Israel-UAE deal: Neither historic nor meaningful, it may never get off the ground

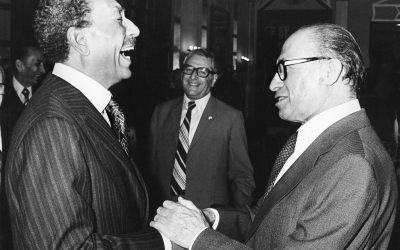

On 19 November 1977, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s plane landed in Tel Aviv as Israel held its collective breath.

Every Israeli old enough to have witnessed it on television remembers the moment when the plane door opened alongside the aircraft livery - “Arab Republic of Egypt” in Arabic and English - and Sadat began descending the steps towards the guard of honour awaiting him.

No one had to explain to Israelis that this was an historic moment. After four wars - 1948, 1956, 1967 and 1973 - during which thousands of Israelis and Egyptians were killed, the historic significance was self-evident.

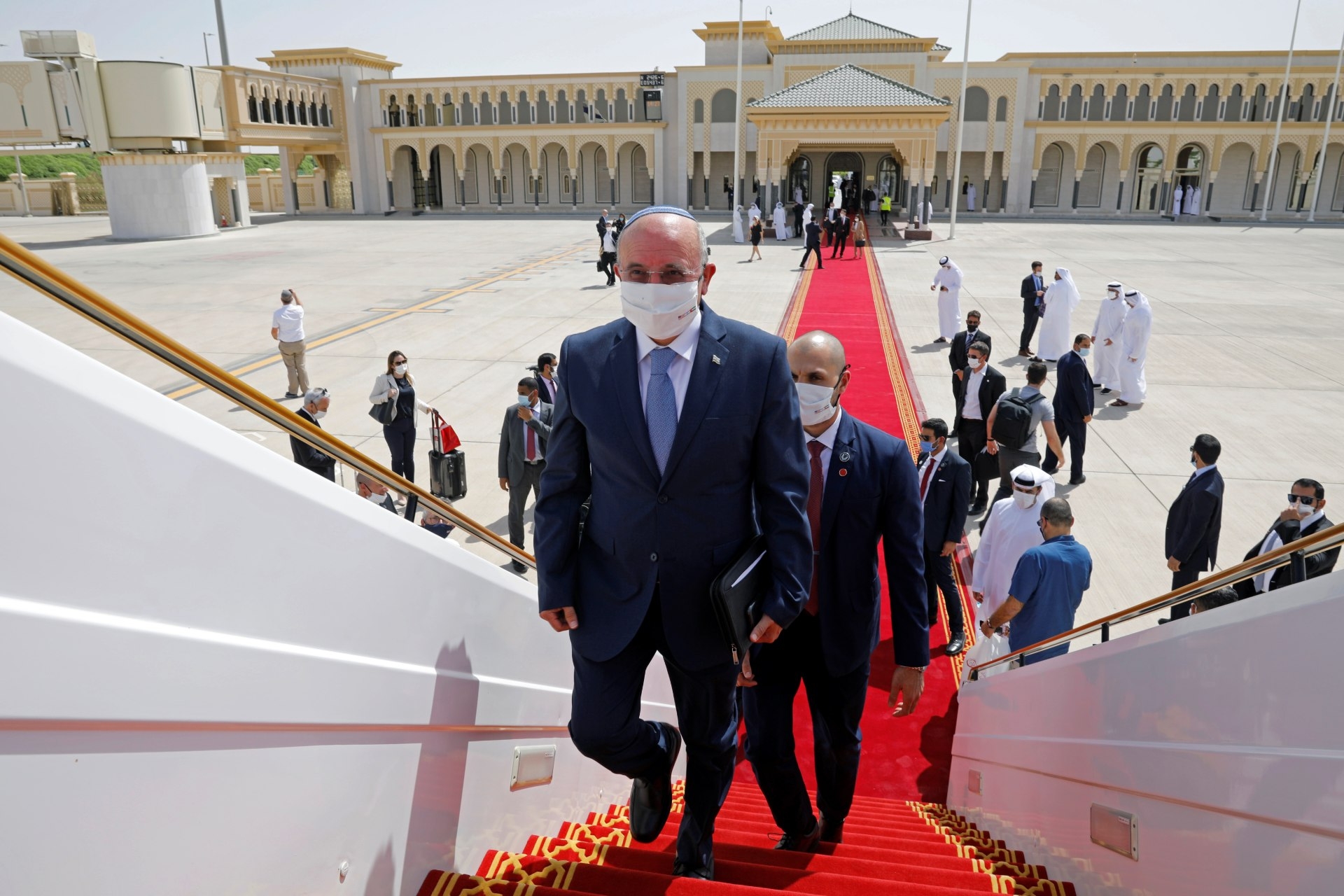

This week, on 31 August, the first-ever Israeli civilian flight to Abu Dhabi departed from Tel Aviv. The official Israeli delegation aboard was accompanied by an American delegation led by Jared Kushner, President Donald Trump’s son-in-law and adviser.

Yet the top headlines in Israeli media that morning were about the resignation of a senior finance ministry official amidst a coronavirus-driven leadership crisis over Israel’s economic policies.

Government figures, notably Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu himself, spoke of a “historic day” that would change the Middle East. The journalists on the flight attempted emotional impact, but Israeli television devoted only about three minutes to the event before pivoting back to what really interests the Israeli viewer right now: the start of the new school year in the shadow of Covid-19.

There are several possible reasons for this indifference on the part of most Israelis, first among them the coronavirus - thanks to which Israel is facing an acute economic and health crisis, among the worst it has ever known.

Having coped relatively well with the first wave of infection in March and April, the country is now counting around 2,000 new cases daily, placing it among the world’s leaders in the pace of infection. Unemployment in Israel is currently at 21 percent and rising compared with a rate of about five percent prior to the crisis. The safety net provided by the Israeli government to its citizens is among the most modest in the developed world.

