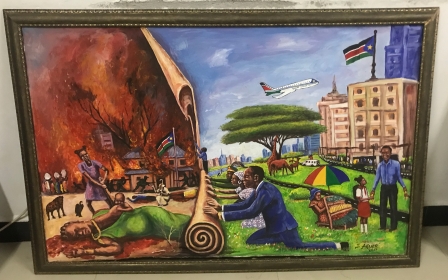

Is Sudan turning a page on its troubled history?

Ever since independence in 1956, Sudan has been the source of many of Africa’s worst problems.

The long-lived insurgency in what is now South Sudan drew in neighbouring countries. Osama bin Laden made Sudan his home in the 1990s. The desire for power and wealth of Omar al-Bashir's regime ravaged the country for decades. It saw Khartoum wage a series of small wars against tribal groups on the periphery of the Sudanese state - most notoriously, the Darfur genocide, which claimed 300,000 lives.

It’s too early to be certain, but something seems to have changed for the better.

Providing solutions

Rather than creating problems, Sudan is providing solutions.

With the support of Khartoum, all of the regional powers have been brought together in South Sudan's capital, Juba, for a series of peace negotiations. At the centre were efforts to form a new unity government in South Sudan and end years of civil war between President Salva Kiir and former Vice President Riek Machar. After months of talks, this week they finally agreed a deal.

For decades, Sudan has helped sow division in that country. They first backed Machar in a coup against rebel leader John Garang in 1991 and supported him when he broke out in 2013.

But in recent months, Khartoum has been central to ensuring Machar and Kiir reached an agreement, by providing security for Machar and applying pressure on both parties at tricky moments where talks appeared to be breaking down.

It was Sudan (acting along with Uganda) who broke the impasse in the summer of 2018 by collapsing the talk into a straightforward discussion between Machar and Kiir. This move upset certain stakeholders, but provided a necessary new dynamic.

At the same time, Sudan is engaging in separate peace talks with its own rebel groups.

Last month, Sudan opened the way to end the long-running insurgencies in the Blue Nile and South Kordofan states by signing a provisional peace agreement with a rebel group.

Further afield, Sudan is forming stronger ties with European powers by helping to stop migrant flows into Libya.

It is important not to be overconfident. There are fears that a fresh military coup is brewing in Khartoum

Most eye-catchingly of all, Sudanese government delegations travelled to Darfur in early January to show support for the Massalit tribe, which had been attacked by Arab groups.

Over the last few months, Khartoum has been at the epicentre of an astonishing regional transformation. The biggest factor is the departure of former president Omar al-Bashir, who led a military coup in 1989 and a brutal regime for three decades.

Early last year, Bashir was ousted by the military, which claimed to act on behalf of the people of Sudan. The new provisional government recently suggested it was ready to hand over Bashir to the International Criminal Court (ICC), a move that would play a symbolic role in ending Sudan’s status as a pariah state.

The role of Hemeti

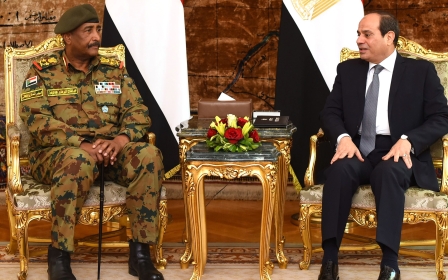

Remarkably, the most dynamic figure in the new dispensation in Khartoum is Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo, commonly known by his nickname Hemeti. It’s said in Khartoum that Hemeti - and not Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who chairs the transitional military council - is calling the shots.

When I reported on the Darfur atrocities 14 years ago, Hemeti was one of the Janjaweed leaders responsible for much of the violence against local tribes. His role as commander of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has seen him carry out attacks on rebels throughout Sudan, as well as protestors in Khartoum.

Hemeti, however, is not one of the Sudanese chiefs wanted by the ICC for war crimes. Minni Minnawi, one of the Darfuri leaders involved in peace talks, was careful not to blame Hemeti for the violence to his people when I met him in Juba last month: “Hemeti was the tool. Bashir was the mastermind.”

Hemeti is now leading negotiations with rebel leaders that could bring an end to conflicts in which he played such a brutal role. There is no doubt that he has emerged as a peacemaker in recent months: parallel negotiations between bitter rivals Kiir and Machar are also dependent on Hemeti.

Machar, who is based in Khartoum, only travels to Juba in the company of Hemeti and his security forces. You can tell when the pair are in the city by the trucks full of Kiir’s elite presidential guards stationed outside their hotel.

Power struggle

It was Hemeti who signed the first peace deal with a faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North, a rebel group based in Blue Nile state that has been in conflict with Sudan since 2011.

Hemeti has by no means turned into a saint. Last summer, his RSF forces killed more than 100 protesters in Khartoum, wounding hundreds more. Critics accuse him of trying to launder his reputation.

Bashir is gone and there has been a radical change in the power structure of Sudan. However, it is important not to be overconfident. Elements of the old administration remain, and there are fears that a fresh military coup is brewing in Khartoum.

Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, a former UN official, was not even consulted by the army before the recent meeting between Abdel Fattah al-Burhan with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Similarly, previous peace agreements have also come to nothing. The Darfur peace agreements of 2006 and 2011 both collapsed. A great deal of further work is needed to make sure any agreements hold this time around.

But history shows that men with blood on their hands can become peacemakers, and I believe tectonic shifts are taking place. If progress persists - and there is every reason to expect that it will - 2020 could be the most hopeful year in Sudan’s long and troubled history.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].