Egypt is cracking down on women's freedoms on and offline. But they are fighting back

The jailing of five Egyptian influencers on charges of "violating public morals" over videos they published on TikTok has set a new precedent for controls that women face online, as well as the social limits increasingly placed upon them.

But though the internet is now apparently a place unsafe for Egyptian women to express themselves, it is also a platform where they are rallying - both to defend those convicted over their TikTok posts and to raise awareness for abuse meted out to them by men.

On Monday, five young women were sentenced by a court to two years in prison and each fined 300,000 Egyptian pounds ($18,750). Their alleged crime was to publish content that was morally problematic for the public and Egyptian family values.

The content, however, would seem to many as innocent and innocuous and has raised alarm bells for both women's rights activists and proponents of free speech.

'These women were simply being targeted for being women who dare to be different or autonomous'

- Reem Abdellatif, journalist

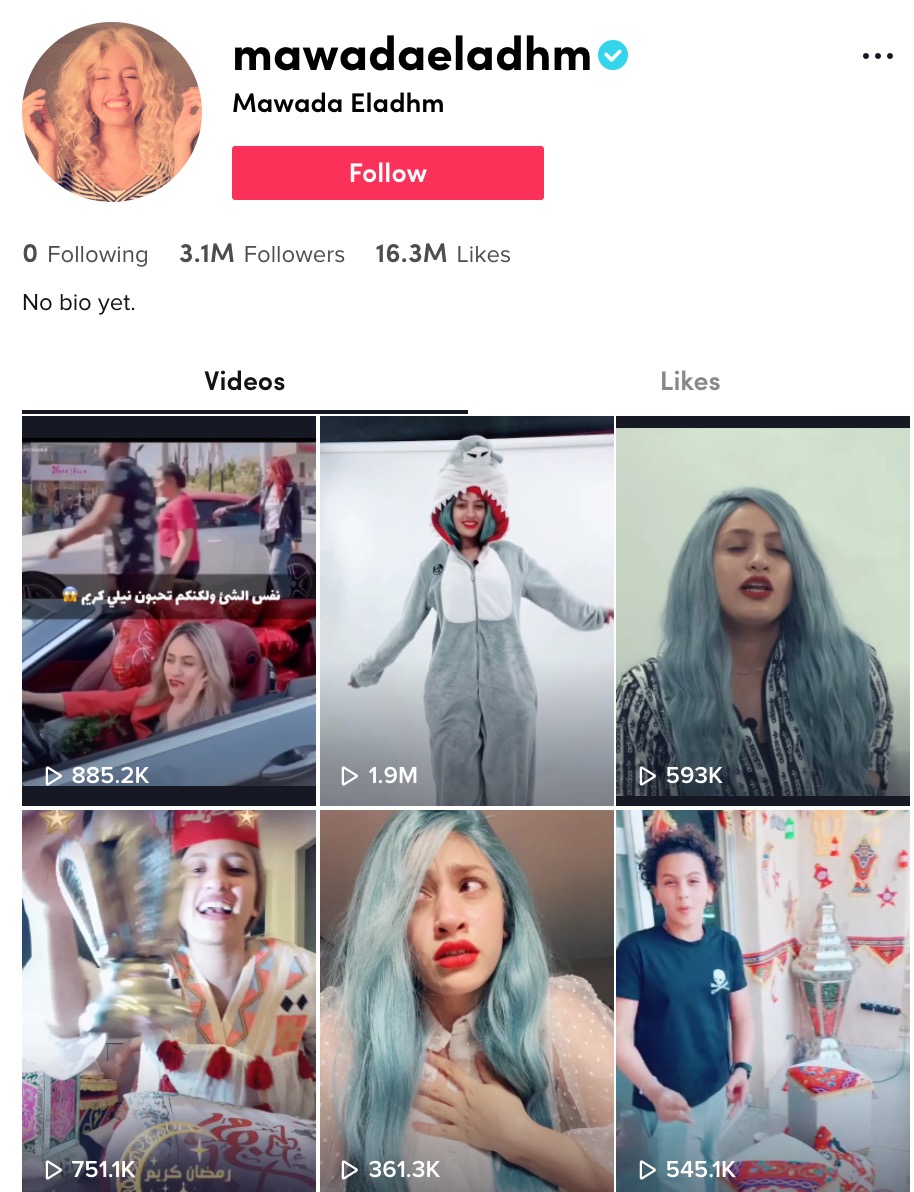

One of the women, Mowada al-Adham, used the app to share a video with her three million followers of the influencer dancing, lip-syncing and posing in a convertible car while listening to music.

Another, Haneen Hossam, who has a following of one million, uploaded footage detailing how others could use the app to earn money.

The videos are reminiscent of many of the trends TikTok users around the word take part in, including comedy sketches and voiceover skits. However, the Egyptian authorities' response has been swift and severe.

According to Egyptian media, Adham was asked to submit to a virginity test which was requested for the investigation, but refused to do so. The United Nations has previously called for a ban on virginity testing, which violates human rights and can cause pain, health issues and trauma.

Reem Abdellatif, an Egyptian-American journalist who has previously used social media to campaign for women's empowerment and education, said women in Egypt were afforded little freedom of speech, especially those who come from the working class.

“It is unfortunate but common for vague and loosely worded laws to be constantly used to repress women and sometimes activists in Egypt … These women were simply being targeted for being women who dare to be different or autonomous,” she told Middle East Eye.

“Women and girls in Egypt are still struggling to have their basic rights, such as bodily autonomy and personal freedoms, but working class women from low-income backgrounds struggle with this for more obvious reasons.”

