China's avoidance of Middle East conflicts may soon come to an end

How does China respond to the conflicts in the Middle East, and why? What does this tell us about China’s likely approach to the region in the future? These questions provide the basis of my new book, China and Middle East Conflicts, published last month.

The book is a counterweight to much of the recent work on China and the Middle East, which focuses on the economic dimension, including projects associated with the Belt and Road Initiative. It also differs by not only focusing on conflicts in the form of war and rivalry, but also taking historical stock of China’s relationship with the region.

Ambivalent stance

This alternative approach yields a number of insights. One is that China isn’t a new regional actor. Another is that China’s record in the Middle East has been varied, both in terms of approach and results.

At first, it embraced conflict, but then moved away from it. Today, China’s stance is ambivalent: It would prefer to avoid entanglements, but has also become involved in managing and resolving conflicts on occasion.

China has been able to stand apart from regional conflicts and rivalries because it has not been deeply involved in them. But that time may be coming to an end

China’s role towards regional conflicts may therefore be characterised in several ways: as a spoiler (where it supports or exacerbates conflict), a shirker (where it looks to avoid conflict) or a supporter of conflict management and resolution.

China’s first contacts with the Middle East occurred in the mid-1950s, when it embraced nationalist leaders and movements, including former Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Algerian National Liberation Front. It backed them in their anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggles against Western powers and Israel, providing arms or access to them.

Chinese enthusiasm for insurgent nationalist groups reached its peak in the mid-to-late 1960s, when it provided equipment and training to groups in Palestine, Eritrea and the Gulf. China’s behaviour as a “spoiler” was motivated by a shared belief that they were confronting established regional powers and regimes; for Beijing, military aid was also a way of countering and challenging Soviet primacy.

Diplomacy and commerce

Over the following decade, however, changes at home and abroad led to China downgrading its support for regional insurgencies. The end of the Cultural Revolution, the death of Chairman Mao and the rise of a more pragmatic, business-and-development-oriented leadership under Deng Xiaoping led to a less confrontational Chinese foreign policy by the end of the 1970s.

From the 1980s, China became less ambitious in its foreign policy. It increasingly prioritised diplomatic relations and commercial opportunities. That included increasing its arms sales to both sides in the Iran-Iraq War during the 1980s, even as it accused the two great powers - the US and USSR - of perpetuating the conflict. China also entered into a clandestine arms trade with Israel, which would lead to the two establishing diplomatic relations in 1992.

China maintained its “shirker” role towards conflict after the end of the Cold War. Like the rest of the international community, it embraced the Oslo process between Israel and the Palestinians, exhorting both sides to continue talking - even as the prospect of a final peace settlement became ever more remote.

Elsewhere, it opposed both Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and its resolution through force in 1991. But in contrast to France and Russia, it decided against using its UN veto as a way to challenge US hegemony ahead of the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Notwithstanding its reservations on the war, Chinese firms gained greatly in the aftermath. Many won important contracts and investments in Iraq, much to the chagrin of the Americans, who bore the financial and military costs of the occupation. Former President Barack Obama would subsequently accuse China of “free riding” on US-provided security.

