REVEALED: How a British-backed media operation tried to turn Alawites against Assad

A web-based protest movement that claimed to be a grassroots campaign by members of Syria’s Alawite community was actually created on behalf of the British government, official documents seen by Middle East Eye have shown.

The campaign known as Sarkha – or “The Cry” – purportedly began in 2014 in the coastal city of Tartus as a response to the high level of casualties among Alawite men serving in the Syrian government’s armed forces.

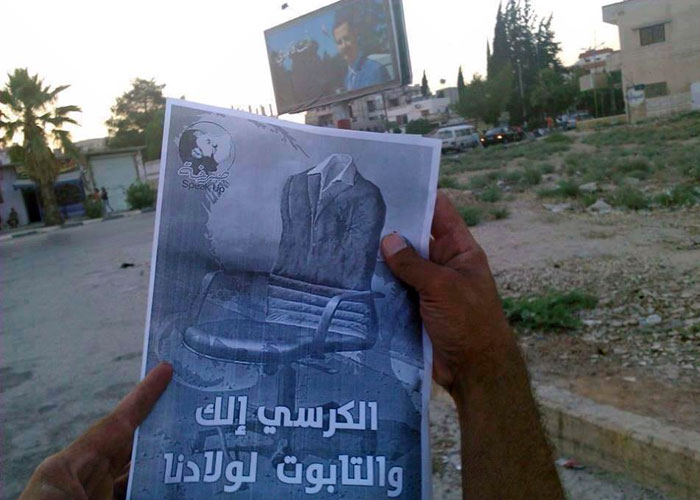

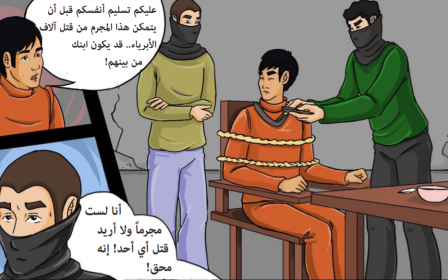

There was a Sarkha Facebook page, Sarkha leaflets, online reports of Sarkha posters being plastered on the town’s walls and short videos posted on social media showing young men spraying the campaign’s slogans on walls.

Before long, there were reports online that the campaign had spread to the city of Latakia and the island of Arwad, as well as other coastal areas that are home to the Alawite sect from which Syrian President Bashar al-Assad hails.

In a short period of time, the campaign was drawing support in most parts of the country, with its main Facebook page receiving around 100,000 likes before evolving into a website.

Made in New Jersey

However, the documents seen by MEE show that Sarkha was in fact devised by an American company, Pechter Polls of Princeton, New Jersey, working under contract to the British government.

Initially, the contract was managed by a unit at the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MoD) called Military Strategic Effects.

Responsibility for its management was then transferred to a British government fund called the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), which aims to tackle conflicts that threaten UK interests.

The UK government’s hand remained hidden as media outlets across the Middle East reported on Sarkha, describing it as having been “launched by civil society activists” who were concerned by high casualty rates among Alawites serving in the government’s armed forces.

The campaign highlighted those deaths and injuries, and also said that a high number of young Alawite men were deserting from the army, while others were detained in government prisons.

Its underlying message was that members of Syria’s Alawite communities needed to denounce sectarianism, connect with Sunni Muslims and other ethnic and religious communities in the country, and accept that Bashar al-Assad, while a fellow Alawite, was also a tyrant.

Sarkha was later rebranded as a campaign called Same Pain. An examination of the Same Pain Facebook account shows that it was launched as Sarkha on 15 July 2014, became Speak Up seven days later and was changed to Same Pain on 25 October 2017.

'No impact or presence'

One activist who was involved in the campaign said: “There is a financier who pays you and plans to end the sectarian problems in your country and raise the voice of the oppressed, and this is not bad. I am confident of my work and the message I did, whatever the source of the funding.”

However, he added: “I do not think we were completely successful. When the campaign ended, the contact person for Alawites left for Europe.”

