Trojan Horse, Prevent, Islamophobia: How the EHRC failed British Muslims

In an interview with Middle East Eye last month, the former Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn launched a pointed attack on the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

Asked about the equalities watchdog’s ongoing investigation into Labour antisemitism allegations under his leadership, Corbyn said that the EHRC was “part of the government machine”, adding that its independence had been “taken away” by the ruling Conservative Party.

This is a serious claim because it suggests that the EHRC is not doing the job it was set up to do, namely protecting the rights of people in vulnerable communities.

If Corbyn is right, then the EHRC is failing in its duty. It is protecting the government rather than those subject to discrimination. In this article we set out to examine Corbyn’s claim.

In the beginning

The EHRC was established in 2006 under Tony Blair's Labour government as a “non departmental public body”. It describes itself as independent of government, though it says it “works with government to influence progress on equality and human rights”.

It grew out of the Commission for Racial Equality - a longstanding object of contempt and mockery from the right-wing press and publicity-seeking Conservative politicians - which had been established in 1976 following a series of race relations acts passed in the light of changes to citizenship rules.

The latter had reduced the rights of non-white Commonwealth citizens who had migrated to the UK, something that has now returned to haunt the country in the form of the Windrush scandal.

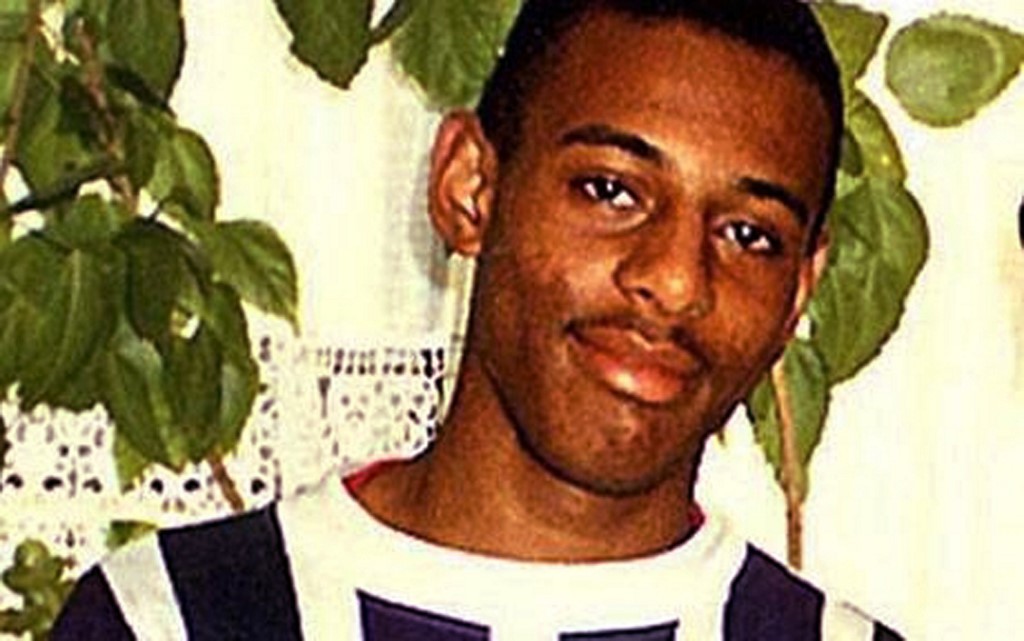

Urgency to the work of the commission was added by the 1999 Macpherson Report into the death of Stephen Lawrence, a Black teenager murdered in London, and its finding of institutional racism in the capital's Metropolitan Police force.

Labour’s initial approach to addressing equalities concerns was to set up a series of commissions addressing issues such as gender and disability rights.

In 2007 these were merged into a single commission, the EHRC.

Before the 2010 general election, the Labour government proposed a new Equality Act, extending protections against discrimination to other “protected characteristics” - age, gender re-assignment, marriage or civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, sexual orientation, and religion and belief.

These would also be part of the remit of the EHRC.

Conservative politicians and press were suspicious of these developments. Human rights legislation was frequently blamed for failures to deport criminals or ban alleged extremists.

It was surprising, then, that the new Conservative-dominated coalition government led by Prime Minister David Cameron committed itself to passing the Equality Act 2010.

However, it did so with the EHRC beset by financial and governance difficulties and the government seeking to reduce expenditure as part of its austerity programme.

This included a so-called "bonfire of the quangos", with the EHRC included in the review of arm’s length bodies under the Public Bodies Act 2011.

The EHRC emerged with a considerably reduced budget and a requirement for onerous bi-monthly meetings with the responsible minister. Its annual budget was slashed by 68 percent and subject to Cabinet Office spending approval.

The EHRC at present does not have a single Black commissioner, nor apparently any from a Muslim background

At the same time, commissioners were recruited from those with expertise (e.g. from among former civil servants and businesspeople) rather than experience (e.g. from among civil society groups active on equalities). It also increased the number of commissioners with links to the Tory party.

