Ancient boardgames: Experts find the missing piece (but can't figure out how to play)

It’s a curious sight inside the Batman museum, Turkey, where attention seems to be focussed on a section to the right of the main exhibition room.

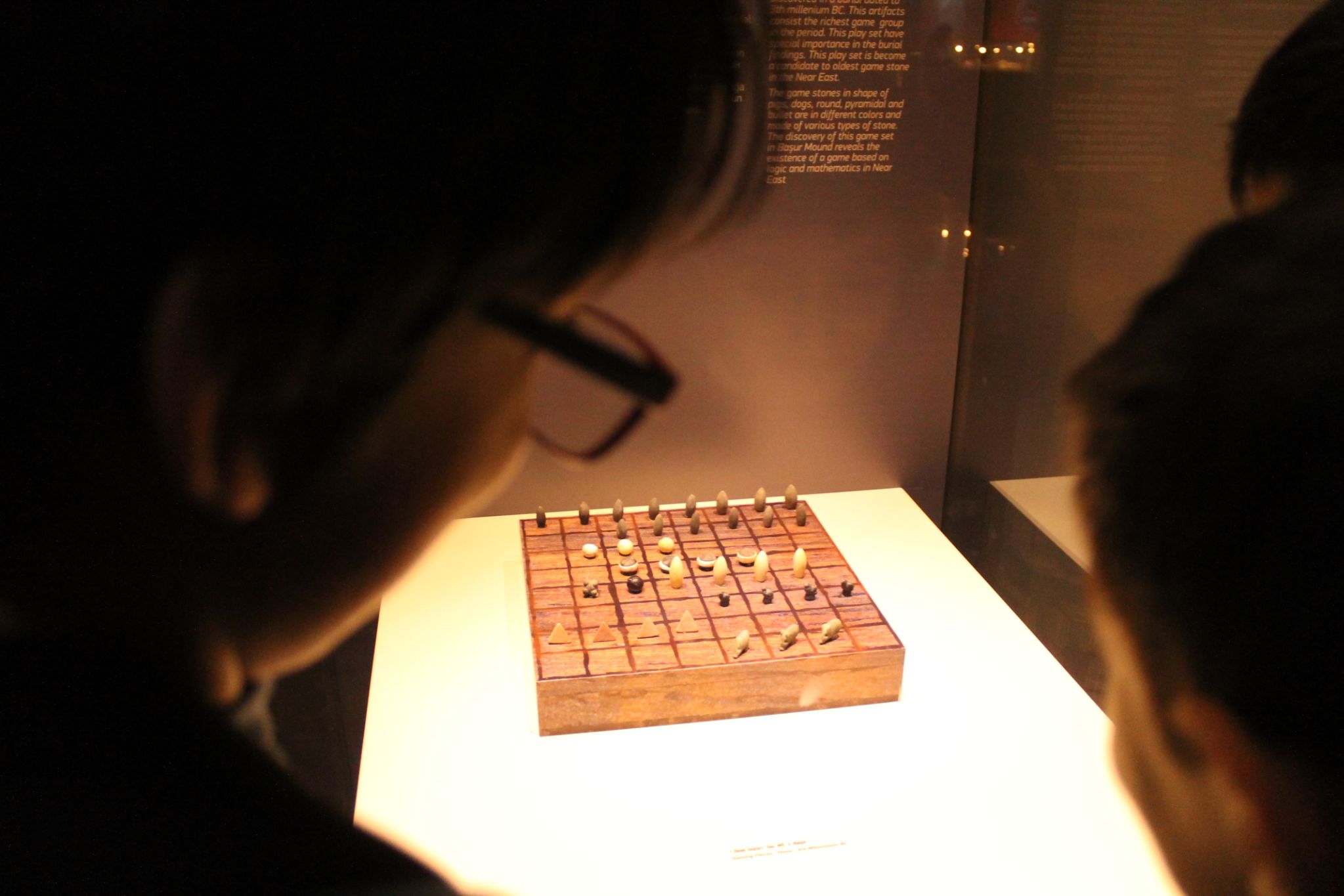

Within a glass display case in the corner, more than three dozen colourful animal figurines are presented on a chequered wooden board. Alongside the elaborately sculpted animals stand similarly tiny artefacts in various abstract and pyramid shapes.

The visitors, including a group of schoolchildren, hover in awe over the gaming pieces in the corner. They speculate over the origins, discussing excitedly the intricate connections they may have.

For 11-year-old Rasan Ekinci, a Batman local who’s been playing chess for three years, usually with her younger sister, the stones in the back rows resemble pawns from a chess board.

“But this seems more fun than chess,” Ekinci says. “I’d want to save up lots of money and buy this.”

