Hajj 2020: Is it time to rethink how the pilgrimage is organised?

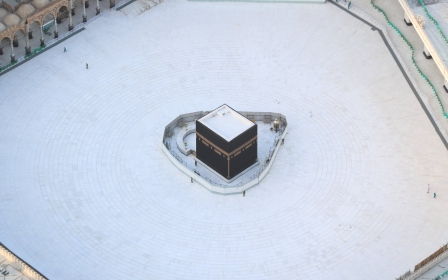

Hajj - the annual Muslim pilgrimage - has begun, but nearly all of the 2.5 million people who had planned to go this year have been relegated to watching the colossal event from the sidelines.

One of the five pillars of Islam, the Hajj is an obligation for all financially and physically able Muslims at least once in their lifetime.

But this year, only 10,000 people - all residing in Saudi Arabia - will be able to participate in the five-day pilgrimage, a fraction of the number who attended last year.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, around 11,000 American Muslims usually take part in the pilgrimage - but spiralling costs and a reported lack of communication from Saudi authorities during this year's preparations has led some to call for a reorganisation of the event.

"Hajj is a big money industry in America," Hamzah Wald Maqbul, an imam at the Islamic Center of Cleveland in Ohio, told Middle East Eye.

The pilgrimage can range in cost from $6,000 all the way to almost $14,000 for US pilgrims - a substantial figure when compared with Indonesia, the world's largest Muslim-majority country, where the average cost is closer to $2,000, according to the country's ministry of religious affairs.

"With all the big Hajj tour operators [in the US], it seems that the religious aspect is almost an afterthought, or at best a secondary consideration," said Maqbul, who has been on the pilgrimage six times, several of which as tour leader.

"[In the industry] there are a lot of people engaging in unscrupulous behaviour, people who cheat, people who are just incompetent."

'Better-coordinated communication'

Following Saudi Arabia's decision to host a scaled-down pilgrimage due to the pandemic, several tour operators told MEE that a lack of communication from Riyadh had caused severe financial strain to operators and would-be pilgrims alike - with airlines and hotels in the kingdom deferring booking dates rather than issuing refunds.

"Given the unprecedented late cancellation of millions of Hajj packages in 2020, business relations between suppliers and customers along transnational pilgrimage chains will undoubtedly be fraught for months, and potentially years," said Sean McLoughlin, a researcher in Hajj and professor of anthropology at the University of Leeds.

"What's needed is more effective self-governance by the pilgrimage industry, and more transparent and better-coordinated communication between pilgrims, travel companies, as well as Saudi and other authorities," McLoughlin said on Tuesday during a webinar organised by George Mason University.

"The lack of professionalism and compliance among some Saudi-licensed Hajj organisers is exacerbated by inconsistent approaches to regulation and enforcement"

- Sean McLoughlin, University of Leeds

According to several of the tour groups, a lack of communication from the kingdom over next year's Hajj has renewed calls for two of Islam's holy sites, Mecca and Medina, to be placed under international oversight.

"The fallout of Covid-19 will magnify challenges that the Muslim pilgrimage industry was already confronting," McLoughlin also wrote in The Conversation.

"The lack of professionalism and compliance among some Saudi-licensed Hajj organisers is exacerbated by inconsistent approaches to regulation and enforcement."

Earlier this year, Al Haramain Watch, a non-governmental organisation, launched an online petition calling for a "unified Muslim administration from all Muslim countries" to manage the two holy cities.

The petition, which was signed by more than 100 Muslim scholars, accused Riyadh of gross human rights violations and restricting minorities' access to the holy cities.

'Tool in Saudi Arabia's foreign policy arsenal'

For nearly 100 years, Saudi monarchs have all adopted the honorary title of Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques to bolster their standing in the Muslim world.

While the kingdom has received credit for its management of the pilgrimage and the welfare of millions who descend upon the country each year, the ruling Al-Saud family has also been criticised for having complete say over who attends - setting quotas for pilgrims from various countries and spiting its rivals in the process.

With the ease of air travel, the number of pilgrims performing Hajj has skyrocketed from 100,000 in the 1950s to around 2.5 million today.

Since the 1990s, the kingdom has imposed a quota system, with the number of would-be pilgrims from each country capped relative to the size of its Muslim population.

Turan Kayaoglu, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Doha Center, says the Hajj has become "one more tool in Saudi Arabia's foreign policy arsenal".

"The kingdom chooses to keep the quota system as opaque as possible in order to exploit it as a political tool to reward its allies and punish its adversaries," said Kayaoglu, who is also a professor of Politics, Philosophy & Public Affairs at the University of Washington Tacoma.

In 2015, after a stampede and crush of pilgrims killed at least 2,426 people, Iran, which lost 464 pilgrims, immediately called for an independent body to take over administering the Hajj.

The following year, Iranians were excluded from attending. In 2018, a year after Saudi Arabia and three other Arab countries cut all diplomatic and transport links with Qatar, Qatari nationals were restricted from performing the sacred duty.

Profit over pilgrimage

Maqbul says the industry prioritises profit over the pilgrimage, and consistently prevents low-income families from attending.

He said the potential surge in demand for next year's pilgrimage may drive up costs even further.

'There's been a little bit of pain, but if anything, it's reinvigorated the spirit of the Ummah [Muslim community]'

- AbdulNasir Jangda, Qalam Institute

"There are a lot of Hajj groups that are going to take a financial hit in not being able to go. And I don't think that's necessarily a bad thing," he said.

"If it shakes some people up and throws some unscrupulous people out of business, I'm not sad about that."

Meanwhile, AbdulNasir Jangda, the founder of Qalam Institute, an Islamic seminary in Texas, said the inability for Muslims to go this year seemed to have "reinvigorated" some in his community.

"There's been a little bit of pain, but if anything, it's reinvigorated the spirit of the Ummah [Muslim community]," he told MEE.

"People are talking about that when the pandemic is over instead of like going to Hawaii for vacation, we're going for Umrah."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].