Since the announcement of what is termed a “peace agreement” between Israel and the UAE, Israeli media has reported at length about the opulent hotels in Abu Dhabi and Dubai. Meanwhile, average Israelis are having trouble paying their bills.

Another reason is the simple fact that it is hard to sell the Israeli public on a peace deal with a country that has never been at war with Israel. Not only does the UAE share no border with Israel, the Emirates are also quite far away.

The flight from Tel Aviv to Abu Dhabi took three hours and 20 minutes, about the time it takes to fly from Tel Aviv to Rome. Flying from Tel Aviv to Baghdad, on the other hand, takes about an hour, and Iraq has shot missiles at Israel.

The trading relationship between Israel and the UAE was no secret, and Israelis have visited there openly. Hence the difficulty in persuading Israelis that this “peace” will in any measure reduce an ongoing threat to Israelis. The UAE was not perceived as a threat prior to the announcement of the agreement, and they are not perceived as such now, either.

Netanyahu and the Palestinians

And another thing. This one concerns Netanyahu.

It is true that he has now been in office more than 11 consecutive years, but politically his position is very precarious. He has failed to achieve a majority in any of the last three elections and was forced to cede veto power to the rival Blue and White party in the government he assembled.

He is also viewed as the principal figure responsible for the government’s inadequate handling of the coronavirus.

January 2021 is when the courtroom deliberations are scheduled to begin in his trial for corruption, and the last 10 weeks have featured repeated demands for his resignation amidst increasingly large street protests outside his Jerusalem residence.

Polls show that Netanyahu’s Likud party, together with other right-wing parties, may enjoy a majority if an election were held today, but faith in the prime minister himself is at its nadir. Nearly anything he does is perceived by large swathes of the Israeli public as just one more attempt to impede the judicial process against him.

Nearly anything Netanyahu does is perceived by large swathes of the Israeli public as just one more attempt to impede the judicial process against him

The “peace agreement” with a country Israel has never been at war against is viewed by many as part and parcel of his personal exertions to stay out of jail.