This may help to explain why the EHRC at present does not have a single Black commissioner, nor apparently any from a Muslim background. When we asked the EHRC about this, a spokesperson said that religion was a private matter, and pointed out that the current chair, David Isaacs, had said that the organisation would like a more diverse board.

These measures laid the ground for greater political control.

But let’s first make a philosophical point.

Different agenda

Human rights are usually understood as favouring respect for difference and, thus, for multiculturalism within a liberal framework.

This was the position of the Runnymede Trust’s Commission on the Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain under Bhikhu Parekh, a former vice-chair of the Commission for Racial Equality, which reported in 2000.

It argued that national identity should be understood as inclusive of ethnic minorities and should express their right to co-determine the political community to which they belonged.

But Trevor Philips, the first chairman of the EHRC (and himself a former chairman of the Runnymede Trust, which had commissioned the Parekh report and chaired its launch), had a different agenda.

Philips was concerned about the expression of religious difference by Muslims. By 2005 he was arguing that Britain was “sleepwalking our way to segregation.” The Labour government was expressing similar concerns.

Then in 2009, on the 10th anniversary of the Macpherson report, he criticised its central idea of institutional racism. He argued that the phrase obscured a decline of racism in Britain, which was one of the “best places in the world to be an ethnic minority”.

When we put it to Phillips that he had a different agenda to Parekh and reminded him of these comments, he told us: “I do not assent to any of the premises of your questions.”

When David Cameron declared, at the 2011 Munich Security Conference, that “state multiculturalism” was dead and that many British Muslims were living segregated lives with values at odds with those that underpinned public life in the UK, Phillips - then still director of the EHRC - once again agreed.

There was no evidence for this claim, which has been contradicted by the government’s own citizenship surveys since the argument was first put forward following urban unrest in northern towns with large Muslim communities in 2001.

These have shown consistently that British Muslims show exceptionally strong commitment to the liberal underpinnings of public life, not least because they are beneficiaries of religious tolerance.

But there was no defence of Muslims from the EHRC in the aftermath of that Munich speech. This failure was particularly striking since “religion and belief” had become protected characteristics in the 2010 Equality Act.

Then the EHRC’s own Fairer Britain reports found that Muslims were the most disadvantaged religious minority in Britain. Another EHRC report attributed this disadvantage to “skin colour” and the false perception that they are culturally and religiously “alien” to the mainstream culture.

Staggeringly, the EHRC did nothing to address this by taking, or recommending, positive action to address these issues.

The Trojan Horse

More shocking still has been its failure to act over the Trojan Horse affair, which burst into the news in early 2014 with claims about Islamist extremism in Birmingham schools.

This involved deeply flawed government reports and, finally, in 2017, the collapse of professional misconduct cases brought against teachers at the school at the centre of an alleged plot.

The cases collapsed because of “serious improprieties” on the behalf of lawyers acting for the agency of the Department for Education responsible for teacher standards.

If ever there was a scandal which cried out for a full-scale investigation by the EHRC, it was Trojan Horse.

Instead, in the wake of the affair, the government ratcheted up its Prevent counterterrorism strategy to address “non-violent extremism”.

This was a crucial moment in the government’s relationship with Muslim citizens.

The revised Prevent strategy allowed “public interest” in security to trump the right to protection of religious expression on the part of British Muslims.

Supporters of Prevent are entitled to say that freedom of expression is demonstrated by the country’s mosques, Muslim organisations and charities, and, by comparison with some other European countries, the lack of a ban on face covering.

However, critics of Prevent are concerned with the clumsy and often implicit conflation of Islam as many choose to practice it with extremism, and its consequences for public perceptions of Muslims (including within the Tory party and its problems with Islamophobia).

Yet the EHRC had nothing to say about this, even though the issue was squarely within its remit.

We have detected a pattern of silent assent on behalf of the EHRC to government policy.

Here’s another example.

In 2016 two parliamentary committees, the Committee on Women and Equalities and the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights, called for a review of Prevent over concerns it was discriminatory against Muslims.

Once again, the EHRC was silent – which made it easier for the government to fail to react.

Instead Prime Minister Theresa May proposed in her 2017 Conservative manifesto that “equalities” should be used as part of an extended counter-extremism strategy.

“Extremism”, she stated, “especially Islamist extremism, strips some British people, especially women, of the freedoms they should enjoy, undermines the cohesion of our society and can fuel violence. To defeat extremism, we need to learn from how civil society and the state took on racism in the 20th century.”

In the aftermath of the election she duly set up the Commission for Countering Extremism which has characterised the expression of conservative religious views or political Islam, alongside manifestations of far right and far left ideologies, as involving "hateful extremism".

This was another matter of intense relevance to the EHRC. But yet again the organisation said nothing about religion and belief as a protected characteristic.

Instead, it has declared that one of its priorities would be to ensure “the education system promotes good relations with others and respect for equality and human rights”, as if this might be in doubt in some publicly funded schools, when its own reports found no evidence that it was.

The EHRC was again largely silent throughout the wide and negative reporting about protests by Birmingham parents concerning LGBTQ teaching in primary schools, in which many of the children were from Muslim backgrounds.

