For Iran, retaliation is more than a matter of saving face

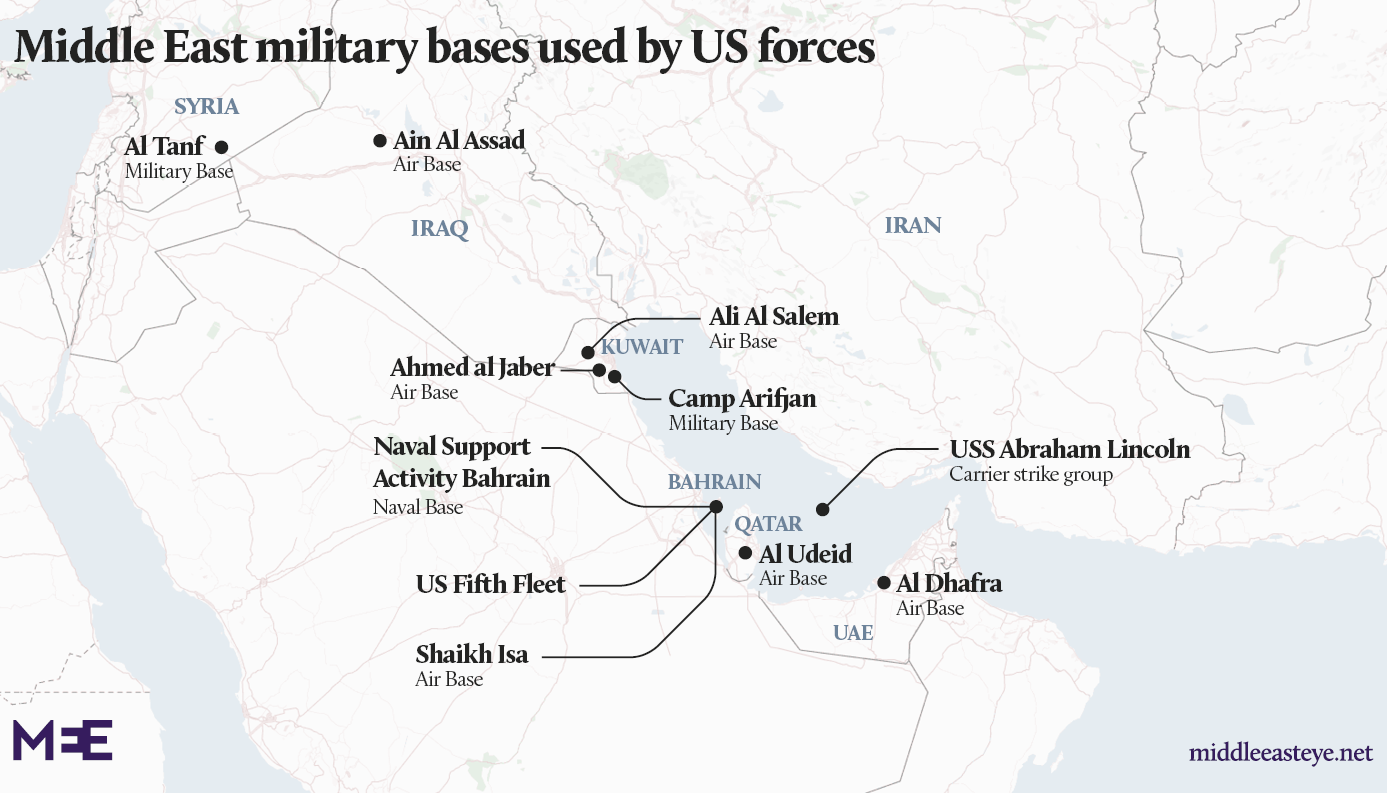

Hours before Qassem Soleimani was buried in his hometown, Kerman, on Wednesday, Iran launched multiple missiles against two US military bases in Iraq, in revenge for the death of the country's most senior general by an American air strike last week.

Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei said the missile attacks were "a slap in the face" for the US.

It's unclear whether there have been any casualties. Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) claimed responsibility for the attack, saying that it was in response to the United States' "criminal and terrorist operation", referring to the assassination. "We warn the Great Satan, the vicious and arrogant American regime, that any further malice or other mobility and aggression will face more painful and cruel responses," the IRGC said in a statement conveyed by Iran's Tasnim news agency.

This comes as no surprise.

Since the supreme leader has publicly vowed severe retaliation, the Iranian system had no choice but to act. If Iran had done nothing after all the loud threats of revenge, particularly by commanders of the IRGC, for the assassination of a general who reshaped the Middle East power balance in Iran’s favour, the system would have appeared weak and humiliated.

