Is the collapse of the Gulf Cooperation Council's rentier state imminent?

Dania Thafer| Saudi Arabia is addicted to the rentier model until the oil runs out

The social contract of Saudi Arabia and other Arab Gulf states is a deep-rooted systemic structure that is linked to the institutional design of the economy, society and political environment.

State-conferred financial benefits to Saudi nationals fluctuate depending on circumstances and they have yet to cross the threshold that would redefine the fundamentals of state-society relations.

The question that still lingers is not if intrinsic aspects of the rentier social contract will change, but rather when?

The cyclical nature of the oil industry is one of boom and bust and so consequently prices will likely rebound in the long term. Likewise, the social contract is not a switch that is turned on or off; elements of it fluctuate akin to the oil market during economic growth and decline.

In 2015, during the last economic downturn, Saudi Arabia put into effect austerity measures, which included a cut in subsidies that resulted in higher utility costs for Saudi nationals. Shortly thereafter, in 2016, certain allowances, bonuses and financial benefits for civil servants and military personnel were cancelled and suspended.

Yet, in 2017, these allowances were reinstated, coinciding with the change in succession as Mohammed bin Salman was appointed as the crown prince. Then in 2018, Saudi Arabia increased salary allowances to lessen the strain of the initial introduction of the 5 percent VAT tax and removal of subsidies.

Now once again there is a rescinding of those same 2018 allowances coupled with the tripling of VAT to 15 percent, bringing the tax rate closer to the global average.

Arguments that the VAT rise will affect the material legitimacy of the Saudi monarchy through the notion of "no taxation without representation" are half-sighted. Studies have shown that Gulf citizens are more open to VAT than other fiscal measures.

It is important to be vigilant that VAT is an indirect consumption tax that is levied on select goods and services during the supply chain process until the point of sale. Saudi Arabia has been deliberate in making sure not to impose direct taxes on its citizens, although there was a short-lived instance in 1950 in which it instituted personal income taxes and other taxes.

Based on past trends, the Saudi government has seized the opportunity of economic downturns to implement long-overdue reforms, such as levying VAT and subsidy reforms. However, these are carefully selected measures that still allow for the preservation of the core tenets of the social contract.

Social benefits such as allowances, which reward citizens for their political acquiescence during booms and then readjust them during busts, will likely remain a cyclical tool of the Saudi rentier state. We will likely continue to witness the Saudi state shift the majority of the burden of the current economic downturn onto expatriate workers rather than nationals.

The kingdom's social contract is slowly evolving, but the fundamental rentier state-society dynamics remain the same. As Saudi Arabia continues to be addicted to the rentier model, the underlying aspects of the social contract will likely remain intact until the oil runs out and/or becomes obsolete.

The end of the oil era has yet to be realised, even during the current catastrophic Covid-19 crisis. The question that lingers is not if intrinsic aspects of the rentier social contract will change, but rather when?

Bill Law| Saudi and UAE have a vested interest in keeping the rentier model intact

The rentier state model has proven itself resilient over several decades so I do not think that it is the beginning of the end. But this is not to say that changes to the model are not underway.

The introduction of VAT, in place in several Gulf states since the beginning of 2018, and the austerity measures forced on those states by, among other things, the current crash in oil prices, will make a difference as to how their subjects view the social contract.

The wealth and how it is distributed remains firmly in the hands of the ruling families. They have shown no inclination whatsoever to give that up

The key issue though is that they are subjects, not citizens, and thus subjected to the whims and vagaries, the numerous economic reform plans, all from the top down, that have come and gone as the price of oil falls then rises.

The most recent and the most sweeping is Mohammed Bin Salman’s Vision 2030. Like so many other plans before it, it will never reach its lofty and over-optimistic targets.

But there has been a huge shift in Saudi Arabia. However, it has to do with social attitudes such as the bringing together of men and women in work and other public environments, the opening of movie theatres, the importation of popular western musicians and sports stars.

But the wealth and how it is distributed remains firmly in the hands of the ruling families. They have shown no inclination whatsoever to give that up. MBS treats the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) as his own bank to do with as he likes and no one is prepared to challenge him, even when the decisions he makes, such as giving Masayoshi Son’s Vision Fund $45bn from the PIF in 45 minutes, are palpably reckless.

It may be that when peak oil hits, that is the point at which global demand for oil falls permanently, the rentier model will be at risk. There are disagreements about when that will happen. Some experts suggest 2030, other say a decade later, some even say it is happening now.

I expect the most realistic date is 2030 which should give MBS the time he needs to wean the kingdom off oil dependency. Other states such as the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait are further down the road. Qatar is fortunate in that it has an abundance of natural gas and the infrastructure to liquify and export it to global markets.

Bahrain and Oman are the most vulnerable economies and it is in those two states that the social contract is most at risk. But I expect that the wealthier states will continue their financial support to keep those rulers afloat. They have a vested interest in ensuring the rentier model remains largely intact.

Rachel Ziemba| Weaker finances may increase the influence of China in the region

The rentier state seems to be part way through death by 1,000 cuts rather than an aggressive shift to a new social contract stemming from new mutual obligations of taxation and representation.

