Why I'm no longer talking to white people about Palestine

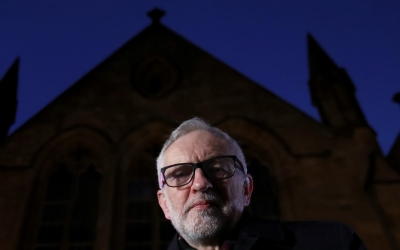

Last December, in a pub, fired up after an election night TV leaders' debate, I ended up in an argument about why former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn should not have been trapped into refusing to apologise over antisemitism by BBC presenter Andrew Neil.

I raised the argument that there is an Israeli influence working strongly within our democracy. I was asked to stop talking immediately by a white British man whose wife is Israeli. I informed the group that my cousins had experienced torture in Israel so this is not just theory to me, and it was also directly affecting the election in the UK.

I was asked again to be silent. I looked at their calm faces and felt like an hysterical Arab woman.

Uprooting Palestinians

In the early 1990s, pre-cheap flights and in search of adventure, many of my fellow Nirvana-listening, festival-going, vegetarian friends spent part of their gap year in Israel working on a kibbutz. Blue air mail letters arrived, telling me excitedly about the community spirit, sunshine and joy of hard work. This sat uneasily with me, but I didn’t know why.

I knew the suffering of 1948, the uprooting of Palestinians, the inequality between Israelis and Arabs, and the world turning its back on the Palestinian cause

My parents, from Palestine and Jordan, had protected me from the subject of Middle East politics, but I’d overheard too many discussions over arak and the crack of salted pumpkin seeds. I asked my father many questions, from “Why was Richard the Lionheart, who butchered many an Arab, a hero of British history?” to “Why are my friends going to build in Israel?" He replied with a stoic shrug: "They are misled."

There was still something missing: it baffled me that my liberal-minded friends were there. I didn’t understand the dream to build a utopian state, with male and female equality - pioneers and idealists, with khaki sleeves rolled up, mucking into the new land.

I knew the suffering of 1948, the uprooting of Palestinians, the inequality between Israelis and Arabs, and the world turning its back on the Palestinian cause. I remember the moment I first saw a world map where Palestine was not named.

Positive discrimination

In the years after 9/11, people became dimly aware that Arabs were not the same as Pakistanis or Indians. It was a faltering start to coming to terms with the existence of Palestinians.

Then came the solidarity: white people wearing keffiyehs, the Free Palestine badges, lovely posh ladies petitioning outside HSBC over the bank’s investment in illegal West Bank settlements.

Gradually, the food and culture of the Middle East seeped into British life, via Waitrose and food writer Yotam Ottolenghi. After falafel, people started using zaatar and sumac. "Is that Ottolenghi?" people would ask about my cooking. "No, it is a classic Palestinian dish! Yes, my family were Christian; Bethlehem is in Palestine.”

Within the arts, I enjoyed my first taste of positive discrimination through organisations such as the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC). It was only then that I realised the structural racism that I took for granted, never expecting to work in such a hallowed British institution. I remember the wide-eyed surprise on day one at the RSC, working on the play A Museum in Baghdad with an almost entirely Arab cast. “They’ve let the Arabs in!” one actor whispered with a giggle.

Dangerous extremes

Some years ago, I was on a merry night out in Liverpool with a Jewish actor, having performed a play about occupation, when some lads asked me where I was from. They didn’t ask my friend, despite his strong Pittsburgh accent.

As with all discussions of race and power, language must be analysed forensically and used sensitively

When I replied, one of them roared: "Free Palestine," before making derogatory remarks about Jews, adding "bring back Hitler". I looked at my friend aghast; he returned a secret smirk of "I told you so". Perhaps this lad was a random drunk, but it was the first time I’d heard such a dangerous extreme of ignorance and hate speech, with which I was expected to collude.

It’s not “the Jews”. It’s not all Israelis. I have seen British people picking up the Palestinian flag and running with it, sometimes clumsily, down the wrong road. This has caused damage to the Palestinian voice in British debate.

