Continuing Egypt's revolution from exile: Ramy Essam and Ganzeer

Nine years on, and rock artist Ramy Essam, dubbed the voice of Egypt's revolution, remains as defiant as ever.

"I'm trying to remind the authorities that the more they put us in jail the more there will be more of us," he says, as he catches his breath between songs in which his voice roars above a wall of sound made up of heavy metal guitar riffs.

Tracks like Erhal (leave) and Tatti Tatti (bow your head), performed in front of tens of thousands in Tahrir Square in 2011, provided the soundtrack for Egypt's revolution, which has since descended into dictatorship and profound disappointment.

But speaking to Middle East Eye after performing to a packed audience marking the ninth anniversary of the start of revolution, Essam is upbeat.

'I can understand that people inside Egypt might lose hope, because it's very tough there'

- Ramy Essam

"Yes, the situation now is very dark, it's very tough," he said at the event in Brooklyn titled Tahrir and Beyond.

"But young people are always sending me messages talking about a better Egypt and talking about freedom. I never had the chance to talk about these things even when I was 20 or 21. This is the generation that saw us doing the revolution and they were so inspired.

"We planted seeds in the young generations, and nobody can stop these seeds from growing."

Essam, who defines himself as an artist and not an activist, despite the political content of his music, said that 2011 also marked the start of an artistic revolution in Egypt in which oppositional art became normalised.

However, a vicious clamp down on freedom of expression since Abdel Fattah al-Sisi's military coup in 2013 has seen many of the revolution's artists flee into exile.

After being arrested and torture, Essam was forced to leave in late 2014, taking up refuge in Sweden. Yet his hope remains undimmed.

"I was lucky to be outside Egypt for five years because I can still see hope. I can understand that people inside Egypt might lose hope because it's very tough there."

Ganzeer, the 37-year-old street artist who also shot to fame in 2011, described the revolution as "the most spiritual experience I’ve ever had."

He vividly recalls the moment on 25 January 2011, the first day of the revolution, when he saw a civilian man clamber onto the back of an armoured vehicle, disarm a soldier who had been shooting at a crowd of protestors and lay into him.

"It was the first time where I saw people who did not know each other really forget entirely their ego and do crazy things which they've never done before," he told MEE, after presenting some of his revolutionary art at the event.

Currently living in exile in Houston, Texas, Ganzeer says that exile has given him and Ramy the freedom and the privilege to keep Egypt’s artistic revolution alive.

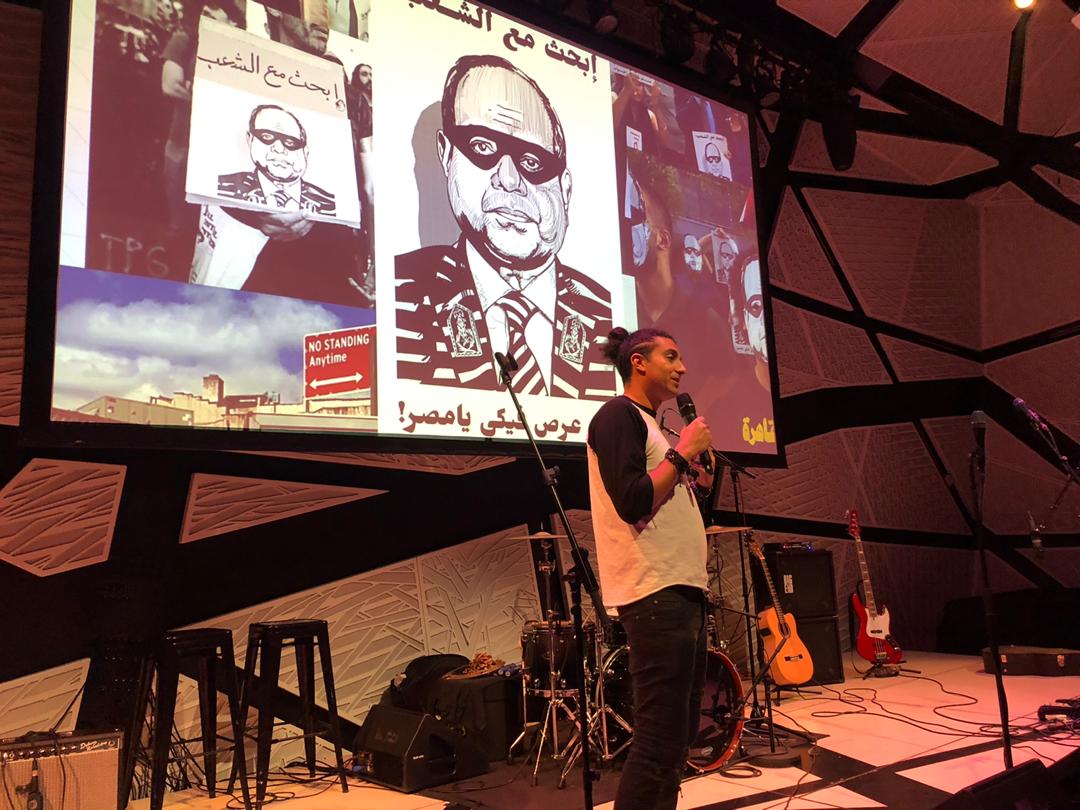

In September, Ganzeer drew the image that would come to define a new wave of protests against the sitting president, triggered by corruption allegations from former military contractor Mohamed Ali.

The illustration of Sisi dressed in a striped jacket and tie, but drawn as a cartoonish cat burglar, quickly went viral.

"I could have said there's no role for me to play in exile and ignored the whole thing. Just creating that image and making it available played a role."

Ganzeer also points out that The Age of the Pimp, a song Ramy wrote while in exile, has been played by protestors on the frontlines of demonstrations in Beirut.

"Lebanese protesters connected with it. They feel like they are living in the age of the pimp where the government is just selling the country out," he said.

He credits protestors themselves for taking risks.

'I could have said there's no role for me to play in exile and ignored the whole thing. Just creating that image and making it available played a role'

- Ganzeer

"At the end of the day it's not just the people in exile acting alone," he said. "People in Lebanon decided to take Ramy's song and play it and others in Egypt decided to print the image and paste it all over the city."

"It's a group effort between us and them. The more everyone plays the role they can best play, the more we have a chance of getting rid of these people."

Songs such as Letter to the United Nations Security Council, which imagines a group of illiterate and disadvantaged Egyptians writing to the international community for having betrayed the revolution, show a more tender side to Ramy's music.

A far cry from the body thrusts and audacious leaps that dominate the set, he appears standing alone, holding just a guitar, his band having melted away into the background.

Referring to Sisi's recent visits to Washington and London, he says it's not just Egyptians living in exile who have a duty to stand up to the regime.

"I would love to see a big riot in London streets when he's there, where people say we don't want this killer in our country."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].