UK government says payouts for Iraq abuse claims 'too many to count'

The UK government has received so many complaints from Iraqis who were unlawfully detained and allegedly mistreated by British troops that its defence ministry says it is unable to say how many millions of pounds have been paid to settle the claims.

Ministry of Defence (MoD) officials in London say they can provide approximate figures for the thousands of Iraqis who have lodged complaints against British forces involved in the 2003 US-led invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq.

However, they maintain that they cannot disclose how much UK taxpayers’ money has been spent settling their claims, saying that it would take weeks for civil servants to collate the figure.

The department is claiming that it is unable to disclose the sums paid at a time when the UK parliament is about to debate a deeply controversial law which would introduce a partial amnesty for the country’s service personnel who have committed serious crimes - including murder and torture - while serving outside the country.

Known as the Overseas Operation Bill, the proposed new law has alarmed human rights groups, the UK government's political opponents and many ex-soldiers, who fear that it will effectively sanction war crimes by British forces.

This week the opposition Labour party came out against the bill, arguing that it would undermine the country's commitment to a rules-based international order.

'Decriminalisation of torture'

Even the country’s most senior retired soldier, 81-year-old Field Marshal Charles Guthrie, wrote to the Sunday Times newspaper to warn that the proposed new law would provide room for “de facto decriminalisation of torture”.

Guthrie added that the measures “appear to have been dreamt up by those who have seen too little of the world to understand why the rules of war matter”.

The MoD’s current stance - refusing to disclose how many tens of millions of pounds have been paid to Iraqi nationals - is a reversal of its previous position: in June 2017, long before the Overseas Operations Bill had been conceived, the department was willing to give detailed figures for the amount of claims it had received and the payments made by that time.

In response to a request made under the UK’s Freedom of Information (FoI) Act, the department disclosed that it had paid £19.8m ($26m) in 326 cases brought before the UK courts.

In a further 1,145 cases, £2.1m ($2.8m) had been paid out by British military officers in Iraq between 2003 and 2009.

The payments included £2.8m ($3.7m) that was handed over in one of the few cases widely reported upon in the UK.

In September 2003, British soldiers detained Baha Mousa, a Basra hotel receptionist, and tortured him to death. Part of the episode was filmed by a soldier.

Having previously given Mousa’s family $3,000 in compensation, the British government was forced to make the multi-million pound payment after human rights lawyers in the UK asked the courts to compel it to hold a public inquiry.

The recipients included Mousa’s family and eight other men who were detained and tortured at the same time.

Thousands of payments

Since 2017, however, the number of payments to Iraqi former detainees has rocketed, according to the approximate figures provided to Middle East Eye following an FoI request.

The MoD says that payments have been made in around 1,200 cases brought in the UK. It added that a further 3,200 claims had been made in Iraq, although MEE has established that the true figure is higher.

But the MoD says it cannot disclose the amount of money that was paid in these 4,400-plus cases, claiming in response to an FoI request that it no longer has any self-contained file on the matter, and that it would take many hundreds of hours to scour its records.

MEE is appealing against the MoD’s refusal to release the figures.

Why was the British Army in Iraq and Afghanistan?

+ Show - HideThe UK sent forces to Afghanistan as part of the international coalition that invaded the country in 2001 following the 9/11 al-Qaeda attacks in the US, and to Iraq in 2003 as part of a US-led invasion to overthrow Saddam Hussein.

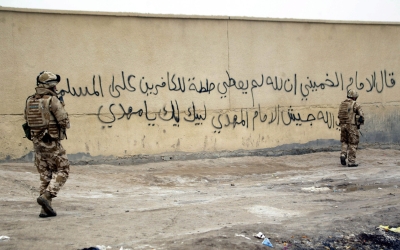

In both countries British soldiers became increasingly bogged down fighting against insurgents opposed to international occupation.

In Iraq, British forces were handed responsibility for security in Basra and three provinces in the south, but their presence was challenged by Muqtada al-Sadr’s Mahdi army militia fighters.

In September 2007, British forces withdrew from their bases in the city to the airport on the outskirts, the targets of “relentless attacks”, according to an International Crisis Group report which said that their retreat was viewed by locals as an “ignominious defeat”.

