Power shortages, warnings of internet cuts place further strains on Lebanon

Overlooking Martyrs’ Square and downtown Beirut, the working-class neighbourhood of Khandak al-Ghamik appears to be hidden in the shadows, with its darkened windows bearing witness to yet another electricity cut.

Nearby, the upscale Saifi neighbourhood is brightly lit, with some remaining Christmas ornaments visible on the balconies of its luxury apartment buildings and shops.

Lebanon’s new year has kicked off with a series of worsening power outages, exacerbating an already tense economic and political situation for the country more than three months into a large-scale protest movement.

'The voices of a whole nation... are being thrown into the void'

- Joe Nassar, student activist

Meanwhile panic ensued following an interview with Imad Kreidieh, the head of the state-run telecom operator Ogero, earlier this week, in which he warned that the country’s already fragile access to the internet could possibly be jeopardised by the ongoing economic crisis.

Joe Nassar, a student activist, said the news of a potential internet and electricity blackout felt like a slap in the face to protesters who continue to demand better infrastructure and social services.

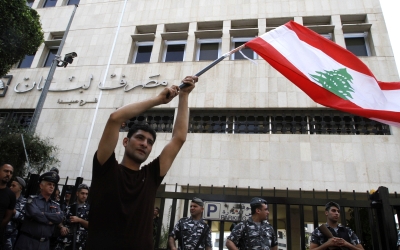

“The voices of a whole nation... are being thrown into the void,” Nassar told Middle East Eye while protesting at the Central Bank on Beirut's Hamra Street on Thursday. “We’re being ignored, and that’s outrageous.”

Left in the dark

Beirut’s daily power cuts have recently surged, with hours differing depending on the neighbourhood. But even households that can afford the most common coping method for cuts - external generators - have had to shell out more money in these circumstances.

“It’s far worse here in Tripoli,” Jihad Makki, a Lebanese social worker and resident of the northern Lebanese city, told MEE. “Especially in marginalised areas… we’re seeing power outages of up to 18 hours a day.”

Even prior to the country’s economic crisis, which became one of the sparks triggering a massive national uprising since October, power cuts have been an integral part of people’s daily lives since the country entered a 15-year civil war in 1975. Those who can afford it cope by paying informal generator providers.

And not all power cuts are alike; Beirut’s daily power outages usually last three hours, but other areas of the country have to survive with longer cuts.

“Some areas like Abou Samra [in Tripoli] face 24-hour outages [on] some days,” Makki added. “[Even] in [higher-end] residential areas… power cuts on average lasted eight to 12 hours daily.”

The heightened power cuts have proven to be an economic burden, with households having to pay more money for external generators or falling back on battery-powered lights and gas heaters.

The winter season has furthered compounded the issue, particularly in marginalised and low-income areas.

In schools and hospitals, the increased power cuts also compromise their ability to operate at full capacity.

But why have power cuts got worse? Lebanon’s national currency, the lira (LBP), pegged to the US dollar, has inflated remarkably since October.

Dollar shortages have significantly worsened since banks set limits on cash withdrawals at banks, and angry confrontations between customers and bankers have prompted intermittent bank closures.

Though the Lebanese lira is officially pegged at 1,507 to the dollar, black market exchange rates have dominated the Lebanese market in recent months. Over the past month, that number has gone up to over 2,000 LBP.

In light of these troubling developments, ministers, who since Saad Hariri’s resignation as prime minister on 29 October only operate in a “caretaker” capacity, have tried to quell the situation.

The state-subsidised Electricite du Liban (EdL) power company was quick to sound the alarm, saying that the government has delayed subsidies, possibly pushing EdL to reduce daily electricity more systematically.

Caretaker Energy Minister Nada Boustani denied earlier this month that there were fuel shortages, adding that daily distributions were sustainable for electricity generation until February.

However after February the 2020 state budget, which would include credit lines, would need to be ratified for electricity generation to continue for the remainder of the year, she warned.

The energy minister did not respond to MEE’s request for comment.

Risk of internet cuts

With the country facing a worsened electricity crisis, the prospect of an internet shutdown is yet another alarming indicator in an already grim forecast for Lebanon.

“Until now… we are able to handle things through the Central Bank, but we don’t know about the coming months,” Ogero’s Kreidieh told Al-Jadeed television on Sunday, adding, “No one could clarify what lies ahead for us.”

He warned that shortages in US dollars could be mean quarterly costs necessary to keep Lebanon’s internet up and running may not be paid on time.

'Sadly, in Lebanon, we wait for the problem to happen before handling it'

- Karim Rifai, Ogero spokesperson

According to Lebanese Center for Policy Studies researcher Sami Zoughaib, mismanagement of public funds in Lebanon - like its daily power cuts - is not a novelty.

“Mismanagement of public funds is a characteristic of the Lebanese government’s spending behaviour,” Zoughaib told MEE, citing the Ministry of Telecommunications’ whopping $75m investment in a new building last summer.

“However, the recent problem with [US dollar] liquidity exacerbated this problem.”

Even before rumours swirled of an impending internet blackout in Lebanon, protesters feared state-enforced internet blackouts such as those imposed following uprisings elsewhere in the Middle East.

“We were scared of such a situation, especially when we would gather in crowded areas,” young activist Farah Baba told MEE. “We would panic whenever the 3G [signal] was weak and we couldn’t contact someone.”

Ogero spokesperson Karim Rifai told MEE that in light of the country’s ongoing crisis, it was never Kreidieh’s intention to instil fear or panic.

“[This is the] same problem faced by many major sectors,” he told MEE. “We need to assess things… you know there is a crisis when it comes to transferring dollars.”

Rifai added that Kreidieh intended to approach the situation “positively and proactively,” rather than with panic and fear.

“Sadly, in Lebanon, we wait for the problem to happen before handling it,” said Rifai, reiterating that there should be nothing to worry about.

Which way out?

Lebanon’s 2020 budget is lingering in parliament, which has not convened yet this year but is set to meet towards the end of the month. In the absence of a budget, the prospect of electricity cuts grows ever more likely.

In any case, Zoughaib is not confident that ratifying the 2020 budget would be the solution to the power crisis. With Lebanon trying to implement austerity measures on most ministries, routine electricity coverage could end up diminishing either way.

“Spending on electricity… is set to be capped at 1,500bn LBP [$995,025], down from 2,500bn LBP [$1.6m] in 2019,” he said, adding that this alone would weaken capacity to provide power to the country’s inhabitants.

“The extent of this is reliant on the prices of fuel in 2020.”

How do these developments translate on Lebanese streets? With protests in recent days heating up with renewed roadblocks, riots, and large-scale arrests, some have insinuated that this adds fuel to the fire.

“I think this is only going to feed into the simmering situation,” Beirut-based Middle East researcher Bachar El-Halabi told MEE, adding that the root causes of these problems have yet to be addressed.

With a new cabinet not yet formed amid increased “tensions between the political elite”, Halabi expects that a new cabinet will try to appeal for aid packages before trying to address and take on internal issues that have angered demonstrators.

“It’s probably going to try to negotiate with international organisations, such as the World Bank and IMF… rather than go towards starting to implement solutions or reforms” internally, Halabi predicted - adding that the most effective solution would be internal reform and independent and transparent legal action.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].