REVEALED: The UK's covert propaganda campaign in Syria

+ Show - HideIn February, a Middle East Eye investigation revealed details of a British government propaganda campaign in Syria which sought to promote the UK's strategic interests through support for the “moderate armed opposition”.

MEE is now publishing details of an internal assessment revealing concerns and divisions within government about the effectiveness and appropriateness of that campaign. It reveals the work was being conducted despite concerns that it was illegal. Many risking their lives as citizen journalists and activists on the ground were not aware of London's involvement.

Some Syrian activists involved in British-backed projects have defended the work, saying they were dependent on western support for funding. Some complain that western countries should have done more to support the opposition and that support for their work dried up as the war tilted in Damascus's favour. Others say the work may have been counterproductive.

Some journalists working for Syrian state-controlled media in the coastal cities of Tartus and Latakia were shocked to learn how the campaign was devised and funded, with one describing it as “suspicious and not real”.

Both journalists working in government-controlled areas and opposition Alawite activists questioned whether the campaign had gained any traction.

“This campaign had no actual impact or presence,” said a journalist in Tartus.

An Alawite dissident originally from the coastal town of Jableh said that Syria was in “desperate need of campaigns to end sectarian loyalties”, but said of Sarkha: “I have never heard of it.”

He also questioned the effectiveness of online campaigns intended to stir up opposition sentiment in government-controlled areas.

“In general, the use of non-neutral phrases by any page results in people being afraid to interact with them for fear of security issues,” the dissident said.

“There are many who agree with the campaign, but who cannot express their opinion or even sympathise with it.”

The documents show that Sarkha was one of five main propaganda programmes that the UK was operating in Syria at this time.

They were all described within British government circles as “strategic communications” initiatives, rather than propaganda programmes; Sarkha is shown to have been known to British strategic communications officials by the term “AWBP” - the Alawite web-based platform.

Earlier this year MEE disclosed that as part of these propaganda programmes, the British government covertly established a network of citizen journalists across Syria during the early years of the country’s civil war in an attempt to shape perceptions of the conflict.

Frequently, the individuals who were recruited were unaware that they were being directed from London. A number were killed during the conflict.

Initial blueprints for at least three of the five programmes were drawn up by an anthropologist working in counter-terrorism for the British foreign office in London.

'Sectarian spillover'

An assessment of the effectiveness of the five main programmes that was conducted on behalf of the CSSF in July 2016 describes Sarkha’s aim as being to “create a safe, secure, social media platform for the Alawite people to discuss and exchange idea about their needs, lives and future roles in a post-revolutionary Syria”.

Its budget from the CSSF during that financial year was £600,000 ($746,000), the documents show.

The review noted that “the inevitable sectarian spillover of the civil war” was a “political minefield”, but concluded that Pechter Polls had successfully navigated this by “holding the regime rather than its co-religionists responsible” for the many dilemmas and tragedies of the conflict.

Its authors added: “As tensions revolve primarily around pro- or anti-regime affiliations, rather than location, host/guest status, or some other dichotomy, Pechter Polls’ content and outreach activities attempt to mitigate this tension by emphasising commonalities and narrowing the circle of blame to the regime’s inner core.”

Unlike the British government’s other propaganda initiatives, which often relied upon Syrians inside the country for delivery, Sarkha appears to have been largely operated from Pechter’s offices in Princeton and was considered to pose little risk to those involved, the CSSF review said.

The review was scathing about the UK’s propaganda initiatives as a whole, however, concluding that they were incoherent, poorly planned and cost lives.

The review also concluded that the propaganda programmes posed a “major risk” of contravening UK law.

The documents seen by MEE do not shed any further light on this perceived risk.

However, the UK’s Terrorism Act 2000 defines “terrorism” as the use or threat of any action that involves serious violence, risk to health, or damage to property, if that action is intended to influence any government, anywhere in the world.

Pechter Polls has worked in the Middle East for some years, conducting telephone opinion polls. It carried out a number of these in Egypt during the 2011 revolution.

MEE has repeatedly asked the company for comment but has not received any response.

The UK's foreign office declined to comment and did not respond to a series of questions about its propaganda operations in Syria, including questions about the risk that they may have contravened British law.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].