How Israel’s archaeological excavations work to rewrite history in Jerusalem

Holding a hammer in his hand, United States Ambassador to Israel David Friedman broke ground during the inauguration of the "Path of the Pilgrims" tunnel in June 2019.

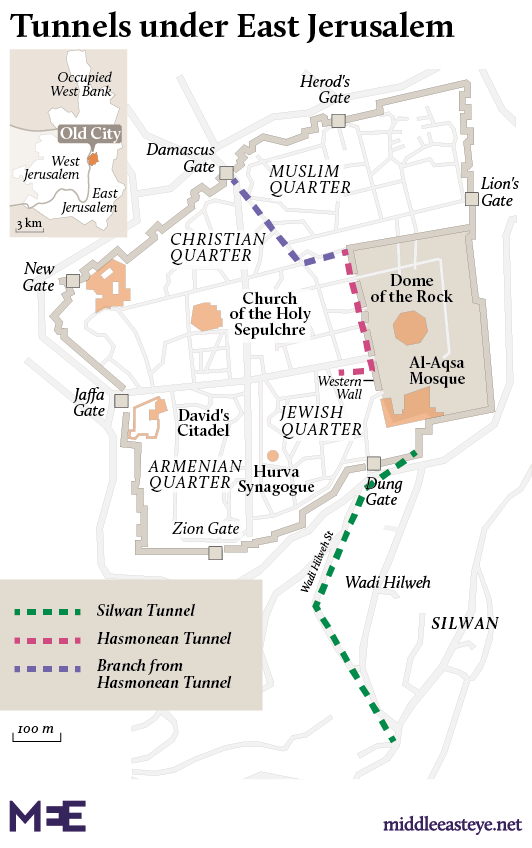

Just south of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in occupied East Jerusalem, the tunnel - about 850 metres long and eight metres wide, runs just three to four metres beneath the homes of Palestinian residents of the Wadi Hilweh neighbourhood of Silwan, a Jerusalem-area town.

The government-funded project, part of the larger "City of David" Israeli tourist project, is being led by Ir David (also known as El-Ad), a private Jewish settler organisation, with the excavations carried out in cooperation with the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Israel claims the excavations below Silwan and the Old City of Jerusalem are aimed at unearthing traces of the three-millennia-old First and Second Jewish Temples, which Jews believe to have been built where the Al-Aqsa Mosque now stands. To date, Israel has invested at least 40 million shekels ($11.7m) in the initiative.

The archaelogical project, however, has become a subject of global controversy and yet another source of suffering for Palestinians.

With at least 45,000 Palestinians living in Silwan, many have highlighted that the "City of David" project and other archaeological digs are part and parcel of Israel's efforts to strengthen its physical and political hold over the neighbourhoods lining Jerusalem's Old City, and to cement the position of the more than 400 Jewish settlers living in Silwan, in violation of international law.

Pushing a Zionist narrative

Just as the "Path of the Pilgrims" was unveiled last year, Israel's former mayor of Jerusalem Nir Barakat said anyone visiting the tunnel "knows exactly who the landlord of this city is".

Descending into one of these tunnels, visitors are surrounded by signs representing what would have once existed there. But while Jerusalem has a long, culturally and religiously diverse history, the information conveyed in the tunnels focuses exclusively on the city's Jewish history.

Illuminated screens show three-dimensional models of the Jewish temple structure, and a colourful cartoon of workers building the temple and dragging its stones.

Some paper scrolls bearing verses from the Torah are also tucked into glass racks, and miniature topographic structures are on display.

The tunnels have been fitted with significant infrastructure, turning them into an underground city with cement-clad walls, iron support structures and air conditioning. They also include prayer and ablution points, as well as spaces for religious ceremonies and conferences.

In 2018, a European Union report leaked to the Guardian newspaper said Israel was developing archaeological and tourism sites to legitimise illegal settlements in Palestinian neighbourhoods of Jerusalem. The report said such projects were being used "as a political tool to modify the historical narrative and to support, legitimise and expand settlements".

"East Jerusalem is the only place where Israeli national parks are declared in populated neighbourhoods," the report read, pinpointing the "City of David" project as part of an intentional "narrative based on historic continuity of the Jewish presence in the area at the expense of other religions and cultures".

It went on to criticise private settler organisations which it said were "promoting an exclusively Jewish narrative, while detaching the place from its Palestinian surroundings". Reports by the United Nations have also echoed such concerns over the years.

'Bad archaeology'

The large-scale excavations began in 1967 under the auspices of Israel's Ministry of Religion, shortly after that year's Middle East war.

