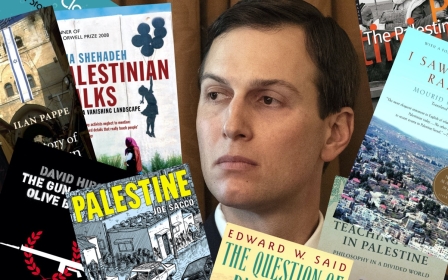

Palestinian writing: Maps redrawn, futures reimagined

Maps can be repositories of cultural memory, a way of situating ourselves in time and space, and guides to a possible future. But they can also be used to exclude, and to rewrite history to erase shared memory.

It is this idea of re-mapping that the people behind literature and history project PalREAD are seeking to address. The project launched in 2018, the brainchild of scholar Refqa Abu-Remaileh. The project, she says, “seeks to re-trace and re-gather the scattered fragments of the story of Palestinian literature”.

Previous PalREAD events have been held at the Free University of Berlin, including a 2019 Mapathon, where system design engineer Majd al-Shihabi taught participants to extract data from Palestine’s Mandate-era maps.

A January 2020 talk followed migratory journeys from the Ottoman Empire to South America. The latter featured Mexico-based Palestinian literary translator Shadi Rohana and world-renowned Palestinian-Chilean novelist Lina Meruane. An event in February linked Palestinian literature with North and Latin American indigenous stories.

Over the next month, a new series of globally accessible readings and lectures titled Re-locating the Map, hosted by series organiser Ruth Abou Rached and featuring four prominent writers and scholars of Palestinian literature, is being launched. Set to unfold across four live online events, it marks a chance for a wider public to engage with the project.

These new talks also trace migrations within Palestine and beyond.

“Many debates about Palestinian creative expression seem to seek to 'map' where it 'is', should or could be,” says Ruth Abou Rached. These talks aim to “encourage participants to consider where and how many Palestinians are 'mapped' in particular ways.”

The PalREAD project was inspired by a number of digital initiatives of the last several years, making Palestinian stories more widely available. Among them are the Palestinian Revolution project; Past Disquiet; Palestinian Journeys; the Khazaaen project; and the Palestinian Museum’s growing digital archive.

All of June and July’s Relocating the Map events will be open to the public. Abu-Remaileh says she hopes that anyone interested in Palestinian and diasporic stories will come hear these four speakers, who promise to chart Palestinian stories across space and time, through the past, present and future.

Ghayath Almadhoun

All Roads Lead to Berlin is the first in the series on 16 June by Palestinian-Syrian poet and filmmaker Ghayath Almadhoun, who is currently in Berlin with an artist-in-residence programme. The first point on the poet’s personal map was in the Yarmouk refugee camp, where he was born to a Palestinian father and a Syrian mother in 1979.

Almadhoun published his first poetry collection aged 25. Two years later, in Damascus, he co-founded the Bayt al-Qasid (House of Poetry) with Lukman Derky. But his time there was short-lived; Almadhoun was not yet 30 when he left Syria and sought political asylum in Sweden.

“In 2008, I was invited to read my poetry in Stockholm, and I sought asylum,” he told LyrikLine in 2015. “Why? Look what is happening in Syria and you will know what kind of dictatorships I fled from.”

His poetry, as Abou Rached says, marries a depth of vision to ironic wit. Many of his prose poems explore how landscapes can be erased and rebuilt. In his long poem Schizophrenia, translated by Catherine Cobham, Almadhoun writes about Ypres, a city in Belgium that “was wiped off the map in the First World War just as the Palestinian people were wiped from school textbooks and the records of history”.

In the prose poem, Almadhoun’s narrator declares himself a “Palestinian-Syrian-Swedish refugee, wearing Levi’s jeans invented by a Jewish immigrant from Germany in San Francisco,” and he goes on to map himself, Palestine, and Ypres:

…one hundred years after its destruction or one hundred years after its reconstruction, in the city of Ypres where you can put your hand on history stretched out before you like a corpse, touch the wound and find out that it’s still hot like a woman’s nipple melting between your lips, I walk, the Palestinian refugee who up till a short time ago was omitted from all books, news, academic research and official enquiries, for, as we all know, Palestine is a land without a people.

Almadhoun’s most recent collection of poems, Adrenalin, examines the erasure of places, but also the ways in which they are rebuilt.

In a reconstructed city like Berlin lies a secret that everyone knows, which is that the...

No, I will not repeat what is known, but I will tell you something you don’t know: the problem with war is not those who die, but those who remain alive after the war.

Almadhoun will give a reading of his work, following by a Q&A.

