How a movie star (and my mother) made me a feminist

When I think of my earliest role models, there is one who comes to mind time and again.

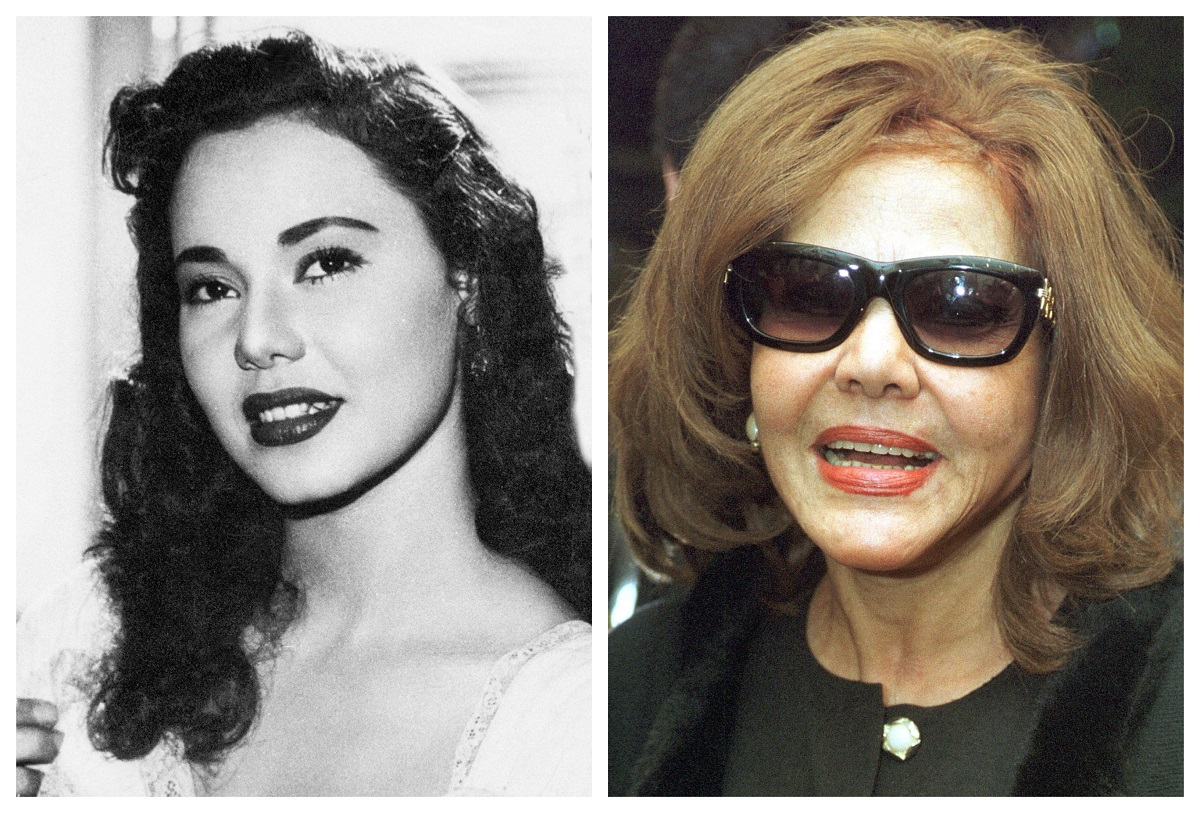

I only ever knew the Egyptian movie icon Magda al-Sabahy through her stage name: Magda. With her sultry looks and trademark husky voice, she came to fame through dozens of features during the 1950s and 60s (my mother used to say that I had cheekbones like Magda: flattering, although I don’t see it myself).

But there’s something more important that I hope I have in common with Magda, something I have acquired over the years: the values I felt she represented.

Magda al-Sabahy passed away in Cairo on 16 January, aged 88. Her death was widely covered in Arab media, honouring her lifetime of achievement. I was saddened by the news of her death, which instantly brought back memories of her films.

And then, a few days later, a bizarre event occurred which further underlined the connection. Vitaly Zdorovetskiy, a Russian-American YouTube star, posted a video of himself atop the Great Pyramid of Giza. The stunt, aimed at raising awareness of the Australian bush fires, earned him five days in jail.

What do these two events – the death of a movie star and a stunt by a social media influencer - have in common?

To me, everything.

Heat in Cairo

Back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, summer days in Cairo felt endless. Going out in the heat was not an option. There was little temptation in inhaling hot air, or letting my bare skin sizzle against the car seats after I’d inched my way in.

My hair would frizz like a lollipop regardless of whether we left our home: the only way to tame it would be to jump into yet another cold shower. To save money and energy, we weren’t allowed to keep the air conditioning on for long, so it was either shower or simmer.