As with all discussions of race and power, language must be analysed forensically and used sensitively. Are we talking Israelis and Palestinians, or Jews and Palestinians; Israelis and Arabs, or Jews and Arabs? I stand by Why I'm No Longer Speaking to White People About Race author Reni Eddo-Lodge’s words on racism: “There is an unattributed definition of racism that defines it as prejudice plus power.”

I have seen British people picking up the Palestinian flag and running with it, sometimes clumsily, down the wrong road

By this definition, Palestinians cannot be racist towards Israelis, as they are not the ones in power. Yet, if I was to say that Jews are more powerful than Palestinians, this would be racist and buying into “Jewish conspiracy theories” - which Labour leader Keir Starmer recently used as a reason to sack Rebecca Long-Bailey.

Conflating ethnicity with nationality silences the Palestinian voice in the fight against racism. Worse still, by describing it as antisemitic, it implicates all Jews in the racist policies of Israel.

Bringing down Corbyn

Who is deciding upon the language we use - Palestinians or Israelis? It seems we are spending a lot of time discussing semantics on the eve of Israel's latest annexation.

We have a prime minister who has referred to Black Africans as“picanninnies” and Muslim women as “looking like letterboxes” - with the feeble excuse of standing up for women’s freedoms. But we are silenced from discussing the policies of one of the most militarised countries in the world.

We now know of the perfectly timed complaints, engineered and orchestrated from within the Labour Party, designed to bring down Jeremy Corbyn, the only one brave and mad enough to stand up for Palestinians. He was decimated by slurs of antisemitism. Meanwhile, so little has been exposed of the racism within the party directed towards Black MPs, such as Diane Abbott and others. Sadly, there is a hierarchy at play, and Palestinians are very near the bottom.

It has taken the Black movement hundreds of years to become a legitimate cause for the British to accept as a vehicle for anti-racism, though not completely and sometimes reluctantly. I felt incredibly warmed by a recent tweet and hand of comradeship from the UK arm of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement towards Palestine. And then the reaction: “It’s racist, it’s antisemitic. It will diminish their cause!”

Britain's bloody history

To describe Israel as it is - a settler-colonial state where millions of Palestinians live under military occupation and are denied the right to vote, freedom of movement and self-determination - is now described as racist. BLM is not operating within British polite society. By taking direct action and pulling down statues of slaveholders, they have sparked a necessary debate.

As a society, we are finally talking about the school syllabus and Britain’s bloody history; we are talking about racism towards Palestinians. I salute you, comrades.

The British couldn't stomach Corbyn. It seems that no one one will get into 10 Downing Street unless they are a friend of Israel

The negative reaction to the BLM tweet is a slap in the face to the Palestinian voice. Starmer’s sacking of Long-Bailey is a slap in the face. Her previous pledge to Zionism during her leadership campaign was also a slap in the face. They all know that they must buy into the Zionist creed; they must not upset Israeli sensitivities, and if that means ignoring Palestinian sensitivities, so be it.

As long as calling out racism against Palestinians is branded as antisemitic, many Jews around the world will be tarnished with the responsibility of Israel’s actions. In this dizzying circle, let’s remember that by definition, Palestinians are also Semites. Wiped off the map, they are a traumatised people in need of a homeland in a world that won’t accept them.

As someone of Palestinian heritage, I grieve Corbyn as probably the last possible prime minister who would back the Palestinians. As a British citizen, I’m pragmatic and want to see a Labour government, and a better Britain where thousands of vulnerable people are not killed each year through austerity.

The British couldn’t stomach Corbyn. It seems that no one will get into 10 Downing Street unless they are a friend of Israel. We may get a centre-left government, but its foreign policy will be mired in filth, supporting dictators, wars and occupation. We’ve been here before, with Tony Blair’s Sure Start centres and countless dead in Iraq. This, along with Starmer, the British find easier to stomach.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].