The crisis has stepped up prior efforts to increase spending efficiency, cut subsidies and moderately reduce reliance on oil and gas revenues - but ultimately the revenue concentration and size of the public wage bill will limit the degree of change.

The biggest challenge remains in Saudi Arabia, where austerity will disproportionately impact middle-class Saudi nationals

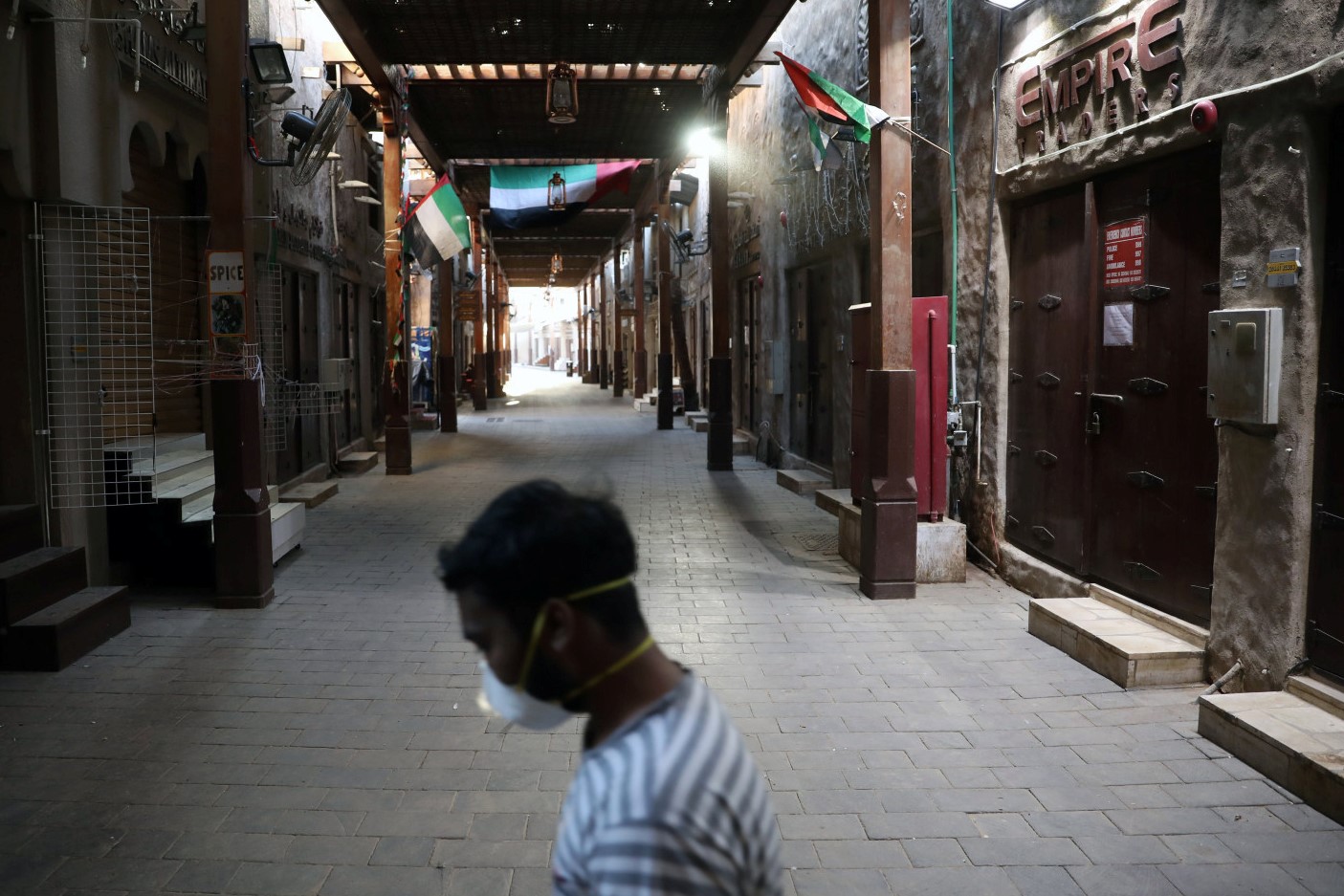

The rentier state has been under pressure for some years, especially since 2015, but the combined Covid-19 health, economic, financing and energy crises prompt some very difficult decisions. Overall the social contract of public-sector wage increases, transfers to the population and development of local service sectors is increasingly unsustainable - but the shift will be slow.

Despite the increased challenge, the government of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states remain unwilling to move away from the patronage system and the large public wage bill. If anything, the challenges to tourism and mega projects and need for competition will actually increase the importance of the government in driving the broader economy as the private sector faces greater financial and demand pressure.

The reduction in allowances in Saudi Arabia coupled with an increase in VAT will raise the cost to households while delays in major projects will likely exacerbate the hit to non-oil growth.

The crises will put additional political pressure on nationalising the workforce and increase the cost of hiring expats, leading to more competition within the GCC (on relative tax and regulatory environment) and make GCC governments more picky about where they invest their funds in the Middle East and Africa region.