Her school friends, meanwhile, think some of the more abstract games pieces look like burgers, trees and meteorites.

According to the museum's director, Seyhmus Genc, out of all the collections, visitors are most surprised to see these pieces. “They often ask us how the game may have been played,” he said.

“[They] are signature pieces of our museum by now. I must say they transport me to other worlds also.”

Game set

According to the carbon dating, these handcrafted pieces are around 5,000 years old.

Discovered in an archaeological site in Turkey’s south-eastern Siirt province, they could possibly represent one of the world’s oldest-known board games, sitting alongside the Egyptian Senet, Chinese Go, and Mangala, which is still played in Turkey today.

With or without the title, these items tell an intellectual, sociological story from the Early Bronze Age in eastern Anatolia - a major crossroads and corridor for trade and culture circa 3,100-2,800 B.C.

Facing the Basur Stream, a narrow basin that feeds into the Botan River on the outskirts of Siirt, Professor of Archaeology Haluk Saglamtimur and his team carried have been carrying out excavations in the hilltop Basur Mound for over a decade - no matter the weather. In the summer this often meant working in the 820ft by 492ft mound in over 40 degree heat.

'The gaming set … is nominated to be the world’s oldest and most crowded game set ever found.'

- Haluk Saglamtimur, professor of archaeology

Despite tensions caused by occasional periods of regional conflict, including the separatist Kurdistan Workers’ party’s (PKK) armed campaign against the Turkish state and the Syrian War across the border, the field phase of the project, which was carried out as part of the Ilisu Dam rescue excavations, launched in 2007 and ended in 2019, before the hydroelectric plant became active.

“[I’m] very happy we found all the pieces before excavations had to end,” Saglamtimur, who teaches at Ege University in Izmir, told Middle East Eye.

“The gaming set of 40 pieces discovered in the [Basur Mound] is nominated to be the world’s oldest and most crowded game set ever found.”

“Although they steal the show from the other findings,” he said, adding that to him the Early Bronze Age site is most remarkable because of the large number of findings in 18 tombs.

These include 80kg of metal objects (mostly copper alloy, as well as gold and silver), thousands of beads and jewellery with mountain crystals, and human bones, which hint that children were sacrificed here.

As for the game, the first 39 pieces were discovered in 2012, found buried together by one of the tombs, and were then moved to the neighbouring Batman province for public display in the museum.

In February this year, Saglamtimur announced that the game's pieces were complete - the fourth elephant figurine had been discovered in the excavations in late autumn, completing all 40 pieces.

“All but the board,” the archaeologist noted. “It must have eroded over time. We found some wooden pieces that had eroded by [the tomb]. The [board] in the museum was made for display purposes.”

‘Dogs and pigs’

Like the marble elephant, rhinoceros, monkey and crocodile from the 1995 motion picture Jumanji, where a board game takes players on an otherworldly adventure, these pieces are equally mysterious.

And the fact that the board was never found keeps everyone guessing over the rules.

Since the pieces include four pigs, four dog’s heads, four large bullet-shaped pieces, four pyramid shapes and four circular pieces, archaeologists are considering whether the game is based on fours.

There is also a piece that has lumps on the corners that Saglamtimur says could possibly have been used as dice.

“[The Basur pieces] must be a game because they were buried together, bundled by one of the 18 unlooted tombs we discovered,” he said. “They’re not used much; there’s barely any wear on them.”

The research team is welcoming suggestions from gaming enthusiasts, in the hope that they would want to help solve the mystery.

But, the professor noted, because there are many bullet-shaped pieces of different sizes and there is no particular numeric balance between them, figuring the rules of the game is no mean feat.

The research team is welcoming suggestions from gaming enthusiasts, in the hope that they would want to help solve the mystery.

Based on what they do know, the researchers have dubbed the game “Dogs and Pigs”.

“We see a similar theme when we look at the younger [games] found in Mesopotamia and Egypt: usually, two main animals inspire the game’s name,” Saglamtimur said.

One example is “Hounds and Jackals” - a pharaonic game, which is believed to have been played in Egypt around 2,000BC. In 1910, a complete set was discovered by British archaeologist Howard Carter, which can be seen today at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The function of play

Video and board games help develop intellectual, social and cognitive skills, as modern studies have regularly shown. Playing games strengthens the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex, leading to improved cognitive functions, positively enhancing IQ, memory, information retention and problem-solving.

In his popular 1944 article “Homo Ludens” (literally translated as “Man the Player”), Johan Huizinga, late professor of history at Leiden University in the Netherlands, went against tradition to argue that the notion of play has never been a byproduct of culture.

“… [It] was not my object to define the place of play among all the other manifestations of culture,” Huizinga wrote, “but rather to ascertain how far culture itself bears the character of play.”