But I was generally happy during those lazy school holidays. I’d lay sprawled out in a cotton T-shirt and shorts on our beige velvet sofa imprinted with clusters of chocolate brown buds, the electric fan locked in my direction.

Our old-school TV set was a source of non-stop black and white Egyptian films. The few local channels were enough to guarantee that if one feature ended, you could easily find another, never needing to break the chain of movie-watching for anything other than a toilet break or social commitments.

The films were so familiar that it didn’t matter if you had to pick up the plot-line halfway through. Sometimes my mother would join me, or my brother if he wasn’t sleeping off a late night out with friends. But with or without company, the hours I spent sprawled like a jellyfish were too many to count.

I obsessed over the classic comedies – but the one I ranked above all others was Magda’s 1968 feature Hawaa ‘ala al Tareeq (Eve on the Path), written and directed by Hussein Helmy.

There’s something so comforting about switching TV channels and finding your favourite movie on. It feels like a bear hug, or slipping on a comfortable pair of jeans. That’s how it was with Hawaa 'ala al Tareeq.

It opens with a long sigh, as Mona, Magda’s character, explains on the phone to a friend how she feels caged in her parents' home.

“Oh Hikmat, if you could feel the agony that I’m in,” Mona says. “Ever since I was 12 years old, until now. It’s as if I’m in a solitary prison. Does it make us infidels that we were born girls?”

Hikmat (Suheir Samy) is a stiff-backed female entrepreneur, who teaches typing to women through a small business she has set up in her own name - a feat considered rare in 1960s Egypt.

With Mona’s help, Hikmat is also setting up an association to defend women’s rights. We find out later from her younger sister Nashwa (Madiha Salim) that Hikmat was only driven to such extremes after she was jilted by a boyfriend for who she’d left college. Hikmat’s voice is the metronome that keeps the beat of the women’s cause.

Mona’s call prompts Hikmat to launch into a tirade about why the fight is no longer over: bear in mind that Hawaa ala al Tareeq was released in 1968, only two years after women in Egypt were granted the right to vote.

“And that’s why I keep saying that the rights we’ve taken are not enough. Of course not!” Hikmat declares. “It’s not just about education, jobs, elections.”

Then Hikmat delivers a line that, to me, sums up the ongoing global struggle for gender equality: “What’s important is that all the men in the world must change the way they see us. To treat us equally - but from their hearts, not by the rule of the law.”

A fire burns within Mona as she listens to her friend articulate all her years of compounded frustration. On cue, Mona’s brother storms into her bedroom, slamming the shutters – presumably to stop the neighbours hearing his sister, or – God forbid – what she’s saying to her friend. Then he demands she cook him breakfast.

Later Mona tries to prove that Egyptian women have earned nothing in real terms. Gathering a bunch of girlfriends, they hire bikes and cycle to the pyramids of Giza. They are pursued by the wolf-whistling and boggled eyes of male onlookers, culminating in a standoff.

At that point Salah, a chivalrous passerby – played by Roshdy Abaza, one of Egyptian cinema’s favourite heroes – single-handedly beats up the thugs. Magda watches the fight with barely contained glee, then puts on a cool demeanour.

She glares back at Salah after he reprimands the women for putting themselves in such an “unbecoming” situation. “We’re free,” Magda replies, trying desperately to keep her composure.

The inevitable happens: Salah asks Mona’s father for her hand in marriage but she refuses, in dedication to the women’s cause. She is persuaded only when her suitor reads up on feminist theory and convinces her they would be truly equal.

But before long, the gig is up. Salah tires of biting his tongue - like when he comes home and finds his beautiful wife covered in a dusting of grime because she was trying to fix the boiler. Salah has no desire to cook or clean: he ends up headbutting her when they argue and she runs back to her father’s house, which is no more welcoming. When her divorce appeal fails, a despairing Mona decides that only the grandest of gestures will make a difference.

She heads back to the pyramids.

Magda the pioneer

It's been more than 30 years since I first watched Hawaa ‘ala al Tareeq yet I still struggle to see Magda as separate from her character. The little I knew about her seemed to corroborate this vision of her as a strong, passionate woman with firm ideals who left a legacy of more than 60 films.

Born Afaf al-Sabahi in 1931, in Tanta, north of Cairo, Magda got her first break was when she was only 15. Despite initial family worries, she eventually went on to star in dozens of popular films, including her breakthrough alongside Ismail Yassin in El-Naseh in 1949.

Looking back to my childhood, I realise I longed to mimic what I felt was an ideal balance of femininity and feminist values

The parallels between the actress and the character in Hawaa ‘ala al Tareeq are evident. My mother pointed out that just as Hikmat sets up her own business, so Magda founded her own production company, Magda Films. Its repertoire included religious and historic epics such as Youssef Chahine’s Jamila The Algerian (1958), charting the life of the Algerian revolutionary, Jamila Bouhired, played by Magda herself.