In Afghanistan, British forces had been deployed in 2006 to Helmand Province. But they proved ineffective against the resurgent Taliban and in 2009 more than 100 British soldiers were killed.

British troops eventually withdrew from Afghanistan in 2014, with 454 service personnel killed over the course of their 13-year campaign in the country.

Up until late 2016, the MoD was able to provide exhaustive figures on the payments that have been made to Iraqi nationals.

When the then-defence secretary, Michael Fallon, gave evidence to a UK parliamentary committee on defence in December that year, the MoD provided the committee with a statement that detailed almost 400 payments to individuals, of up to £425,000 ($559,000).

A few months earlier, a senior MoD official submitted a statement to a court in London in which he said that 3,326 claims had been settled within Iraq alone, with the largest number of payments being made in 2004.

The parliamentary defence committee was looking into the way in which some British soldiers had faced repeated investigation, year after year. It concluded that those inquiries should be wound up and the government must “not lose sight of its moral responsibility” to service personnel.

In one paragraph tucked away in the middle of its subsequent report, however, the committee acknowledged that Iraqi prisoners had been abused.

It said that this appeared to be in part because British military interrogators had received what it described as “inaccurate” training, which put them at risk of breaking the Geneva Conventions.

The report added that the MoD’s admission that training material for interrogations “contained information which could have placed service personnel outside of domestic or international law represents a failing of the highest order”.

MEE understand that up to 75 percent of the claims that Iraqi nationals have lodged against the British government have centred upon the conduct of British military interrogators.

Bitter dispute

Within days of the committee’s report being published, Fallon shut down the body that was conducting most of the investigations into the military abuses in Iraq.

After that, a bitter dispute opened up on the sidelines of British society, pitting defence ministers, some MPs and some military veterans’ groups against NGOs, human rights lawyers and many ex-soldiers.

At stake was control of the narrative of what had happened when British troops detained large numbers of men and boys in southeast Iraq in the years following the invasion.

Had the abuse of which many complained been a systemic matter - as the half-buried paragraph in the parliamentary report had conceded - or had their claims been orchestrated by “ambulance-chasing human rights lawyers”, as government ministers, MoD officials and even members of the committee maintained?

The Overseas Operations Bill was introduced into parliament in March this year just as the UK was about to enter its Covid-19 lockdown. It is due to be scrutinised by MPs after parliament returns from its summer break in September.

It proposes that there should be “a presumption against prosecution” of British service personal who commit crimes while serving overseas, except in “exceptional” circumstances, and providing five years have elapsed since the time of the offence.

Sexual offences are exempt from the proposed new law, while murder and torture are not.

Dominic Grieve, a former attorney general for England and Wales, has pointed out that this means a British soldier who rapes and murders a woman while serving outside the UK could be prosecuted for rape, but not murder.

While some politicians believe the proposed measures may be electorally popular in the UK, where support for its armed forces is traditionally robust, the bill’s critics say it is legally fraught, risks sending a dangerous message to young soldiers and is demeaning of the overwhelming majority of service personnel who have never committed a crime.

'Squalid' legislation

Some critics say they believe the proposed new law is rooted in a desire to prevent the prosecution of those military interrogators whose activities in Iraq have cost the UK taxpayer millions of pounds in out-of-court pay-outs, and whose prosecution could lead to uncomfortable questions for army commanders, senior MoD officials and government ministers being asked in court.

Frank Ledwidge, a former army intelligence officer and military historian, warns that the bill - which he calls a “squalid piece of legislation” - could cause more problems than it solves for the MoD and British government ministers.

Ledwidge, who has experience of tracking down war criminals in Bosnia and Kosovo, points out that the International Criminal Court (ICC), which is currently conducting a preliminary investigation into allegations of British war crimes in Iraq, is unlikely to target the interrogators.

“When the ICC does come for us, which it will if this bill is enacted, it won’t be the soldiers they’ll be after,” Ledwidge says. “The men we hunted down in Bosnia were not the trigger-pullers. They were the commanders, the generals and the politicians who sent them and allowed these crimes to happen.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].