He then delved into why humans ever play games: “The function of play in the higher forms which concern us here can largely be derived from the two basic aspects under which we meet it: as a contest for something or a representation of something. These two functions can unite in such a way that the game "represents" a contest, or else becomes a contest for the best representation of something.”

Saglamtimur says that in the case of the Basur pieces, it’s likely that a representation of strategy skills were put to a contest: “These could be the ancestors of advanced intelligence games such as chess.”

“We are highly considering that this gaming set, revealed in one of the graves where three children and one adult were buried, is a hunting, strategy and racing game for two players,” he said. “It must have taught the players strategic and tactical war skills, and helped develop them.”

They may have also been used for training, Saglamtimur added, to complement the nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles of our Early Bronze Age ancestors.

Finding the elephant

The region is no stranger to ancient board games. The Ancient Egyptian Senet, which means "passing", dates back some 5,000-years, just like the Basur pieces, and images of the game being played were represented on a number of tombs.

Today, one set is displayed in the Rosicrucian Museum in California, although there’s no clear information on when and where it was found.

'[The findings] in Anatolia some 90 years after and 800km north of the Ur discovery naturally created big excitement'

- Haluk Saglamtimur, Professor of Archaeology

The lavish Royal Game of Ur from Iraq, today on display at the British Museum, is another find.

Also known as the “Twenty Squares”, it was discovered by British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley, who led excavation teams at the Royal Cemetery of Ur in Iraq’s southern Dhi Qar governorate by the Euphrates River, from 1922 to 1934.

“Finding [the tombs and the gaming pieces] in Anatolia some 90 years after and 800km north of the Ur discovery naturally created big excitement,” Saglamtimur said.

Basur Mound’s overall connections with other regional ancient sites have also struck historians.

“[The Basur discovery] opens new perspectives for the understanding of the diversified political and cultural developments manifested in the societies of the Upper Tigris and Upper Euphrates regions," says Dr Marcella Frangipane, a professor of archaeology at Rome’s La Sapienza University, "ascribing a very active, albeit varied, role to the people of the Anatolian mountains in all the post-Uruk processes of changes.”

Saglamtimur agrees: “The discoveries helped fill in the gaps. With these excavations, we started to understand the timeline for civilisations that resided by the Tigris River, after years of works around the Euphrates Basin.”

The Tigris and the Euphrates rivers make the building blocks of the northern Fertile Crescent, also known as Mesopotamia, a historic region covering southeast Turkey, Iraq, Kuwait and northern Syria today.

Basur Mound is thought to have been an administrative centre in the late Uruk Period (3,100BC), based on the discovery of large stone structures and cylinder seals, and had been inhabited since 10,000BC.

Cuneyt Celikbas, 28, from the village of Aktas, is one of two sons of a Kurdish family who own the site on Basur Mound, some 20km northwest of central Siirt, near the Botan Valley.

He and his older brother Cemalettin both worked in the excavations on and off for over a decade and continued to look after the site once the project ended.

Nowadays, the huge open graves are concealed beneath overgrown grass, practically isolated as the water from the controversial Ilisu Dam project started seeping through since it opened on 19 May.

In February, the brothers had given one of the final tours of the site.

“There,” Cuneyt said, pointing to where one of the larger tombs was discovered. “I was here when the last elephant was found. We were very excited. Everyone applauded.”

“They were great days,” he said, recalling their work maintaining the site for the past 13 years. “I wish we could continue; there’s still much to be found here.”

‘One of the past decade’s most important archaeological discoveries’

Further discoveries are unlikely now, since many ancient sites in the Basur region are becoming submerged with the expansion of the dam.

“The Ilisu Dam, like all other dams on the near eastern great rivers, have certainly upset the landscape and left valuable sites under the water, heavily damaging the cultural heritage of countries rich in monuments and extraordinary archaeological sites,” Professor Frangipane said.

In February, US-based ARTnews dubbed this little-known excavation site “one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the past decade”. The site was praised for its contributions to our knowledge about society, as Basur offered a new perspective on class and culture.

“Burying wealth in the form of metal objects is considered a common trait of ancient civilisations, but in western Asia the tombs of Basur [Mound] represent the earliest example of this practice,” Lorenzo d’Alfonso, associate professor of western Asian archaeology and history at New York University said.

“The study of the bones showed evidence for human sacrifice in these tombs. Their discovery shows the first example, and possibly the provenance, of a different concept of wealth and value associated with a new warlord society,” he added.

The excavations might be over, but they are being followed up with a four-year research project at University College London and the Natural History Museum.

“Because of the political instability around Mesopotamia, archaeological information in the region has been muted for the past 30-40 years,” Saglamtimur said. “So, these excavations are followed globally.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].