The first tunnel that was dug, dubbed the "Hasmonean Tunnel", is 500 metres long and located on the western side of the al-Aqsa Mosque, where the Moroccan Quarter of Jerusalem's Old City once stood. Straddling the Western Wall, the neighbourhood was demolished by Israeli authorities in its entirety three days after Israel captured East Jerusalem.

Abdel-Razzaq Matani, a Jerusalem-based archaeology researcher, told Middle East Eye that the exact number of tunnels dug under the al-Aqsa Mosque compound and the Old City remains unknown. Israeli authorities only make announcements about certain tunnels, he said, while barring any outside archaeologists or surveyors from studying the area.

According to Matani, the topography of Old Jerusalem consists of several layers below the ground. Each period saw the building of homes on the arches of the older homes, aided by the natural valley landscape of the space, until many layers were formed over the original layer of rock.

The majority of the tunnels were originally dug during the Hellenistic, Crusader and Islamic periods, and were used as waterways or passages that were subsequently buried as more construction was built above.

While the narrative promoted while walking through the "Western Wall tunnels" today is almost exclusively about the Second Temple, archaeologists say that most of the remains in the tunnels are actually from later periods.

One such example is a historic hammam, or bathhouse, from the 14th century Mamluk era, one of the largest spaces inside the tunnels. Israeli NGO Emek Shaveh, which addresses the politicised nature of Israel's archaeological digs, has highlighted how the space's focus on the story of Jewish pilgrimage to Jerusalem has in effect been "completely ignoring the historical significance of the site".

The experience of the tunnels "reinforces a Jewish religious narrative", the group wrote.

Beyond engaging in historical revisionism, archaeologists have accused the Jerusalem tunnels project of blatantly disregarding basic techniques of the trade.

Matani asserts that while the current archaeological digs are being carried out in a horizontal manner, the correct way to do it, so as not to harm the historical layers, is in a vertical manner, from the surface downwards.

The current horizontal excavations have also been identified as problematic by Emek Shaveh and senior officials at the Israel Antiquities Authority, who called it "bad archaeology".

Inside the tunnels, one can see the foundations of the Al-Aqsa Mosque uncovered due to the excavations.

Emek Shaveh has stressed that Israeli excavations are being used as a means to justify Israeli settlement in Silwan and as a tool for political ends, threatening the diverse social and cultural fabric of Jerusalem.

Damaged homes, endangered people

Over the past few years, the digging has caused severe structural and foundational damage to Palestinian homes, particularly in Silwan, experts say.

In 2017, a group of 25 residents were forced to leave their homes in the town due to such damage making the buildings unsafe to live in.

The tunnels have also started to constitute a major threat to the foundations of the Al Aqsa Mosque compound.

Most of the tunnels are concentrated below the western ramparts of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound and the Western Wall - known to Muslims as the al-Buraq wall - and below the Umayyad palaces south of the mosque, extending to the centre of Silwan.

Researcher Najeh Bkairat told MEE that the tunnel network branches out and extends to the Al-Qarmi neighbourhood, west of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City, as well as to the east and north near Damascus Gate, along with southern branches reaching Silwan.

The consequences have been severe, Bkairat said, causing cracks in large buildings, and affecting the foundations of 16 Islamic monuments along the route.

According to the Silwan-based Wadi Hilweh Information Center, due to the recent excavations, the area of Ein al-Hilweh has suffered landslides, with ground in playgrounds, parking lots, and lands belonging to the Greek Orthodox Church collapsing. Damage to infrastructure has become more severe during the winter season at times of heavy rain.

Bkairat says that, overall, the structures most affected by the digging are in the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, particularly the al-Marwani Prayer Hall, and cypress trees whose roots have been damaged.

Not only have excavations resulted in cracks and collapses in historic buildings west of Al-Aqsa, but a number of tombs have also been affected and have been sliding downwards, the researcher said.

Since the start of excavations, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) has called on Israel to halt its digging, stressing the illegality of such actions in occupied territory.

Israeli excavations were halted only for several months in 1974, after Unesco suspended all aid to Israel. Later that year, the historic Jawahiriya school west of the Al-Aqsa mosque compound collapsed.

In 1996, then-newly elected Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu opened an entrance to the "Western Wall tunnels" adjacent to the al-Aqsa mosque compound, unleashing Palestinian protests during which Israeli forces killed some 80 Palestinians.

As US President Donald Trump has provided unmitigated support to Netanyahu, recognising all of Jerusalem as the undivided Israeli capital in 2017, Palestinians fear that efforts to "Judaise" the city will continue to accelerate.

With Silwan residents caught in lengthy battles against eviction, the struggle - both above and below ground - continues.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].