In its only intervention, David Isaac, the chair of the EHRC since 2016, told the Independent newspaper that headteachers of primary schools should be free to teach children about LGBTQ relationships without consulting parents.

But education guidelines stress the need to build “positive relationships” with faith communities. What is more, they do so by invoking the Equality Act 2010, the very piece of legislation which sets the terms of reference for the EHRC.

The Department for Education’s guidelines cite religion and belief as a protected characteristic: “A good understanding of pupils’ faith backgrounds and positive relationships between the school and local faith communities help to create a constructive context for the teaching of these subjects…

“Schools must ensure they comply with the relevant provisions of the Equality Act 2010, under which religion or belief are amongst the protected characteristics. All schools may teach about faith perspectives.”

The battle over Islamophobia

Since a landmark Runnymede report on Islamophobia in 1997, Muslim organisations have sought to establish a formal definition, similar to that for antisemitism.

There has been a determined effort to block such a development by lobby groups such as the Henry Jackson Society and Policy Exchange, as well as the National Secular Society.

Where, one might ask, does the EHRC stand on this issue, which falls squarely within its sphere of responsibility?

Once again, it has ducked the question.

It has refused to say whether it thinks a formal definition of Islamophobia would be helpful to address the discrimination its own reports show is faced by British Muslims.

It resisted pressure to investigate charges of Islamophobia in the Tory party. When the prime minister finally set up an internal investigation, it declared “it would not be proportionate” to initiate its own investigation.

This, in spite of the fact that a YouGov poll last year unveiled the chilling finding that two-thirds of Tory members believed parts of Britain operated under sharia law. Almost half believed in the myth of no-go zones where “non-Muslims are not able to enter”, while 39 percent thought Islamist-inspired attacks “reflected widespread hostility to Britain among the Muslim community”.

We now turn again to the hugely controversial Prevent strategy. We asked the EHRC whether it had made a submission to the Independent Review of Prevent that is currently in progress, but had a deadline for submissions by 9 December last year.

It replied that it had not done so.

This is extraordinary given that the organisation has acknowledged strong views on Prevent.

We know this because it has stated them in its annual reports to the UN. Indeed, its last report in March 2020 could hardly have been stronger.

It highlighted concerns “that Prevent is discriminatory and risks undermining freedom of speech, the right to private life and the right to manifest a religion.”

It is obliged to make this report to the UN, which accredits national human rights institutions under the Paris Principles of 1992, and where the EHRC enjoys an A-Rating.

The question arises why the EHRC should tell the United Nations about concerns over Prevent - but keep quiet about those concerns when it comes to the Independent Review of Prevent.

'Structural race inequality'

It cannot be stressed too strongly that the EHRC has a constitutional duty to support and uphold the obligations of the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Equality Act 2010 to protect the freedoms of British citizens.

This continuing duty and the powers to conduct inquiries were set out explicitly in the Equality Act 2006.

The duty included “encouraging and supporting the development of a society in which… there is mutual respect between groups based on understanding and valuing of diversity and on shared respect for equality and human rights.”

For a body charged with tackling discrimination, the EHRC has arrived embarrassingly late at fundamental issues confronting our society. It has recently announced an inquiry into the impact of coronavirus on BAME communities which, it says, has revealed "long-standing, structural race inequality" in Britain.

This investigation, while commendable, raises the question why the EHRC didn't react to issues of “structural race inequality” in Britain earlier. Following Wendy Williams’s review of the Windrush scandal, it has announced an assessment of hostile environment policies at the Home Office.

Bear in mind that the Guardian journalist Amelia Gentleman and politicians from Caribbean nations were raising the issue in 2018. Amber Rudd resigned as home secretary in April of that year. MPs were calling on the EHRC to investigate in April 2019.

Sadly, the EHRC has also repeatedly failed to speak up for the rights of Britain’s Muslim citizens. This means that there is some justice in Jeremy Corbyn's criticism, irrespective of the outcome of its well publicised inquiry into alleged Labour antisemitism.

We have made many material criticisms of the EHRC in this article. We put all of them to the EHRC in good time before publication. The EHRC has chosen to avoid answering any of them.

Instead a spokesperson issued us a blanket assertion:

“We have a strong track record of working to make Britain a fair society in which everyone has an equal opportunity to fulfil their potential and participate, without being limited by prejudice or discrimination.

“We take our independence and impartiality incredibly seriously. To suggest otherwise fails to acknowledge our past and ongoing work in holding government to account and promoting equality and human rights across a range of issues, including work on religion and belief and racial inequality.

“As set out in the Equality Act, commissioners are appointed by the government of the day. All our board members bring a wealth of experience and have a strong track record of working on equality and human rights and corporate issues. Robust policies and procedures are in place to manage any perceived conflicts of interest.”

We disagree. The truth is that on Black and Muslim issues the EHRC has served the government’s agenda. It has repeatedly failed to display the teeth or the will to tackle the key issues that ought to have been on its agenda for the past decade.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].