I learnt that this petite, beautiful, talented woman could punch far above her weight. Looking back to my childhood, I realise I longed to mimic what I felt was an ideal balance of femininity and feminist values.

Later I would discover Magda had received international awards, and was elected president of the Egyptian Women in Film Association in 1995, just a few years after she retired from acting

Yet it took Magda’s death to remind me of something that had bothered me about my favourite film all these years.

'Ah... I forgot the matchbox'

We’re back at the climactic pyramid scene, as Mona begins her arduous ascent. Still devastated by her shattered dream, she gasps her way up the jagged rocks, strands of hair flailing in the hot summer wind.

But when she gets to the top is when I begin to lose faith. She sits back on a rock and unwraps a can of lighter fluid she has carried all the way up. She reaches into her pocket and realises her error. The image is so tragically comical that when my mother and I repeat her words to each other, “Ah... I forgot the matchbox”, I honestly don’t know if we are laughing or crying.

Why did my heroine, my great icon of femininity, do something so stupid and reckless as forgetting one of just two essential items for her planned action?

I would much prefer that she change her mind up on that summit than to do something so stereotypically “female” that reduces the message of the film into a well-rehearsed joke about women’s lack of sense.

What follows is barely recompense. Abaza circles the pyramids in a small plane, piloted by his friend and with Hikmat also squashed on board. He tosses down a walkie-talkie so he can tell Mona that he’s changed, and will divorce her if she really wants that. But that he loves her. Mona chooses to trust him, just as the authorities reach her and place her under arrest for contempt of the law.

Realistic? I will not venture to investigate: as a young girl I appreciated a happy ending, romance and all. But the feminist-bending plot-line has always enthralled me, fuelling my desire to understand what it is about Hawaa ‘ala al Tareeq that both attracts and irks me so much.

It was only when I saw the video of that YouTube star on the summit of Egypt’s largest pyramid that I remembered why Magda’s life – and now death – had so moved me.

Was Hawaa ‘ala al Tareeq deriding feminism, as in the earlier scene, when the women hit the heels off the backs of their shoes and a janitor peers in shaking his head? Or was it enacting feminism with such a high calibre cast of female actresses?

Movie for my mother

Hawaa ‘ala al Tareeq was not the only film tackling the thorny topic of women’s rights in 1960s Egypt – it just happened to be the one that struck a chord for me. But the real influence in my life, the quiet yet persistent inspiration who helped highlight the importance of this film and others in the same vein, is my mother.

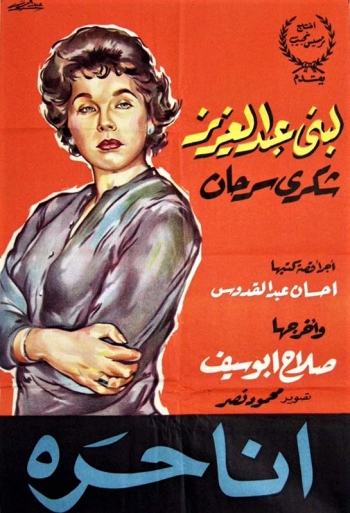

Driven by her own feminist ideals, she would often tell me about the film that she holds dear. Ana Horra (I’m Free), released in 1959, too boasts its own strong female Egyptian lead in Lobna Abdel Aziz: she plays Amina - coincidentally my mother’s namesake - a young woman desperate to escape the shackles of the home where she lives with her uncle and aunt. When pressured to meet a potential suitor, she interrogates him on his reading list, and later defends her choice to wear make-up.

Maybe the truth is that Magda and her missing matchbox have, to me, become a lament for my mother’s own losses. My mother aspired to an independence she could never achieve. But Ana Horra offered something she could at least hope for, stirring her to fight for an education that would eventually earn her not one but two bachelor's degrees.

Like many parents, she tried to salvage something from what she learnt about the value of freedom, and to plant this fervour in me. Over the years she sometimes faltered, as when she would join the choruses among our extended family, pleading for me to find a husband “before it’s too late”.

But she would always return with the stories, of how she admired the other Amina and what Ana Horra allowed her to see. Even now, decades on, one of us just has to mention matches for our eyes to twinkle.

I am still navigating my way through the contradictions. Societal restrictions continue to propagate. I still sometimes have to argue that “I am free”, although often it is my own self that needs reminding.

But the many images of Magda always stick in my mind; the scenes of Hawaa ‘ala al Tareeq concertinaed like the ever-dusty shuttered blinds in our Cairo home.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].