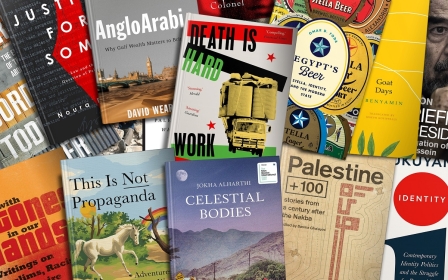

Egyptian cult classics: 11 books that are worth reading

By common definition, a cult film is either obscure or unpopular with mainstream audiences, yet beloved by a small “cult” following.

While literary cult classics generally don’t have the same public profile as cult films or comics, cult favourites do play an important role in the rejuvenation of literary culture.

A literary cult legend often emerges when an author dies young, perhaps by suicide, or else mysteriously disappears from the literary scene. Their writing would often have been out of step with the times: sometimes because they were too revolutionary, sometimes because they were too wickedly funny, or - in the case of Egyptian cult classics - they made too free a use of colloquial Egyptian Arabic.

But these cherished classics survive their initial shunning by mainstream audiences - in part because they’re excellent books, but also because their themes speak to contemporary audiences: cult favourites taken up by contemporary Egyptian audiences depict failed revolutions, sharp class differences, and deferred dreams.

As for which recent Egyptian titles might yet become cult classics, it’s hard to guess. Perhaps Youssef Rakha’s complex Book of the Sultan’s Seal will find its passionate cult audience. Perhaps Ahmed Naje and Ayman Zorkany’s Using Life, in part because of the jail time Naje served for a chapter of it.

Yet these classics of the future will also be determined by what future readers are looking for in our present, their past.

