In pictures: The unsung heroes of Syria's revolution

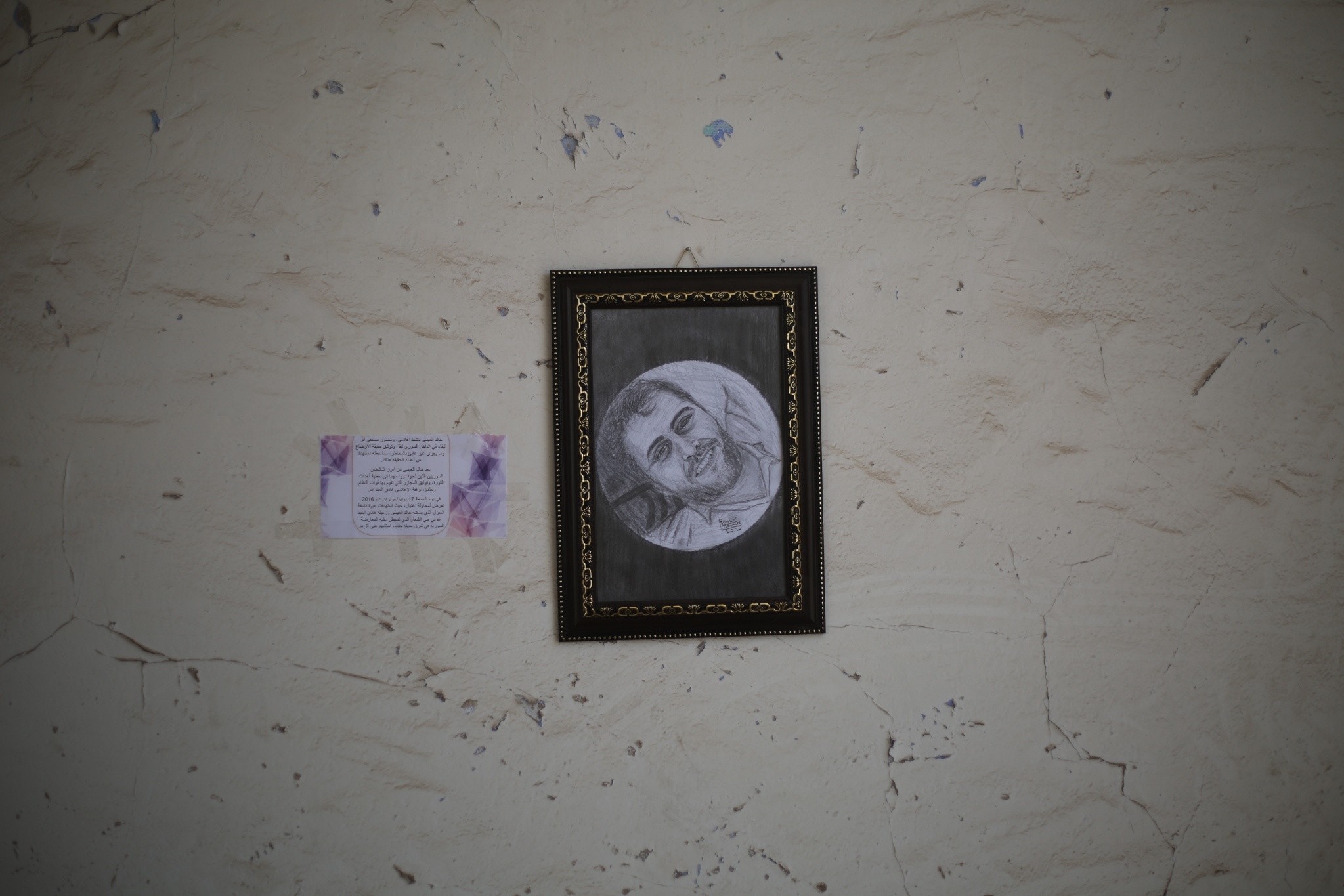

A series of artworks adorn the walls of a unique exhibition in the Syrian city of Idlib. Tacked up on the walls of a house destroyed by shelling during the country’s conflict, now in its ninth consecutive year, are portraits of revolutionaries, some of whom lost their lives in the ongoing war. (All photos by Ali Haj Suleiman)

Artist Rami Abd al-Haq, 29, launched the exhibition earlier this month, titled “Revolutionary Stands”. He says he set up the exhibit as an expression of gratitude and appreciation to these personalities who had "a great impact on our continuation in the Syrian revolution".

