The Egyptian sculptor who made the Sphinx smile

The artist Adam Henein, who died this spring, didn’t just draw on ancient Egyptian inspiration for his sculptures. He made the Sphinx smile - and perhaps even breathe.

Around 30 years ago, Henein joined what might be called the longest-running conservation project in history - as a sculptor on a critical phase of work restoring and replacing stonework on the Great Sphinx. He was decorated for his efforts by the Egyptian government.

“I told Adam Henein a story that made him laugh,” said Dr Zahi Hawass, celebrated Egyptian archaeologist and at the time director general of the Giza Pyramids. “I told him when I came to the Sphinx in 1987 and I found that it had lost part of its right shoulder, I felt that the Sphinx was crying.

"But we restored the Sphinx and I came to look again at the Sphinx and the Sphinx was smiling.”

Adam Henein was born in 1929 to a family of metalworkers in Cairo. At the age of about eight, in a story he repeated often in articles and interviews, he went on a primary school trip to the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities. Deeply affected by the ancient Pharaonic sculptures, he made a clay figure of Pharaoh Ramesses II, which he presented to his father, a silversmith.

On his death this May, aged 91, Henein was mourned as one of Egypt’s most praised and popular artists, known for his paintings on papyrus, using natural pigments and Arabic gum, but above all for sculptures of bronze or granite. He represented the country in the Venice Biennale and exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The influence of Pharaonic sculpture on his work is felt constantly, in the calm clear lines of abstract boats or birds.

“Most of his work is influenced by ancient Egyptian art, in a very subtle way suited to Adam. You will find it in details, compositions, volume,” said Karim Francis, his former art dealer, who worked with Henein for 20 years.

The streamlined stillness of Henein’s abstracts of birds seem reminiscent of ancient Egyptian hawks, or a watchful dog, perhaps a play upon the big-eared God Anubis. A cockerel is almost hieroglyphic.

Henein was born in Cairo in 1929, and graduated as a sculptor from the Academy of Fine Art in Cairo in 1953. Visiting Paris in 1971 to join an exhibition of Egyptian contemporary art, he settled in the city for nearly 25 years.

He may have missed Egyptian aesthetics in Paris, said Rose Issa, a leading curator and writer on Middle Eastern art, but at the same time “he saw how the art deco, the old cinemas, and most of early 20th century modernity was inspired by Egyptian or Pharaonic antiquities, the lines, pure, simple, modern…the art deco furniture, film sets, dance costumes, all of which started in Russia, Hollywood - the Pharaonic influence was everywhere.”

“The Sphinx, on which he worked and supervised the restoration for years, was very much part of his life, his spirit, his friend,” Issa added. “Your nature and roots come out more easily when you are outside your country. But he always kept his country close to his heart.”

Resconstructing the Sphinx

But when Henein was first offered the chance of working on the Sphinx, the greatest Pharaonic sculpture of them all, he turned it down.