But for Iran, the issue of retaliation was not just a matter of saving face. Not responding to such a devastating strike could embolden the US to take more aggressive actions.

'Strategic revenge'

Against this backdrop, the question of how Iran would respond was looming over the region and the world in the days following the assassination. The attack in the early hours of Wednesday on US military bases in Iraq may be just the beginning.

IRGC commander Hossein Salami has suggested that revenge of a “strategic” nature, both geographically and over time, would have a definitive impact.

Tasnim News Agency, the IRGC’s mouthpiece, recently presented five characteristics of this “strategic revenge” against the US.

Firstly, it noted that retaliation would not comprise a single act, but rather a chain of actions: “Some may think a strike on a US base would be complete retaliation, but this is not accurate.” Recompense for the death of Soleimani, described as Iran’s “second-most powerful figure”, cannot be defined “within the framework of a limited military operation”, the article noted.

Rhetoric aside, Khamenei has never in practical terms taken any steps to jeopardise the survival of the system by triggering a military conflict with the US or Israel

Secondly, Tasnim contended that since Soleimani was an international figure popular among the Axis of Resistance nations - including Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine - revenge would not be geographically limited.

Thirdly, the outcome of the revenge should be strategic, not tactical, the article noted. “The numerous retaliatory operations and heavy strikes on US assets should lead to strategic outcomes. One of these outcomes could be expelling the US from Iraq and the region.”

Fourthly, the retaliators would be numerous and extra-national. Tasnim noted that Soleimani played a major role in strengthening “resistance” groups, adding: “Those groups who gained political, military, and relative geopolitical advantage [over the US and Israel], including Yemen’s Houthis, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Palestine’s Hamas and Islamic Jihad, Iraq’s Badr army and Shia militias, and Afghanistan’s Shia … can jeopardise the interests of the US and Zionists during the process of retaliation.”

Tasnim added that the US could not accuse Iran of being complicit in these groups’ actions, as they are independent actors.

Finally, the article noted that while retaliation would be partly formal, on behalf of the government, there could also be independent retaliators who may even strike “military interests of the US on its soil”.

Measured response

During Soleimani’s massive funeral on 6 January, the crowd chanted: “Khamenei, revenge, revenge.” Will what Tasnim outlines, what Salami described in his compressed statement, and what Khamenei has referred to as “harsh revenge”, actually take place?

Over the last three decades, with Iran under the leadership of Khamenei, there have been numerous escalations of conflict between Iran on one side, and the US and Israel on the other. Yet, rhetoric aside, Khamenei has never in practical terms taken any steps to jeopardise the survival of the system by triggering a military conflict with the US or Israel.

On 5 January, Iran said it would roll back its commitments under the 2015 nuclear deal. Interestingly, it did not withdraw from the agreement and vowed to continue cooperating with the UN’s nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Tehran also said it was ready to return to its commitments once it again enjoyed the benefits of the agreement.

This development is worthy of note because it shows that, while tensions between Iran and the US have escalated to one of the highest levels since the inception of the Islamic Republic - maybe only comparable to when the US downed an Iranian passenger plane in 1988 during the Iran-Iraq War - Iran has taken a measured step. It has kept the door open for future compromise and did not abandon the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, as some Iran observers had expected.

Following the Iranian strikes, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said in a tweeted statement that “Iran took and concluded proportionate measures in self-defense", adding that: "We do not seek escalation or war, but will defend ourselves against any aggression."

Shock therapy

All that said, Iran faces a much bigger problem than revenge over Soleimani’s killing. Because of Iran’s inability to sell oil due to US sanctions, the very survival of its governing system is in jeopardy.

The 2017 and 2019 uprisings were unprecedented: never in the previous four decades had two uprisings of this scale happened in such a short time span. And for the first time since the 1995 riots, the poor took centre stage.

On 25 November, in a report to the Iranian parliament, the Ministry of Intelligence said that most of those arrested “were unemployed or low-income”. What the system has always worried about - the formation of a “movement of the hungry” - is gaining momentum.

To understand the magnitude of the stalemate that the Iranian system faces, the November remarks by Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, are of worthy of note: “We are in the toughest days since the revolution.” He added that the government could not identify the revenue to meet a significant portion of next year’s budget.

So, while revenge could be a factor, using this opportunity to escape from its current threatening predicament is of much higher priority for the Iranian government.

Retaliation, contrary to suggestions from the IRGC, will probably be calculated and limited, perhaps aiming to cause a Middle East oil shock that forces the international community, particularly Europe and China, to scramble to work out a deal to let Iran sell its oil.

The Gulf could be the theatre of choice for a limited war. Iran’s economy needs shock therapy to push back against the US, but there is always the risk that things could spiral into an all-out war.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].