Damascus-born Basil Shehadeh was 28 when he was killed by a missile strike by government forces on his city of Homs in May 2012. Shehadeh had studied filmmaking at Syracuse University in the US before returning to Syria to document regime violence against demonstrators at the start of the country's revolution in 2011. He formed a team of reporters and taught them photography and video-editing, in order to show the world the reality in Homs.

One of those who attended Shehadeh’s funeral was Abdul Basit al-Sarout, a footballer renowned for his role in leading some of the earliest protests of the Syrian uprising in 2011 in Homs. He was dubbed the “singer of the revolution” and was known for popular revolutionary chants such as “This country rises with our souls rises, this country’s blood runs through our veins”. Sarout, who used to be a goalkeeper for the Al-Karamah football club in Homs, lost his four brothers and his father in the conflict. He then died from wounds sustained in a battle against government forces in June 2019 in the northern Hama province.

Suad al-Kiyari was a 39-year-old Free Army fighter from the town of Abu Dhahur in eastern Idlib. Known by the nom de guerre of Umm Aboud, Kyari joined the resistance initially as part of the Syrian Revolutionaries Front. She refused to leave her hometown, even as it came under attack from government forces and its allies, and was killed in an air strike on Abu Dhahur in January 2018.

Born in 1986, activist Ghiyath Matar called for peaceful resistance despite the violent suppression of protests. He became known for his offerings of roses and bottles of water to Syrian security forces during demonstrations in his hometown, the Damascus suburb of Daraya.

Following a suspected trap, Matar was arrested by security forces in September 2011, and his corpse later delivered to his family with signs of apparent torture. The ceremony mourning Matar’s death was attended by several ambassadors, including foreign diplomats from the United States, Britain, France, Japan and Germany.

Syrian writer and actor Adnan al-Zeraei was born in the Baba Amr district of Homs. After studying acting at the Higher Institute for Dramatic Arts, he wrote for the popular satirical television series Spotlight. Zeraei was forcibly disappeared after his initial arrest in Damascus by security forces in February 2012 led to his transfer to various detention centres, including the notorious Al-Khateeb security branch. He remains missing.

Khaled al-Essa from Kafr Nabl in Idlib province took to documenting his country’s uprising from 2011, filming protests in Idlib and Aleppo. Despite the risks, he and his colleague Hadi al-Abdullah insisted on remaining in Syria to cover the conflict. An explosive device was left near the pair’s home in eastern Aleppo on 16 June 2016, while they were covering the battles of Aleppo. They were both taken to Turkey for treatment following the blast and while Abdullah survived, Essa died from his injuries.

Raed al-Faris, a 46-year-old activist, became known for his protest banners in the early days of the Syrian uprising. He also formed several civil and media organisations, including Radio Fresh, which broadcast independent news. Faris was shot dead by masked gunmen in November 2018 in Kafr Nabl, along with his friend Hammoud Janeed.

One of those attending the exhibition, Obeida Dandoush, praised it for being “the first of its kind in Idlib”. Another attendee, Youssef Gharibi, said it was an opportunity to put faces to the names he had heard honoured in the past. “I’d never seen them. The exhibition was an opportunity to hear their stories and take photos to keep as souvenirs,” Gharibi said. “I hope that there will be more exhibitions like this to serves as a reminder of our revolution.”

Rami Abd al-Haq, who curated the exhibition of his own artwork, says he would love to live abroad and that he was studying in Lebanon but decided to return to Syria at the start of the uprising. He says he will not leave Syria until he sees the downfall of the current regime and “peace reigning”.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011, hundreds of media workers have been killed by Syrian government forces, militant groups and other parties. Abd al-Haq says he also hopes to direct a second message, this time at members of the international community who stood against the Syrian revolution, especially the “Syrian regime agents and allies who raised the slogan ‘Assad or we burn the country’”. His message, he says, is that “we will continue despite your attempts to destroy us".

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].