Coronavirus and art: How Middle East artists have responded to lockdown

“Without great solitude, no serious work is possible.” These words - attributed to Pablo Picasso by a Spanish writer - appeared on the website of an Istanbul art gallery this month, one of dozens around the world forced to close its doors in recent weeks following government efforts to contain the Covid-19 pandemic.

The words might be of some comfort to artists in the coronavirus lockdown, working alone from homes or studios, with the art market facing the same financial crunch as almost every other industry. Smaller art galleries maybe better placed to exercise “social distancing” rules, but art sales traditionally follow the economy into a downturn.

Artists from around the world have found different responses to the pandemic, the global lockdown that has gone with it, and their own circumstances. Some choose to ignore or escape into their own worlds, some to engage.

One of the world’s most famous artists, the 82-year-old British artist David Hockney, released a group of iPad paintings from his home in France this month, including a picture of brightly blooming daffodils, titled “Do Remember They Can’t Cancel the Spring.” “I would suggest people could draw at this time,” he said from his house in Normandy, urging them to pick up a pencil, not a camera.

China’s Ai Weiwei - who once courted controversy with photographs of himself in the same pose as the body of a Syrian boy tragically washed up on a beach - has responded to Covid-19 in part with Instagram photos of his Facetime conversations with his mother.

Maysaloun Faraj, a London-based artist of Iraqi origin, has opted for something more old-fashioned. A Facebook group she started, Stayhome: Drawhome!, has gathered more than 300 members. Artists, amateur and professional, are invited to submit new works they have made of their own homes from the “inside looking in”.

Faraj first left Iraq in 1982, though she returned briefly before Operation Desert Storm in 1991. Though the current crisis pales in comparison to the experiences of her native country, the circumstances and imposed solitude have inspired memories of her days as an architecture student at Baghdad University in the 1970s.

Back then she practised her sketching skills by drawing traditional Baghdadi houses on the banks of the Tigris.

A painter, sculptor and ceramicist with work in major European and Middle Eastern collections, who has worked to promote Iraqi art on the global scene, Faraj's usual work is large scale geometric abstracts. Now she is finding “immense pleasure, peace and solace” - and producing charming work - through drawing every inch of her home from every vantage point possible.

“Despite the uncertainty and turmoil of today, there has been an abundance of solidarity, humanity, joy and beauty across the globe, and ‘earth’ is for the first time, in peace,” she told MEE.

“I feel more connected, not only with the present and what matters most, but also with the past, re-living treasured memories of what was once my home in that golden city at the heart of the cradle of civilisation.”

Among the artists in Faraj’s group - and also producing luminous works from the confines of her home - is Oroubah Dieb, a former art teacher from Damascus who now lives in Paris with her husband and fellow artist, Hammoud Chantout, and their daughter.

Under French lockdown laws they are allowed only one kilometre from their house. Dieb and her husband, who left Syria eight years ago, firstly for Beirut, studied art at university level in Damascus and ran a private art school there before the war, but no longer teach, depending on their savings and some exhibitions in the region.

“Sitting at home is an opportunity for meditation and some rest with the crowding of life here. But in Syria we have a lot of sorrows for nine years. Unfortunately, we have nothing new to us about the news of death, really,” she told MEE.

Responding to crisis

The war in Syria saw an early shift to artists creating digital work, including photography or video - easier and safer than painting in a studio, with art supplies not exactly a wartime priority.

The British Museum collected protest poster art from the early days of the war in Syria, and curators are watching for similar art to emerge from Yemen or Lebanon.

An exhibition of modern Middle East works on paper bought for the British Museum by a regional patrons committee, under the watchful eye of curator of Islamic and contemporary Middle East art, Venetia Porter, in an exhibition which was planned for later this year, includes maps by Iranian artist Nazgul Ansarina, responding to sanctions on Iran.

The works also include roses fashioned from newspaper accounts of political speeches by Tunisia’s Héla Ammar, and Iraq’s Hannaa Mallalah’s Street 1993, with her “ruins technique” using found and damaged fabrics or materials to reflect the destruction of war.

The British Museum's latest acquisitions in the group, mostly bought since 2009, are the striking black-and-white figures by Lebanon’s Paul Guiragossian, in La Misere Humain and La Mere Doloureuse, exploring Armenian suffering

Separately, in one notable 2014 installation, Homesick, the emigre Syrian artist Hrair Sarkissian took a different approach. He created a scale model of his family’s Damascus apartment, and filmed himself breaking it down with a sledgehammer - not something to be done during a lockdown.