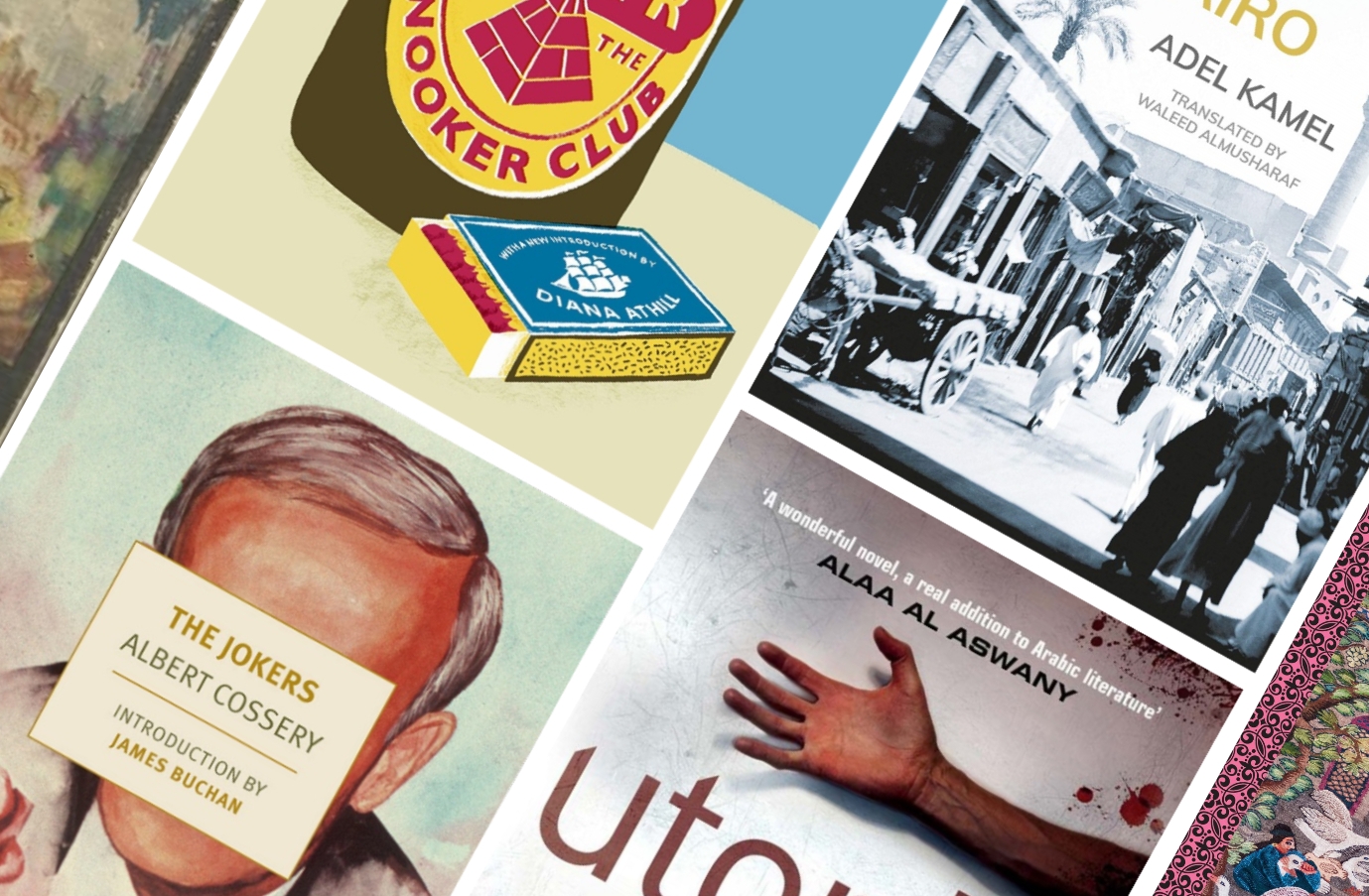

1. Beer in the Snooker Club

by Waguih Ghali

Waguih Ghali had some famous friends: acclaimed British author Diana Athill helped cement Ghali’s place in the literary pantheon with her book After a Funeral, written in the wake of Ghali’s suicide.

Ghali, who wrote in English, was also fortunate in his translators: the great Egyptian poet Iman Mersal and translator Reem al-Rayyes brought Beer in the Snooker Club to Arabic in 1964.

Also that year, a collection of Ghali’s short stories appeared in Arabic. Although the original English stories were published in The Guardian newspaper in the 1950s and 1960s, they have never yet appeared in book form in English.

Beer in the Snooker Club follows the protagonist Ram in two time periods, in the moment of the 1956 Suez crisis and later, when he has become disillusioned with then-Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Although power had changed hands, to Ram's mind life for Egypt’s poor didn’t fundamentally change.

An echo of his creator who was born into Egypt’s Coptic upper class, the Francophone-educated, downwardly mobile Ram feels dislocated from all segments of Egyptian society.

Why read it now? For the scene where Ram pushes Mounir into the pool, the hilarious portrayal of the American fact-finding character “Jack,” and his reflections on how he and his Western-educated friends were ill-equipped to help run contemporary Egypt: “Font knows how to trim the cake, and frost it, and garnish it with the latest decorations, but he doesn’t know how to bake the cake.”

Ram’s friends will have to wait on Nasser to “bake” Egypt’s cake - or its political system.

2. The Magnificent Conman of Cairo

by Adel Kamel

Adel Kamel’s satiric Mallim al-Akbar (Mallim the Great) was rejected by the Arabic Language Academy in 1942, probably because of its directness and its humorous portrayal of what was then contemporary Egyptian life, particularly Egyptian bureaucracy and government ministries.

The author did go on to publish his novel, but felt ignored by the literary establishment and stopped publishing entirely in the mid-40s. Still, Naguib Mahfouz never forgot how much he admired his friend Adel Kamel’s work, and Mahfouz wrote an essay about him when he left Egypt for the US in the 1990s.

Although Kamel’s two novels were out of print for more than half a century, they were brought back by Egyptian publishing house Dar Karma in 2014.

According to Dar Karma publisher Seif Salmawy, Mallim the Great “had long been out of print, and many people had heard of it, but very few had actually read it,” - although that soon changed in 2014.

This month, the novel appears in English in Waleed Almusharraf’s translation, with a new title: The Magnificent Conman of Cairo.

Conman revolves around two characters: Khaled, the unhappy son of a pasha, and Mallim, a would-be carpenter and son of a conman.

