Running on empty: Oil-rich Libya hit by extreme fuel shortages

In Libya, a country where petrol was famously once cheaper than bottled water, a nearly two-month blockade of oil facilities by tribal leaders protesting the Tripoli government’s decision to deploy Syrian mercenaries has sent prices rocketing and boosted black market sales.

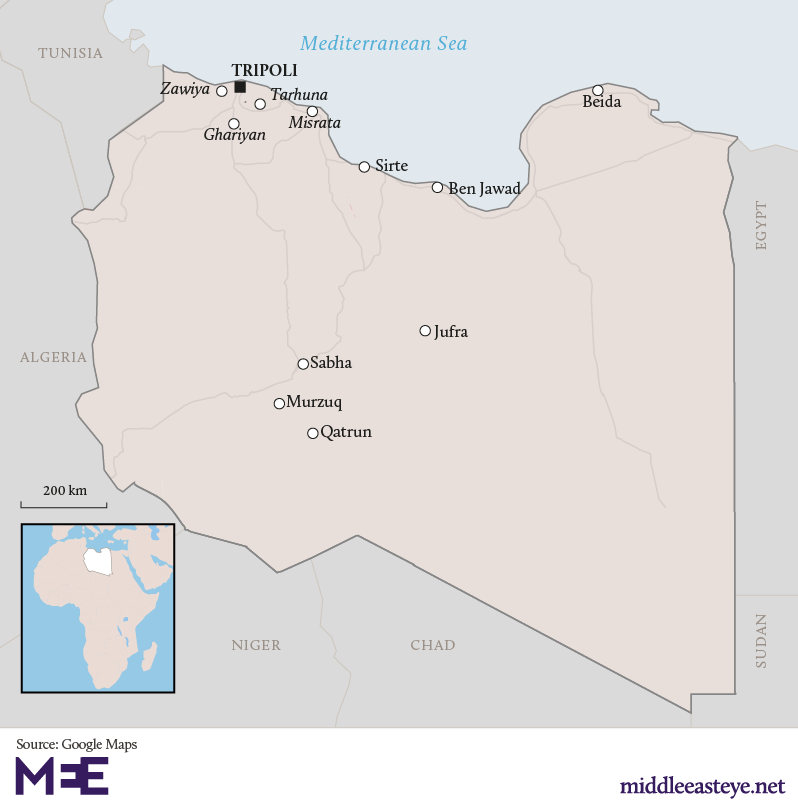

“Beyond the main coastal towns and cities, there’s literally no subsidised fuel for Libyan civilians now,” said Abdullah, 45, an engineer who lives near Sirte. “Most fuel, both in western and eastern Libya, is being sent to the frontlines.”

These are the crucial frontlines in the ongoing battle for Libya’s capital between forces loyal to the UN-installed, Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA) and a rival administration operating from the east of the country and led by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar.

“The situation is bad across the whole of Libya, but the very worst hit are the western and southern areas. Even before the blockade, there were shortages but now the situation is desperate,” Abdullah said.

Major price hikes

Libya’s heavily subsidised fuel should retail at 0.15 Libyan dinars ($0.11) per litre. This price is currently being maintained in eastern coastal cities and between Tripoli and Misrata, but most fuel stations beyond have hiked up prices.

Zawiya, western Libya’s only refinery and the country’s largest, stopped refining oil in early February when local crude supplies ran dry.

Libya’s refineries have never met local demand, but the country is now reliant on the imports that previously supplemented local deficit, both in the east and west.

Zawiya is selling imported fuel supplies at the hiked-up wholesale price of $0.58, according to local sources. This increase is, in turn, being passed on to the consumer.

With reduced funds for sufficient imports, Libya’s National Oil Corporation (NOC) is already warning of imminent countrywide petrol shortages.

'The further away you get from Zawiya, the more expensive fuel becomes'

- Abdullah, engineer in Sirte

“The further away you get from Zawiya, the more expensive fuel becomes,” Abdullah told MEE.

Having recently driven from Tripoli to Sirte via a lengthy diversion avoiding front lines and difficult checkpoints, he observed prices across a several-hundred kilometre stretch of the country.

“Gharyan is retailing at $0.90, Ashwayrif at $1.23, Sebha is around $1.42 and Jufra is now $1.43,” he said, referring to a string of Libyan towns.

“Official petrol stations have increased their prices a lot, although it’s not their fault because they’re buying it at five times the normal rate. But farmers have also started erecting illegal petrol stations - large tanks, sometimes underground, with a flow meter - and selling fuel illegally.”

These informal fuelling points were charging similar prices to official fuel stations, he added.