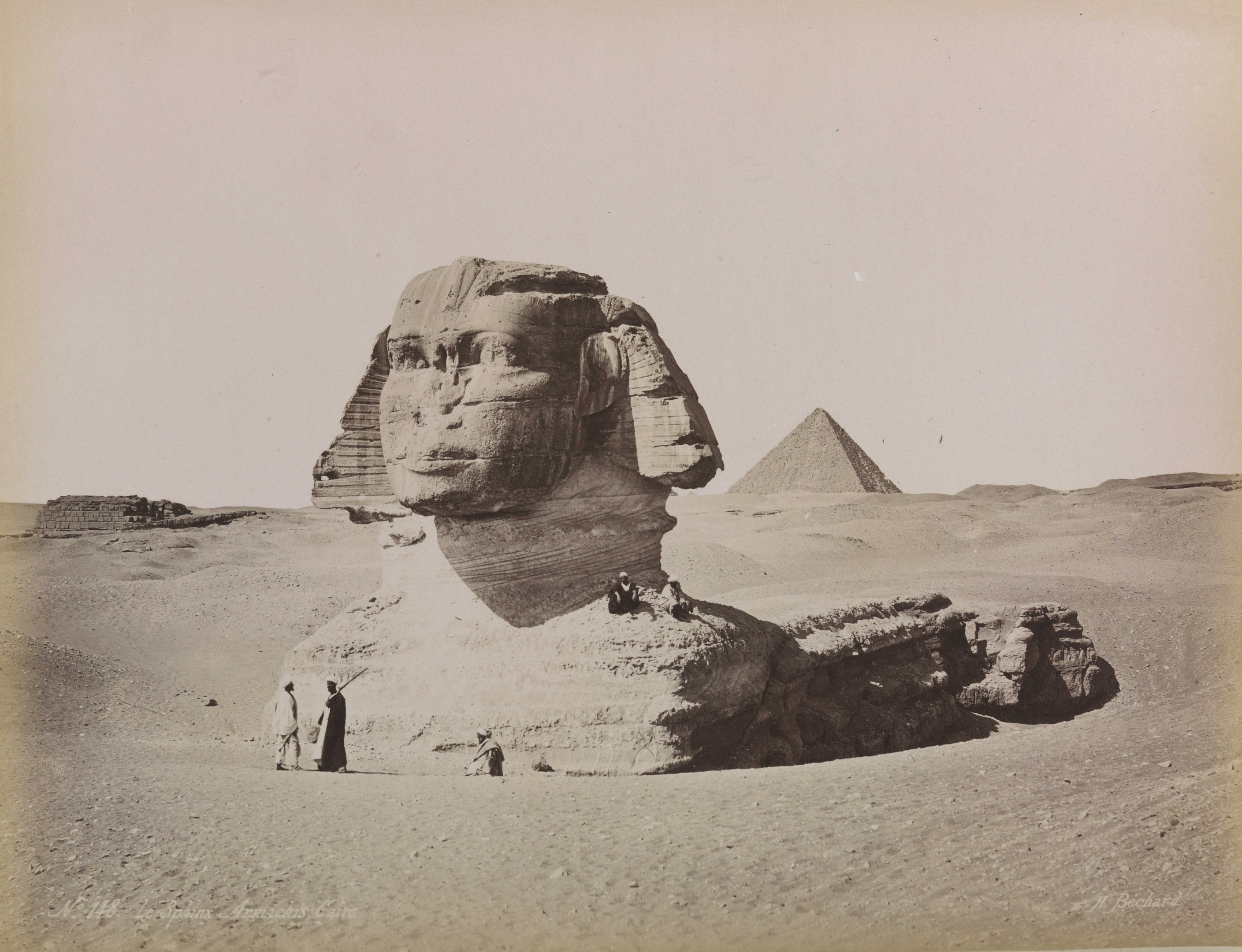

The limestone Great Sphinx is 66 feet high and 240 feet long, thought to have been carved under Pharaoh Khafre in about 2550 BC, or 4570 years ago. From early on the monument needed upkeep; erosion quickly took its toll, while more than once the Sphinx was dug out of drifting sand.

About 3,000 years ago, if not before, early and extensive repairs were made; sand was removed, a mud wall built for protection. It seems a beard was added, later falling off (the British Museum has a fragment, excavated in 1817). The Romans also repaired the Sphinx, while it’s thought the famous nose was damaged much later, sometime in the 15th Century.

There were several efforts at stabilising the Sphinx in the 20th century, from cement work in the 1920s to more extensive cement and cladding work in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1988, however, a large piece of stone fell off the Sphinx’s right shoulder, bringing fears about its condition and whether its entire right shoulder could collapse.

Then culture minister Farouk Hosny, also an artist, took an inspection tour with the archaeologist Dr Hawass and saw that “shameful” recent repair work, using modern cement next to ancient rocks, had created a much bigger issue than just the shoulder.

It was agreed a new round of restoration must involve a sculptor, and Hosny called on Henein, an old friend. The two men exhibited together several times, including at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hosny knew well how Henein was inspired by Pharaonic art, of his frequent visits to Egyptian museums.

At first Henein turned him down. “He initially said no, this is a very important piece, this is not something I can touch,” Hosny recalled.