Bashir Abu-Manneh

The second talk, An X Over Your Apartment, on 23 June is by scholar Bashir Abu-Manneh and promises to map the recent past. Abu-Manneh is interested in how Palestinian writers have grappled with tracing Israel’s “war on terror,” launched in 2000.

Abu-Manneh, author of The Palestinian Novel: From 1948 to the Present, said his talk will ask: “What does it mean for an occupying power to launch wars against those it occupies in the context of the Oslo peace process?”

Palestine has seen several wars in the two decades since the 2000 Camp David Summit and, “for this talk in particular, I'm interested in the wars launched by Israel after 2000 in occupied Palestine: West Bank 2002, Gaza 2008-9, 2012, and 2014. And in the Great March of Return protests of 2018-19.

This literature includes, Abu-Manneh said, Najwan Darwish’s collection of poems, Nothing More to Lose, translated to English by Kareem James Abu-Zaid, and Atef Abu Saif’s The Drone Eats with Me: A Gaza Diary.

Najwan Darwish is very good at mapping “suffering's glow,” Abu-Manneh said, while Abu Saif gives us a picture of “the non-logic of war, how a war on civilians is impossible to predict as everyone is a potential target and nowhere is safe.”

In The Drone Eats with Me, written in the summer of 2014, Abu Saif, who is now the PA's culture minister, brilliantly lays out what it feels like to be a target:

My point is: when you listen to the radio, you get the feeling everything is slowly collapsing around you. Each time you hear of a loss of life somewhere else in the Strip, your mind calculates the distance between there and here; you picture a map of the Strip with the latest target and the next one – you. The numbers of the dead, the screams of the injured, the cries of their families; these all make up the sound track to this map, which has an X over your apartment.

Lindsey Moore

The next talk, Drones and Clones, on 30 June will map the future, as Lindsey Moore, a lecturer at Lancaster University in the UK, explores how speculative fiction can re-envision Palestine. Dystopia - or an inverted utopia - is a common construct in Anglo-European science fiction.

But in Palestinian literature, Moore said, dystopia is different: "In Thomas More’s paradigmatic text of 1516, Utopia is artificially isolated from neighbours that it forcefully subdues and disenfranchises. Sound familiar? Palestinian writers evoke dischronotopia: multiple, hierarchised time-space configurations in one tiny geographical place.

"You can’t go to the West Bank - if you’re privileged enough to get in - and miss the managed discrepancy: there’s a refugee camp on one side of the road and an Israeli settlement on the other; the skyscrapers of Tel Aviv are visible from the hills of the West Bank."

In Moore's conception of a dischronotopia, there are many microclimate dystopias, and characters cannot see each other across time and space.

This is true of Palestinian science fiction stories such as Majd Kayyal’s N, translated to English by Thoraya El Rayyes, where some Palestinians live in a parallel universe. It’s even more true in Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance, available in translation by Sinan Antoon. In Azem’s book, Palestinians simply disappear, and Israelis cannot see them anywhere.

Moore said that she is examining how science fiction, in novels and stories such as these, can change how we look at space-time configurations.

Nemat Khaled

The final talk, Mapping Women’s Stories, in the series, on 7 July, will be with Syrian-Palestinian author Nemat Khaled.

Khaled also lived in the Yarmouk Camp, after her family had to flee the Golan Heights in 1967, when Syria lost the region to Israel. She was forced to leave Syria in 2015. Her home, which once had 15,000 or 16,000 books, has been destroyed.

"I saw a video of my house," she said, in an interview with L’art de Sobrevivre. “It is destroyed: there are no walls, no library.”

'All my memories are in Yarmouk: my family, my friends, the people I love… I know all the streets'

- Nemat Khaled, author

Khaled grew up among her parents’ and grandparents’ stories about Palestine, but she also put down roots in Yarmouk. Khaled told L’art de Sobrevivre: “All my memories are in Yarmouk: my family, my friends, the people I love… I know all the streets [of her Golan home].”

Or at least she knew them. Now that Syria is immersed in war, she is no longer so convinced: "Now I would be lost if I went back because it is completely destroyed."

One of Khaled’s best-known novels, Laylat al-Henna (Henna Night), maps the lives of women in this disappeared Yarmouk. The novel opens with Nadia in despair at the betrayal of her cousin, Djalal, who she thought she would marry.

As German writer and reviewer Volker Kaminski writes of the novel: "Instead of being able to celebrate the ubiquitous henna night, which traditionally takes place before a wedding, Nadia sinks into a desolate 'henna night of desperation' from which she is no longer able to find a way out."

Organiser Ruth Abou Rached said that even though she is a recent arrival, Khaled is among the most active Arab literary figures in Berlin, both as writer and a literary critic.

“Nemat's stories,” she said, “re-create and pay tribute to vital, lived Palestinian traditions and memories whose locations and experiences may be forgotten.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].