An Ashwayrif resident complained that, while the eastern government’s Libyan National Army (LNA) had its own military petrol station, nearby were makeshift fuelling points operated by farmers where petrol was being sold illegally at the price of $1.23. All this was being done under the noses of the military, who made no attempt to intervene.

“The [eastern government’s] interior ministry in Beida knows about these fake petrol stations but is not doing anything to stop it,” he said on condition of anonymity.

“It’s illegal - both the fuelling points and the price - but the LNA don’t seem to care as long as they still have their own station and fuel.”

Abdullah said GNA-affiliated forces were also turning a blind eye to such illegal fuelling points in areas under its control.

Running on empty

Libya’s eastern government is still maintaining the subsidised price of $0.11 in coastal towns technically as far as Sirte, but oil tankers have a long way to travel from the east to reach central Libya, and fuel stations keep running short.

“Tanker drivers are demanding exorbitant sums because of the 1,200km drive from the east, which they claim is difficult because of driving through the desert, and dangerous because they don’t know what might happen on the road,” said Mohammed, a shop assistant who lives between southern Tripoli and Tarhuna, and where petrol prices have doubled.

“We’re used to shortages because southern areas have long been neglected by Tripoli, and my family is OK because a relative works in a petrol station so, when fuel comes, we buy extra and store it in a shed at home,” he told MEE.

“But there have been no deliveries for a month, so we’re now using our stored fuel to get around.”

Mohammed said residents without such stockpiles had been braving a 550km round trip on a lengthy diversion avoiding current Tripoli frontlines to fill up in the capital, saying the distance meant most arrived home with just half a tank of petrol.

In Sirte, where there is currently no fuel available, either from garages or on the black market, residents are making a 300km round trip east to Ben Jawad to fill up their tanks, causing long queues at the town’s petrol stations.

“People are also filling up jerry cans or any bottles and jars with fuel, which they carry back in their cars, but this is very risky and there have been some accidents and you can see the burned-out cars by the side of the road,” said Abdullah.

Libya’s long-neglected south, ironically where much of the country’s rich hydrocarbon resources lie, remains the hardest hit.

“The whole of the south has serious fuel shortages,” said Ahmed, a resident in the southern Libyan town of Murzuq.

“When it’s available, fuel is $1.43 per litre and, in some places in the south, it has even reached $1.78. It’s a terribly difficult situation for us and we only expect it will become worse.”

Hassan, who lives in Libya’s southernmost town of Qatrun, where fuel is also currently retailing at $1.43 per litre, said: “Even though most of Libya’s oil comes from the south, it seems that we have no rights to Libya’s petrol. And there’s nothing we can do except wait until the governments in the east and west make an agreement.”

Worst blockade since 2011

Post-2011 Libya has been blighted by a series of oil facility blockades and reduced oil and gas pipeline flows to Tripoli by various players vying for influence, power and money.

But January’s closure of all pipelines carrying crude to Libya’s coastal oil export terminals from the south is the most comprehensive obstruction to date.

Although the blockade - a response to the GNA’s decision to deploy Syrian mercenaries into their forces via an agreement with Turkey - is widely viewed as being the work of Haftar, who heads the LNA, it is ostensibly being carried out by tribal leaders, who have gained dominance during eight years of neglect of Libya’s south by successive competing governments.

“The blockade is being done by tribal leaders, who are ordinary Libyans, as revenge for the GNA bringing terrorist Syrian fighters to Libya, as well as to try and stop Libya’s money being misused by Tripoli,” said a source with ties to several southern tribes.

“Of course Haftar is in the picture, but under the table, working with the tribal leaders. He has built good relationships with them, just as Gaddafi did, and it’s an effective approach in Libya.”

With Libya’s vast landmass lacking infrastructure and without any meaningful public transport, Libyans are heavily reliant on car travel, so the countrywide impact on civilians is profound.

But the ongoing blockade is also having a serious financial impact for a country almost completely dependent on oil revenues, and which is already suffering an economic downturn.

'It’s not like an engine you can just switch on and off'

- Muhannad, oil engineer

Since mid-January, production has plummeted from around 1.2 million barrels per day (bpd) to 95,837 bpd, understood to be mostly from the country’s two offshore facilities. This week, Libya’s NOC said that cumulative losses from the blockade were over $3.5bn.

Even when the blockade is eventually lifted, it will take up to a fortnight for crude to start flowing at previous rates, according to oil engineer Muhannad.

“The oil infrastructure will need maintenance before it can be restarted. It’s not like an engine you can just switch on and off. It’s a complicated process to restart a safe and steady oil flow,” he said.

“Pipelines are now sitting full of oil but they’re not designed to hold stagnant oil, which corrodes them. The maintenance and timeframe depends on the specifics of each plant. Some might be restarted in five days but others will need a minimum of two weeks.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].