Economic significance

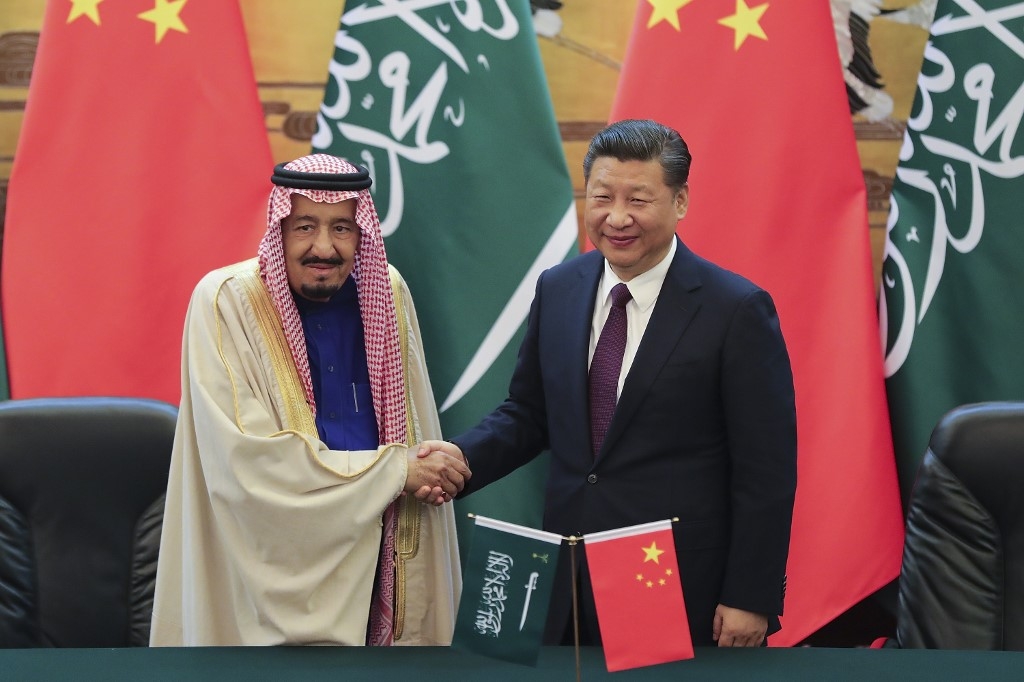

Chinese conflict avoidance has continued into the rivalries and wars of the past decade. Like most other countries, it was caught by surprise when Saudi Arabia and the UAE imposed a blockade on Qatar in 2017.

Yet, any fears that its commercial prospects might be damaged turned out to be exaggerated; both sides recognised China’s importance as a major trade and investment partner.

China’s economic significance is also evident among the warring parties in Syria, Libya and Yemen. Publicly, China appeals for political dialogue as the way to resolve differences, while demanding that Western powers stop interfering. It retains a strong commitment to state sovereignty, while also accepting the Russian and Iranian presence in Syria and that of the Saudis in Yemen.

So far, Chinese balancing hasn’t lost it any friends: Syrian President Bashar al-Assad calls China a “friend” and hopes that it will become a key financier of postwar reconstruction.

But despite Syrian enthusiasm, Chinese reticence is the order of the day, reflecting the low level of economic exchange and interests between the two countries, which is also the case in Libya and Yemen.

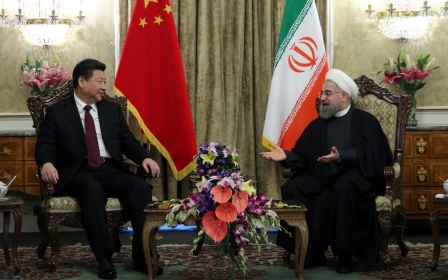

By contrast, where China’s investments are larger, it has been more supportive in managing and resolving conflicts. In response to both the Darfur crisis in Sudan and Iran’s nuclear programme, China has worked as a mediator to find compromise, prompted in part by having the ear of the two governments and for fear that western sanctions could damage its business interests in each country.

What does the future hold?

Looking ahead, it is by no means certain that the current typology of response will continue. For one, China has been able to stand apart from regional conflicts and rivalries because it has not been deeply involved in them. But that time may be coming to an end. As the Sudan and Iran cases show, it becomes more difficult where Chinese investments are deeper.

This could become the prevailing situation in the future, as China’s Belt and Road Initiative takes root. Countries across the region will find themselves competing against each other for finite Chinese capital and resources (set to become even tighter in the post-coronavirus period), while the financing and construction of such projects will tie China more closely to the region.

That may lead to China becoming less an observer of conflict, and more a cause of it instead.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].