“At this point I asked him to come and see and check the restoration work. When he went to the site he actually was horrified by how bad the restoration was, and he started to curse. At this point he agreed to take over, because he saw how badly it was done and he decided to save it.” Previous restorers, Henein later told Hosny, were “criminals” who ought to be prosecuted.

In 1989 Henein was named head of the design team, with a second sculptor, Mahmoud Mabrouk, and a team of stoneworkers. They worked from old photographs of the Sphinx, and a photogrammetric map. The team borrowed photographs from the US Library of Congress.

'A living statue'

The project included restoring not only the Sphinx’s arm and chest area but also the entire base of the monument, replacing mismatched stone and cement deep inside.

A quarry was located to supply matching stone, while ancient mortar at the site was analysed to produce a similar blend. Henein drew up the action plan over about 18 months, Hosny said. Proud of his contribution, he refused to be paid.

“Large stones had changed all the proportions of the Sphinx and they used cement that caused cancer to the limestone,” said Dr Hawass.

“So we began major work. The Sphinx did not need only an archaeologist as curator but needed a sculptor because we needed to return the proportions of the Sphinx to it.

“I told Adam that the Sphinx is not a stone, it is a living stone. That made Adam smile and he said ‘I really believed when I touch the Sphinx I am touching a living statue.’”

The Sphinx, Hawass said, “is the icon of Egypt. Anyone would leave his work completely, to be honoured to work on the Sphinx. I really feel Adam felt honoured to be invited to work with us.

“He did not carve the stones, he directed the workmen to know how to put the stones on the body of the Sphinx and keep the proportions of the Sphinx.”

Henein later continued his engagement with Egyptian sculpture when he became the founder - again with Hosny’s encouragement - of the International Sculpture Symposium in Aswan.

“He saw that Egyptian artists did not know any more how to use granite, the material that was used by the Pharaohs,” said the Saudi art expert Mona Khazindar, editor of a 2005 book on Henein and former director general of the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris.

'When he wanted an architect to build him a simple home, he paid for it with a sculpture of a donkey'

- Mona Khazindar, Saudi art expert

“They would do sculptures or 3-D work with wood, with stainless steel metal, but they did not know how to use granite. He wanted Egyptian sculptors to have the courage to use this material.”

Khazindar is among those who claim Henein as the most important modern Arab sculptor after his fellow Egyptian, Mahmoud Mokhtar, who died in 1934 and also drew on Pharaonic style.

But Henein was also a humble man, she said, who did not pursue commercial sales, but talked of the simple pleasure he took from watching the Nile and its boats. When he wanted an architect to build him a simple home, he paid for it with a sculpture of a donkey.

That attitude may explain why the British Museum only holds a small papyrus piece by Henein, an abstract form, whereas for the Iranian sculptor Parviz Tanavoli, for example, it has 23 works listed, from prints and silkscreens to two sculptures. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has one significant piece by Tanavoli and none by Henein.

L’Institut du Monde Arabe’s collection however includes Henein’s 1996 work Le Sage, a granite sculpture nearly two metres tall. The museum’s entry notes that Henein’s work is informed by his profound knowledge of Pharaonic statuary - including through his restoration of the Sphinx - developing a particular sense of volume and touch. It speaks of the sense of serenity and silent contemplation.

A second work is Paysage Gris (Grey landscape) a papyrus work resembling stoneware or granite but made with pointilliste grains of colour. The Barjeel Art Foundation in the UAE and the Dalloul Art Foundation in Beirut also hold Henein’s work.

Henein’s reputation will likely continue to rise. His home in the Harraneya district, not far from Giza, has been a museum since 2014, with a garden and three-storey building showing his sculptures and paintings. At least one new book on the artist is now in the works. Egypt’s Ministry of Culture are planning an exhibition in the lavish Aisha Fahmy Palace, on the banks of the Nile, a centre of Cairo’s art scene.

“Adam Henein is now the most prominent sculptor not just in Egypt but in the whole Arab region,” Hosny said of his friend.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].