Why read it now? Fast-paced and funny, this novel illuminates Egypt’s class divides, how hard it is to “do right,” and who the government serves.

3. The Romanticisms

by Safynaz Kazem

The Romanticisms (1970) is a biting, funny, and philosophical travel memoir by the fearless Egyptian critic and journalist Kazem, who was pushed out of the literary and journalism establishment for her sharp tongue and sharper critiques.

Her embrace of Islamist politics caused many in the literary community to turn their backs on her work. Yet this memoir, which is set during Kazem’s time in the United States, is told in a forthright, blisteringly funny tone.

It also comes recommended by poet Iman Mersal, a champion of neglected women’s voices. An excerpt is available in English translation by Hadil Ghoneim.

Why read it now? Safy is by turns philosophical, ridiculous, and hilarious, and her observations of the US in the mid-20th-century are still vividly trenchant.

4. Utopia

by Ahmed Khaled Towfik

This novel breaks our rules a little, as Ahmed Khaled Towfik (1962-2018) had many fans during his lifetime.

However, his popular genre novels were also sniffed at by the literary establishment, and he never won the big prizes one might expect for a writer of his status.

There is also a definite Towfik cult; many eagerly (and anxiously) await the Paranormal series, based on this title, currently being adapted to a Netflix series from his novels.

Utopia (2008) depicts a near-future landscape in which wealthy Egyptians live in compounds that are protected by US soldiers. In the novel, two pampered characters break out of the compound against their protectors’ advice to kill and bring back one of the impoverished beyond their walls.

The novel is available in Chip Rosetti's English translation.

Why read it now? This fast-paced SF thriller imagines a brutal near future that has echoes of Egypt 2020.

5. The Jokers

6. A Splendid Conspiracy

both by Albert Cossery

Albert Cossery (1913-2008) was an Egyptian-born French writer of Syrian origin. He wrote highly comic critiques of both the tyrannies and the creed of capitalist productivity of the 20th century. Throughout his eight novels, laziness was elevated to a virtue of the highest order.

In The Jokers (1964), translated by Anna Moschovakis, which emerged from the same social milieu as Beer in the Snooker Club, revolutionaries undermine the government with over-the-top pranks.

In A Splendid Conspiracy (1975), translated by Alyson Waters, the central character Teymour returns to Egypt from Paris with a fake degree and gets into all sorts of trouble - not unlike Khaled in Mallim al-Akbar.

All but one of Cossery’s novels have been translated into English, where he has an underground following among the anti-ambitious who are attempting to throw aside the social ladder.

Why read it now? We’re still fighting power and productivity doctrines, and laziness and jokery remain two key weapons in our (collective) quivers.

7. The Stillborn

by Arwa Saleh

Occasionally, translation can fire interest in an original, and news of Samah Selim’s translation of The Stillborn (1997) sparked a re-issue of the Arabic, also from Egypt's “Family Library” series.

Leftist activist, theorist, and student-movement icon Arwa Saleh killed herself in 1997, the same year her Stillborn: Notebooks of a Woman from the Student Movement Generation in Egypt was published.

The memories of her suicide still ripple through contemporary Egyptian literature. As Selim writes in her introduction, “Both the woman and her razor-sharp critique of her generation of intellectuals and militants remained a constant, subterranean presence in the political imagination and the recriminations, polemics and debates of those twenty intervening years.”

Saleh’s book ranges from political science to philosophy to gender critique, as here, where she remembers her time in Spain: “I used to walk for hours, and talk to myself the whole time. The world I observed around me was so much more human than what I’d been used to back home. Gardens and public love…long walks down lighthearted streets where teenagers exchange kisses without fear.”

Why read it now? Like many of the books listed here, it offers a look at why the people depicted “failed” to change Egypt. In so doing, Saleh offers many sharp critiques and suggestions that still ring true.

8. Memoirs of an Overseas Student

by Lewis Awad

Lewis Awad (1915-1990), a writer and critic from the Upper Egyptian city of Minya, was a student at Cambridge between 1937 and 1940. His Diaries of an Overseas Student (1965) is a sharply observed, often funny memoir of that time, as well as of his sea journeys there and back.