Sovereign funds, including development funds like Mubadala, Mumtalakat and Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund and Kuwait’s fund for future generations will face additional pressure to invest at home, taking on more development projects, while more broad investment funds will continue to receive less capital.

Oman and Bahrain remain much less able to maintain their spending plans, but debt restructuring and regional support rather than austerity are the more likely outcomes as they try to make it through 2020-21 debt repayments.

UAE and Qatar will experience more extensive flight of higher-paid expats, which will hit local consumption and tourism, and trigger some coordination and consolidation. The biggest challenge remains in Saudi Arabia, where the composition of austerity will disproportionately impact middle-class Saudi nationals, who face additional costs and challenges entering the workforce.

At the same time, with less foreign study, there is an increased risk that countries of the Gulf will turn inward and increase local competition. Weaker finances will put more pressure on the foreign policy choices of Oman and may well increase the influence of China in the region.

China so far remains reluctant to commit to spending more in the region and providing fiscal and credit lifelines.

Andreas Krieg| MBS' hardest test: Offering more bread than circus to Saudi youth

The fallout of the global Covid-19 depression paired with a historic contraction of the oil market has thrown the Saudi rentier state into severe crisis. The old slogan of no representation without taxation no longer holds as the kingdom is bracing for an unprecedented economic and financial crisis that does not allow the Saudi welfare state - that for years has been in decline - to provide public welfare inclusively at a level that citizens have become used to.

The question is whether MBS can draft a new social contract that is inclusive in providing public goods to all Saudis beyond the shrinking group of confidants surrounding the future king

While the public has been prepared by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman since 2017 that Saudis will have to tighten their belts and contribute more to the public good, the announced rise in taxation and benefit cuts last month comes at a time when the Saudi Public Investment Fund continues to engage in high-profile investments overseas with dubious returns.

Anti-corruption measures taken over the past few years, although they could have been steps in the right direction, have often been political moves that target those outside MBS’s patrimonial networks. Many privileges of the royal family remain as MBS cannot afford to risk undermining a fragile balance in an Al Saud-dominated kingdom that often still looks like an extensive family business.

It is therefore questionable as to what extent investments made overseas actually come to the benefit of average Saudis and much-needed private-sector infrastructure in the country.

The great test for MBS will be whether he can win over the youth, not just by lifting societal restrictions and offering mass entertainment, but by offering more bread than circus, getting the youth employed outside a contracting public sector or a hydrocarbon sector in crisis.

The confidence in the Saudi crown prince will take a hit if authoritarian measures introduced by the state come amid an increase in the burden borne by the average citizen whose say in the running of the country and the spending of its taxes is not widened.

The gradual collapse of the Saudi rentier state, as across the Gulf, is only a matter of time, which might become reality in the kingdom earlier than elsewhere. The question is then whether MBS can draft a new social contract that is inclusive in providing public goods to all Saudis and access to policymaking beyond the shrinking group of confidants surrounding the future king.

David Wearing| Mohammed bin Salman's Vision 2030 is dead

In 1994, during another period of low oil prices and fiscal tightening in Saudi Arabia, the Guardian reported that "it is virtually impossible to talk to an educated Saudi - in or outside the government - who does not believe that [the British and the Americans] are bent on … milk[ing the kingdom] for weapons sales".

One interviewee from Saudi officialdom described the Atlantic powers as "blackmailers", another as "bloodsuckers".

The challenge for the House of Saud has always been to satisfy two constituencies: its subjects and its foreign protectors

The challenge for the House of Saud has always been to satisfy two constituencies: its subjects and its foreign protectors.

Deployment of petrodollar wealth has served it well in both cases, but the latest in a long line of misjudgments by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman - launching an oil price war at the start of a global collapse in demand - has choked off the national income and brought the regime to a point of reckoning. The economic future for fossil fuels was looking less and less promising even before the onset of Covid-19. If oil prices never fully recover, then real pressure will quickly start to build.

Saudi subjects may reflect that the government which has just trebled VAT and removed allowances for public-sector workers is the same government that spent £15bn on arms from BAE Systems alone over the past five years.

They may ask why the national sovereign wealth fund has spent $7.7bn this year buying up stock in blue chip US and European companies, during a supposed period of national austerity, especially when three of those firms - BP, Shell and Total - are oil majors, and the kingdom’s entire predicament is the result of its decades-long failure to diversify from oil.

Likewise, the western powers, upon whom the Saudi royals have always depended for their security, may wonder how much longer such spending sprees can last, given the emerging economic realities.

If oil loses its strategic value as the lifeblood of the world economy, and if petrodollar wealth is no longer available to help finance Anglo-American current account deficits and bankroll their military industries, then what remaining value will those powers perceive in what has become a deeply embarrassing alliance with an increasingly dysfunctional Riyadh?

The revival of Barack Obama’s attempts to more carefully balance the West’s relations with Saudi Arabia and Iran will likely follow the demise of the Trump administration.

The wisdom of Vision 2030 as a regime survival strategy was never entirely compelling. In an age of austerity, that supposed "vision" now lies dead in the water. The next chapter will be fascinating.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].