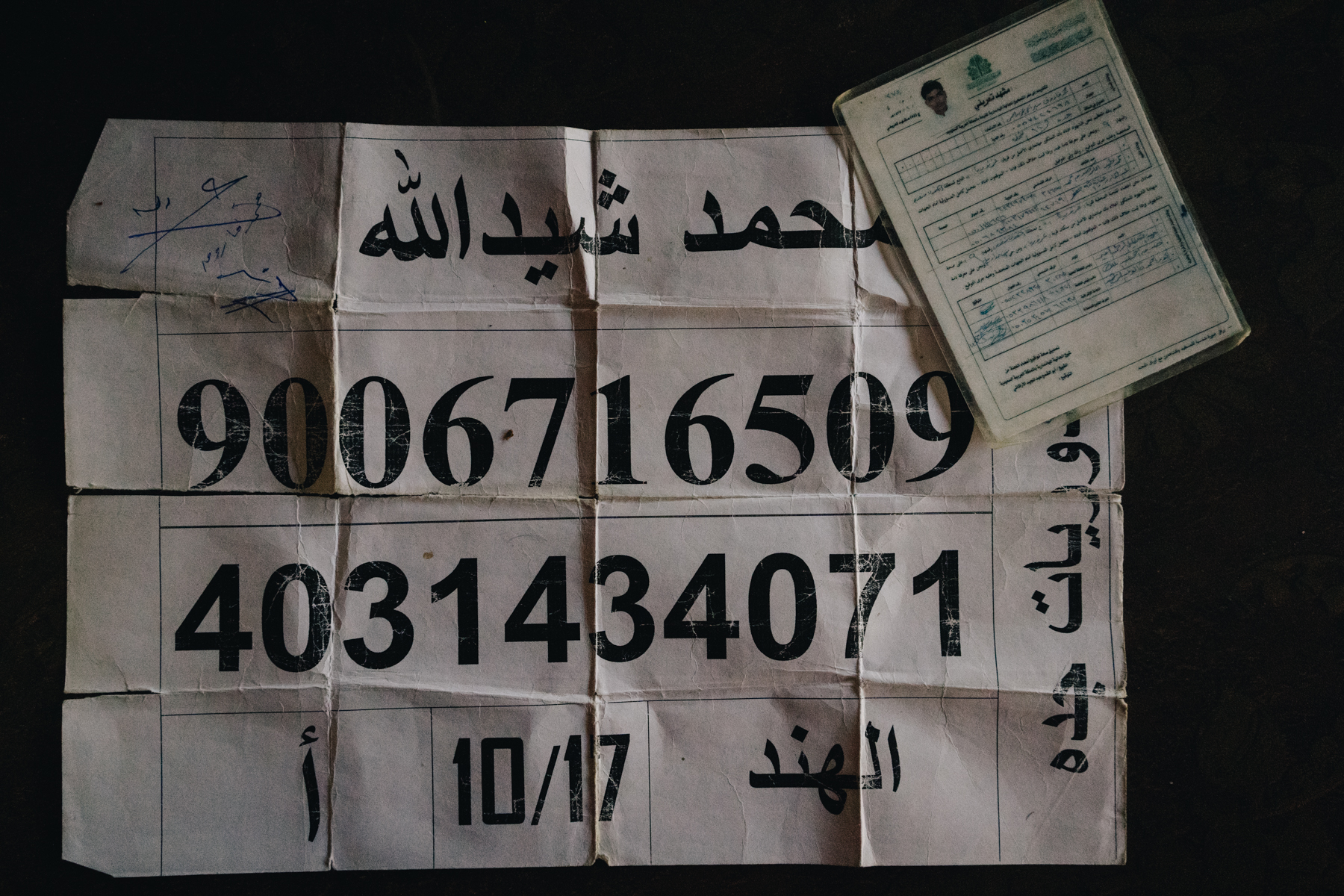

Denied citizenship in Myanmar since 1982, the Rohingya - a mostly Muslim ethnic group indigenous to western Myanmar - had to travel to nearby Bangladesh and bribe officials for passports to travel to Saudi Arabia, where they were told they would find sanctuary and opportunity under the rule of former King Abdullah.

For a while, Faruque found exactly that. He was able to work freely in factories and ascend through the hierarchy, making use of his self-taught English and sending whatever spare money he had back to his family in Myanmar, who used it to drag themselves out of poverty by buying land and livestock.