Much of the backlash against the influencers has come from Egypt's state-backed media.

In a teary video posted to Instagram in April, days before the five were arrested, Hossam said the media had taken her content and shared it out of context, claiming that what she is doing is inappropriate.

She said many do not understand how people can make money through social media, and stressed it is no different from presenters and public figures earning a living on TV.

“Rumours have ruined lives. I have never said anything bad in my videos, I never said I wanted girls to do inappropriate things to earn money. I said respectable girls could earn money on social media. No one works without getting paid in return, so how is this different?” she said.

In another video, which has been viewed over 800,000 times, Hossam added that she had been on the receiving end of an onslaught of harassment, which had caused her significant distress.

“What are you benefiting from by destroying someone? Beating someone when they are down is wrong… there are people doing much worse things, why are people focussing on me? Bloggers are not hurting anyone, why are people creating rumours with no evidence?” she said.

According to Amr Magdi, a Middle East researcher at Human Rights Watch, the recent wave of arrests reflect the current state of the country, which is heavily monitored and censored by authorities.

Since the 2013 military coup that brought President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to power, human rights abuses have skyrocketed. Tens of thousands of Egyptians accused of being critical of the government have been imprisoned under Sisi.

Social controls are becoming ever more prevalent and punitive.

“It’s very concerning and it’s an abusive campaign of arrests and persecution mainly of women and girls, based on what they wear and how they behave… it shows what direction the country is heading in,” Magdi told MEE.

“The Egyptian law is very vague and broad. They talk about acts which undermine family values, but the law does not define what these acts are, so citizens do not know when they are violating the law," he added.

"The punishments for these acts are also extremely disproportionate. It can be up to five years in prison, or sometimes more, with large fines.”

All five of the TikTok influencers were prosecuted under Egypt's 2018 cybercrime law, legislation that has been widely criticised by human rights campaigners and activists for being vague and used to unfairly target people.

Not only can authorities imprison and fine people for content posted online deemed to be inconsistent with family principles or the values of Egyptian society, the law allows any social media accounts with more than 5,000 followers to be monitored.

Like Abdellatif, Magdi believes that the recent wave of arrests have unjustly targeted people from lower social classes, suggesting that the government allows wealthy Egyptians to behave in certain ways, but not the general public.

'What these women did you can see every day on TV and in high-class resorts, beaches, but no one goes there to arrest them'

- Amr Magdi, HRW

“This perpetrates another type of discrimination against social economic status, because what these women did you can see every day on TV and in high-class resorts, beaches, but no one goes there to arrest them,” he said.

The arrests have brought into question what the Egyptian government perceives as public morals and the role of women in Egyptian society. Magdi described the message being sent to society as "deeply chilling and frightening", predicting more crackdowns to come.

“We have seen Sisi himself talking about women in derogatory ways on several occasions, for example the role of women at home and how they should support their families and husbands at home,” he said.

Under Sisi, the Egyptian government has seized close control of the country's media. Not only does it heavily regulate how outlets are run, the government also influences the way people are presented in films and the arts.

“Egyptian intelligence has moved to monitor and monopolise the media. One of the motives behind this has been to dictate how women should behave and look in TV dramas," Magdi said. "There are many indications that there is a coordinated effort by actors in the government to oppress women and strip women of some of their rights.”

Women fight back

With traditional media closely regulated and street protests non-existent after the government's deadly crackdown on Egyptians demonstrating against the 2013 coup, women have been forced to turn their discontent online.

Activists and social media users have been using the hashtag "If the Egyptian family allows" to decry women's treatment and highlight the ease with which they can be arrested on such charges.

Meanwhile, a petition has been started online, where over 2,800 people have signed to call for authorities to stop targeting women on TikTok, and for the National Council for Women to provide legal support for the women currently detained.

The petition questions what the “family values” that are allegedly being violated are, and denounces the authorities for targeting and detaining women.

“We fear and worry about this systematic crackdown which targets low-income women. We can't ignore the underlying guardianship over TikTok women. Because of their class, they are being punished and denied their own right to their bodies, to dress freely and to express themselves," the petition states.

Social media has taken particular prominence for Egyptian women in recent weeks, as thousands have used the platforms to highlight harassment and sexual assault, in what has been called Egypt’s #MeToo movement.

Waves of allegations and accusations have flooded social media, with women calling out their harassers and demanding for them to be held accountable.

'The online space has become almost unsafe for women, ironically, who are utilising social media to create awareness and press for change'

- Reem Abdellatif, journalist

It has shown that online pressure can work. The outpouring of accusations and solidarity online prompted an anonymity bill to be passed in Egypt, allowing victims of abuse to have their identity protected.

The bill came days after authorities arrested a 22-year-old who was accused by around 100 women of sexual crimes, including blackmail, rape and online sexual harassment.

That being said, as the TikTok case shows, the internet is far from a safe space for women. Recent reports show that women in the Middle East and North Africa region are facing increased harassment and abuse online, with little legislation to protect them.

According to Abdellatif, women in Egypt and around the Middle East are being targeted for the messages they post online, particularly when they go against societal norms or a patriarchal society.

“The online space has become almost unsafe for women, ironically, who are utilising social media to create awareness and press for change," she said, adding that abuse has intensified in recent weeks due to the Egyptian MeToo movement and the coronavirus lockdown.

"What happens online is very similar to what happens offline: systemic silencing of women who dare go against the grain, or simply have an opinion that is independent of society's misogynistic mainstream teachings.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].