Critic MF Kalfat writes that: “Awad’s manuscript was rejected by the state censors in the 1940s, then his own copy was lost shortly after that, and the book would have never seen the light were it not for a series of serendipities.”

It took 20 years to get Memoirs published. One of the reasons it was so controversial was its use of an Egyptian colloquial Arabic that much of the literary establishment considered too vulgar for “proper” literary work.

Kalfat adds that: “Even reading it now, a sense of loss remains: whether it might have changed literary history had it appeared closer to the time of its writing.”

An excerpt is available in translation, by Nariman Youssef.

Why read it now? For what it tells us about the relationship between Brits and Egyptians, as when Awad notes: “There are small things you could do to make others feel you were better than them. Without really saying anything. Things that anyone could do. Like when someone asks you the time, you give him a grumpy look. He’d understand and not ask again.” Also, for its occasionally startling language and frequent humour.

9. Brains Confounded by the Ode of Abu Shaduf Expounded

by Yusuf al-Shirbini

The satiric, earthy, and vituperative Brains Confounded (translated by Humphrey Davies) is not a novel, but is instead a parody of the verse-and-commentary genre that was popular in the author’s day, writing in 17th century Egypt.

It paints a sharp portrait of Egyptian villagers: particularly peasant farmers, “men of religion,” and rural dervishes. It’s hard to know exactly what sort of reception al-Shirbini’s work got in its time, since we have no bestseller lists from the 17th century.

But the author seemingly never attracted the attention of his contemporaries, complaining “who cannot pen a line is blessed with a living fine, while the master of wit sees of victuals not a whit[.]”

Yet this book has long had its passionate Egyptian adherents: both for its bawdy depictions of village life and for its language, which moves deftly between colloquial and “high” classical expressions.

Translator Humphrey Davies has named it as one of his favourites, and novelist Youssef Rakha wrote a passionate introduction to a 2019 paperback edition.

References to Brains Confounded also appear in contemporary Egyptian literature, as in Abdel Rasheed Mahmoudi’s After Coffee (translated by Nashwa Gowanlock).

Why read it now? First, for the humour. But also for the connections between the Egypt of the 17th century and today.

10. Love and Silence

by Enayat al-Zayyat

Enayat al-Zayyat's little-known 1967 novel was thrust into the spotlight when, late last year, Iman Mersal's latest book came out: In the Footsteps of Enayat al-Zayyat. Mersal's publisher, Egypt-based Kotob Khan, also re-issued Love and Silence.

It was 1993 when Iman Mersal stumbled across Enayat al-Zayyat’s novel at the Sur Azbikaya book market, and, from then, it turned into an obsession with al-Zayyat’s life and work.

In Love and Silence, an 18-year-old woman falls into a depression after her brother dies, since her family cared only for him. Slowly, her confidence develops, and the novel ends with her enrolling in the College of Fine Arts and the Free Officers Movement of July 1952.

Why read it now? Iman Mersal is right: It's time for us to excavate and engage the excellent women's writing from 20th century Cairo, and across the region, that went unnoticed.

11. Qantara the Unbeliever

by Mustafa Musharafa

Publishers rejected Musharafa’s novel - also written in Egyptian colloquial Arabic - in the 1920s. Spurned, the author spent a long time in England, studying and teaching English literature and marrying an Englishwoman. But, in the end, he returned to Cairo, finally publishing his novel in 1966.

Qantara the Unbeliever follows a man named Sheikh Abdel-Salam Qantara, who stops believing in the 1919 Revolution, leaves Egypt, but eventually returns.

This classic novel was written entirely in Egyptian colloquial Arabic, and it had fans like Yusuf Idris and Ibrahim Aslan. But it also had its detractors, who felt colloquial wasn’t “appropriate” to “serious literature,” and it long disappeared from print.

Yet it retained its legendary status, and it was finally re-issued under the Egyptian government’s “Family Library” imprint in 2012. It is not yet available in English.

Why read it now? Ibrahim Aslan said of the vibrant, straightforward novel: “Had it been known at the time and distributed widely... then the face of writing in Egypt would have been different.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].