But the family lost it all in August 2017, when the Burmese military forced 700,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh, in a campaign the UN described as “genocidal”.

'When I heard my sons were killed, I cried for days. I felt helpless over there and wanted to come here to join them'

- Mohammed Faruque

Shortly afterwards, Faruque was detained by Saudi immigration police and sent to the Shumaisi detention centre, which was filled with Rohingya and other migrants who had been working in the kingdom without permits.

“After King Salman [took the throne], pity, humanity, compassion, finished. Zero now in Saudi Arabia. After 2014, after the death of King Abdullah,” said Faruque. Reforms instituted by King Salman's son, Mohammed bin Salman, made it harder for Rohingya to get residency permits and punished any who did not, despite the protection that had previously been afforded the minority group because of their statelessness.

Like many, Faruque bemoans this development. "It's a big tragedy only for Rohingya because Indians, Pakistanis, people from other countries can return happily to their country," he said. "Their embassies come to receive them. But for Rohingya, there is no one."

'I felt helpless'

As the Myanmar military advanced in August 2017, killing thousands of Rohingya and burning down their villages, the Rohingya diaspora working in places like Saudi Arabia constantly feared the type of call 65-year-old Bashir eventually received.

“When I heard my sons were killed, I cried for days. I felt helpless over there and wanted to come here to join them,” he said.

Bashir did not eat for a week. He had spent 20 years in Saudi Arabia, first working freely and even bringing his teenage son to join him, until the situation changed for Rohingya in the kingdom.

Bashir’s son was the first to be arrested; the father was detained not long afterwards on his way to work, at an immigration police roadblock on a route regularly used by commuting migrant workers.

Bashir presented an old residency card, one he had been given during the good times, but now found he could not get it renewed, and was carted off to Shumaisi.

They both spent months in the detention centre, under the constant glare of LED lighting and air conditioning that was never turned off. They slept on bunk beds and were denied access to fresh air and natural light.

Rejected by Myanmar, they had no consular support, which Rohingya activists estimate has resulted in hundreds of individuals spending years in Saudi detention centres, the only way out being by bribing brokers who arranged for fake Bangladeshi passports.

This was how Bashir essentially paid for his own deportation, spending all of his savings on securing the release of both his son and himself. He was taken, cuffed, to the airport and held in a room with other Rohingya until their flight to Bangladesh was ready to leave. When he arrived, he passed through immigration posing as a Bangladeshi and then immediately boarded a bus headed for the refugee camps.

“I realised life would be hard here,” he said. He returned to a family still becoming accustomed to their new lives, not only as refugees but without the two sons killed by the Myanmar army.

Internet cut

He has had to become used to an idle life, dependent on simple rations of rice and lentils handed out by the aid community to the one million Rohingya refugees now living in Bangladesh. Working is forbidden, apart from on some camp infrastructure projects where volunteers are paid a small stipend.

Some Rohingya earn a living as labourers in local small-scale factories or with farmers on land around the refugee camps, but that has also become more difficult in recent months after Bangladesh tightened security in the area.

'There are so many educated people like myself but here we feel useless. We have no dreams'

- Mohammed, Rohingye former migrant worker

The internet has also been cut off in the camp vicinity and phone and computers confiscated by police, disturbing some of the businesses young and innovative Rohingya were building up to fill the information and communications gaps in the camp.

It was into this environment that 27-year-old Mohammed arrived in September, deported from Saudi Arabia after six years.

Like Faruque, Mohammed had felt relatively successful during his first few years living in Saudi Arabia. He was able to send money to his family and lived with greater comfort than he had known in rural Myanmar, especially after the army implemented an almost-total ban on their movement, already tightly policed, after the 2012 riots.

Though he had lost that freedom when he was arrested, he was initially happy to be reunited with his family in Bangladesh. He thought he would be able to set up a shop in the makeshift camp market selling mobile phones and accessories and offering a variety of internet services most refugees would not be able to access themselves.

But the Bangladeshi internet ban has limited Mohammed to providing only basic services helping other refugees with applications for official purposes, like health permits, and providing printing services with a photocopier concealed at the back of his shop.

“There is no hope for the Rohingya people... wherever we go, we are kicked [out],” he said.

“There’s no hope for me. There are so many educated people like myself but here we feel useless. We have no dreams.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].