Some Middle East artists have confronted the current global pandemic directly. Renowned artist Athar Jaber, born to Iraqi parents in Rome and now based in Antwerp, Belgium, carved ten face masks from marble, and put them up for sale, for €1,000 each. The project, which he has called A Mask for Life, is part of a Covid-19 fundraising initiative for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

“You can’t practise social distancing if you’re a refugee,” he says. “Around 70 million people are suffering displacement in crowded camps, awaiting in fear the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic.”

And Iranian artist Parviz Tanavoli, who has at times been the highest selling artist in the region at auction, has designed bronze and silver commemorative medals that will be sold at $600 and $1,500 to raise money for Iranian health workers.

‘Keeping On Keeping On’

But the majority of artists are simply finding ways to keep creating despite the restrictions.

Turkish fashion photographer Osman Özel created a photo and video chronicle of his time in a quarantine dormitory on the outskirts of Istanbul, housing more than 3,000 people, after he arrived in the city from Paris. His wife could visit to bring him daily necessities, but not see him.

“In my dorm room I am only allowed to open the window. I cannot go into the corridor or the garden. Without space, so much time becomes meaningless. I cannot sit still,” he wrote, in a journal for the Odunpazari Modern Museum, itself currently closed until at least early May.

One upside: he had been working on a prison documentary for several months, and “this might be the closest I’ve come to understanding what it is like to be in prison", he says. While he has chosen to talk to people less and less on his telephone, he kept taking photographs.

Several Turkish artists and collectives have worked to stage online exhibitions, performances, and “dialogues”. Online too, Turkish artists have set out to exchange and discuss bits of work in progress over 12 weeks.

Meanwhile, well-known Turkish artist Nancy Atakan, in a country heading for the highest rates of coronavirus infection in the region, has begun to research time systems of the past, “in particular the Ottoman concept of time because for me time no longer seems to exist the way it did a month ago.”

Aged over 65, she said, she has not left her home in four weeks.

“Artists in Turkey are definitely used to hardships, chaos, and uncertainty,” she told MEE, but added: “I don’t believe I have lived anything even close to this total shutdown in my entire life. There have been shortages, curfews and restrictions especially in the 1970s and 80s, but nothing like this.”

'Everybody is engaged in this issue but it’s time to feel, to take time, to analyse everything, to feel if there is another way of working'

- Massinissa Selmani, Algerian artist

In 2012, she noted, a Swiss curator, Susann Wintsch, spent several months in Turkey doing studio visits. She named the resulting exhibition, Keeping On Keeping On, marking the tenacity of Turkish artists. “To me, this title seems quite appropriate because we do seem to continue no matter what comes our way. Doubtlessly, we will also find a way to make artwork in the face of a more pronounced uncertain future.”

In the provincial French city of Tours, where leading Algerian artist Massinissa Selmani lives and works, to walk out, or drive to his studio, he has to carry a signed paper saying where he is going and why.

Each time he has to persuade puzzled policemen that he’s a working artist driving to his solo studio on the outskirts. “Every time you say you an artist they are a bit surprised. They don’t know what it is exactly, all the time I have to negotiate a little bit to say it’s my full job, all the time.”

Selmani’s drawings show people in strange, absurdist scenes, suggesting wry comments on social and political events. He would have been in Algeria now, visiting his elderly parents, who are scarcely going out.

In March he was due to show work in Drawing Now, the Paris art fair, now postponed. Instead, he is re-reading Algerian literature, to relax, and working on existing projects to keep “a normal rhythm”. “I never react immediately. ” he said.

The Palestinian artist Hazem Harb had just finished hanging his most recent solo show, Contemporary Heritage, at Tabari Artspace Gallery in Dubai, the culmination of six months' work, when lockdown took hold. "As a Palestinian I’m used to cultivating creativity in restrictive circumstances," he said. Rather than lamenting the loss he got to work preparing a virtual tour.

Now busy drawing and researching in his Dubai studio, Harb is a rising star whose nostalgic reflections on Palestinian life have been shown worldwide.

“The tensions and shifts in social circumstances will invariably impact art as they do everything else from politics to economics, but this doesn’t have to be direct or obvious," he says, recalling another quotation from Picasso, art's great modern master and creator of Guernica. “I didn’t paint the war,” the painter said, as Europe began to emerge from the violence of the Second World War. “But there’s no doubt the war was in my pictures.”

