The West's curious obsession with the veil

In the aftermath of the assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani, US President Donald Trump retweeted a fake image of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer wearing Islamic headwear, with the caption: “The corrupted Dems trying their best to come to the Ayatollah’s rescue #NancyPelosiFakeNews.”

The targeting of Pelosi, who was at the forefront of procedures to impeach the president, by associating her with a powerful and emotionally charged symbol of “difference” - the veil - fuels Trump’s accusations that Democrats are too accommodating of “foreigners” at the expense of white Americans. This narrative associates the Islamic veil with deception, security threats, betrayal and corruption.

Fantasy of unveiling

In 2017, Trump reportedly had a change of heart about his decision to withdraw from Afghanistan after being shown an image by National Security Adviser HR McMaster of Afghan women from 1972, unveiled and wearing short skirts, in an effort to demonstrate that the campaign was not hopeless as Trump believed, but a cause worth fighting for.

Trump was not alone in being converted by this singular image of undisputed freedom, which reignited the fantasy around unveiling. Versions of it have made the rounds on social media, posted by individuals and human rights groups, framing complex historical, political and economic realities in “before and after” snapshots laden with sweeping judgements.

No truth about Muslim women's lives, aspirations and achievements has troubled prevailing beliefs about Muslim women

Once upon a time in Afghanistan, we are told, Afghan women who looked like us strolled the country’s cities, now abandoned to the wasteful carnage of fundamentalism, which swallowed up women’s bodies in a horrifying disappearing act. The Islamic veil conspires to repress all hopes for freedom.

What is it about the veil that can produce such contradictory readings of danger and endangerment, to declare geopolitical allegiances and radically alter foreign policy agendas? What is it about the veil that allows for the weaponisation of multiculturalism, immigration, citizenship, terrorism, women’s rights and human rights?

These are the questions that encircle Muslims and trigger a crisis over western identity and values. As with Trump’s border wall, only on the other side of the veil - the unveiled - can one avoid contamination. In my book, The Political Psychology of the Veil: The Impossible Body, I trace this interrogation of who Muslims are and what they want from “us” through the recurring question of the veil.

Making sense of an obsession

Though this book is certainly not the first to be written on the topic, nor will it be the last, I wanted not to look beneath the veil to find out the “truth” about Muslim women, but rather to examine the veil’s excessive presence in the western imagination, and to make sense of this obsession.

The veil’s recurrence in whatever form - hijab, chador, niqab, burqa - despite historical, anthropological and activist-driven responses to deconstruct the western preoccupation with Muslim women and their bodies, points to an obsession that cannot be satisfied.

Facing growing hostility during the 2000s after 9/11, Muslims in the West, and Muslim women in particular, attempted to counteract the circulation of problematic imagery of Islam by shedding light on more humanising stories and experiences.

Before Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram enabled wider platforms for these voices, websites such as Muslimah Media Watch, AltMuslimah and others refreshingly challenged representations of Muslim women as embodiments of Islam’s oppressive demands.

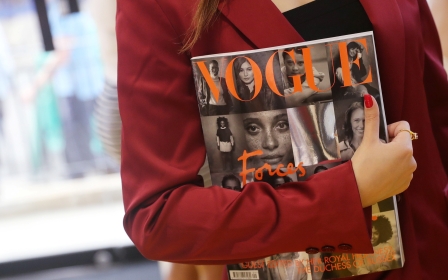

Since then, we’ve seen an explosion in Muslim women’s activism, as part of a type of storytelling that speaks back, dispelling, challenging and breaking stereotypes by revealing experiences of empowering individualism. At a time when Muslim women have never been so visible - from modest fashion, to sports, to politics, to business and entertainment - the recurring imagery of the veil as a coercive “other” remains curious.

Persistent presence

The veil continues to be summoned to alarm or inspire freedom for western audiences. No truth about Muslim women’s lives, aspirations and achievements has troubled prevailing beliefs about Muslim women.

The notion of “lifting the veil” to show who these women really are, equates the veil with constraint, suppression of the self, and resistance to modernity. In the humanising stories about Muslim women’s lives, there is a desire to escape the veil by looking beneath it - to uncover a truth beyond it, where Muslim women confess love for Maroon 5, demonstrate rap skills, skateboard and do ballet.

My book turns a critical gaze on the psychic and political investment in visibility - the visibility of Muslim difference and of the body - and explores what that actually looks like in the Muslim context, where visibility is problematised and entangled in Islamophobic fear and anxiety.

The veil’s persistent presence in the western imagination can be explained as a visible difference - a sign of Islam’s growing presence in the West - that invokes expressions of hostility, such as calls to ban the veil or attacks on Muslim women by members of the public.

Yet, I argue that the fixation on the veil is much more than a marker of stubborn cultural differences, portending something deeper about what its removal promises. It centres on a more destabilising question: what is it about the body, as veiled and unveiled flesh, that burdens it with civilisational value, marking the boundaries of freedom and constraint?

A critical gaze

Tracing the veil through images and imaginings of Muslim women in secular liberal projects of humanitarianism, feminism and Islamophobia encourages us to think more deeply about the beliefs that uphold our moral universe, and the conditions through which we arrive at freedom, knowledge, truth, and bodily integrity - all universal impulses that can lead to destructive ends.

In anxious times, when our gaze can be so consumed with “others” - who they are, what they want from us and what they can do to us - that accusations, walls and bans are the only antidote, turning a critical gaze on these paranoid attachments is essential to extending the social and political imagination, making space for empathetic thinking.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].