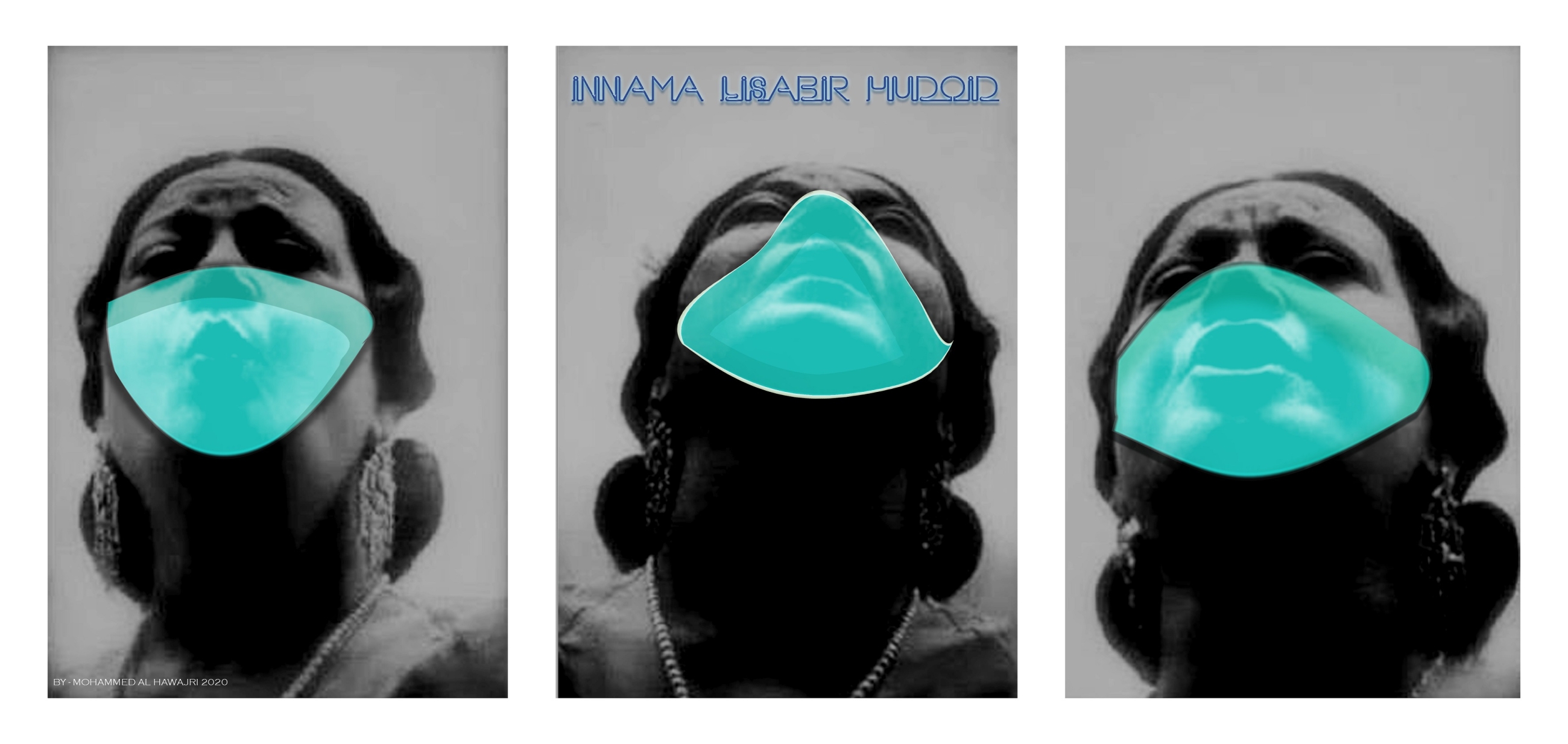

And in the Gaza Strip, where streets emptied after the Palestinian Ministry of Health announced the first two cases of coronavirus on 22 March, the Palestinian artist Mohammed Al Hawajri at first stuck to writing down ideas for life after the immediate crisis - saying he could not do artwork that expressed the epidemic “because the tragedy is greater than the idea of artwork”.

Then Hawajri, whose practise ranges from sardonic “red carpet” installations in the setting of Gaza, to powerful portraiture, opted to produce images inspired by the Arab singer and cultural icon Umm Kulthum... donning a mask.

Now he spends his time gardening on the roof of his home. Artists will have plenty of material to work on after the virus, he says - like the phenomenon of men, rather than women, doing household tasks, from cooking and cleaning and kneading dough.

He speaks of a “state of fear” among the two million people living in the over-crowded enclave, but praised the “patio initiatives” of musicians and singers who play tunes from their porches.

“I always say that I am the most fortunate person to be an artist,” he told MEE. “I live my life inside my studio from which I escape from wars and sieges. I always draw my own world and express my concerns and concerns around me with the simplest tools that reach the world."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].