Netanyahu, of course, portrays things differently. In a press conference the other day, just after the Israeli delegation landed in Abu Dhabi, he quoted at length from A Place Among the Nations, a book he wrote himself.

Twenty-five years ago, he proclaimed to journalists, he wrote that Arabs would only come to the table to make peace when Israel becomes strong economically and militarily. Netanyahu stressed that he had been proven right that peace did not need to be secured by trading land.

It was cringeworthy to watch Netanyahu talking yet again about himself and only himself, even on a day he described as “historic for the people of Israel”. Yes, Netanyahu has talked up the idea of “peace for peace” ever since he was first elected prime minister in 1996, but even then this was not particularly innovative.

In 1923, Ze'ev Jabotinsky, spiritual father of Israeli rightists, authored an iconic article called The Iron Wall, positing similar views that were subsequently adopted by both the left and the right in Israel as the foundation for their political and security-related policies.

And when Prime Minister Menachem Begin agreed to return the Sinai Peninsula captured by Israel from Egypt in 1967, in exchange for a peace agreement with Sadat in 1979, he made sure that the peace agreement would circumvent the Palestinians. It enabled Israel to retain full control west of the Jordan River in historic Palestine, and expand the settlement enterprise that had accelerated after the Camp David accords with Egypt.

Begin went on believing that he would be able to finally dispense with the “Palestinian question” when he directed the invasion of Lebanon in 1982, culminating in the Palestine Liberation Organisation’s exit from Beirut. He even signed a peace agreement with Lebanon, which of course included nothing whatever regarding the Palestinian question and was quickly annulled by the Lebanese parliament amid civil war.

Prime Minister Ehud Barak was close to an agreement with Syrian President Hafez al-Assad early in 2000, with the declared aim on Barak’s part being to sideline the Palestinian question. Likewise, the accord signed by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin with Jordan’s King Hussein in 1994 mentioned not a single word about the Palestinians. And by the way, the peace accord with Jordan did not require Israel to return territories; it was a “peace for peace” deal. Thus even in this regard, the agreement with the UAE is not innovative.

Prior to its founding in 1948 and certainly in all the years since, Israel has always attempted to bury the Palestinian question. Netanyahu isn’t doing anything new on that score. But the policy hasn’t always worked.

Begin, after all, with his peace accord with Egypt in hand had every reason to think that Yasser Arafat and his cadres boarding ships in Beirut bound for Tunis would mark the end of Palestinian resistance. Five years later, the First Intifada broke out.

Moreover, Israel owes its escape from diplomatic isolation in the West, the developing world and even the Middle East to the only peace agreement it has signed thus far with the Palestinian national movement - the Oslo Accords of 1993.

Only after that did India and China finally open diplomatic relations with Israel, and only after Oslo did Israel begin conducting relations openly with the Arab countries of the Middle East - from openly visiting Morocco to sending representatives to Bahrain, the UAE and other countries of the region lacking official relations with Israel.

Netanyahu could not have arrived at an agreement with the UAE had not the Oslo accords first paved the way for Arab recognition, formal and nonformal, of Israel.

Israeli indifference

That may indeed be the deciding factor behind the widespread indifference among Israelis about this latest “historic” agreement with the UAE.

Perhaps the Jewish Israeli public is satisfied with the status quo of occupation and de facto annexation of the Palestinian territories. And if not precisely satisfied, Israelis are nevertheless unwilling to pay the price for a real peace agreement with the Palestinians, including the founding of a Palestinian state, withdrawal to the 1967 lines, and some resolution of the Palestinian refugee problem.

But neither are Israelis complete fools. They know that Israel’s real argument is with the Palestinians. Only the Palestinians can really bring peace, reconciliation and legitimacy for Israel. Not the UAE, nor Sudan, not Bahrain or even Saudi Arabia. Israelis realise that regularly scheduled flights from Tel Aviv to Abu Dhabi will not bring us any closer to a resolution of our conflict here.

One can understand the Palestinian fear that Israel’s agreement with the UAE will exacerbate their diplomatic isolation and impede Palestinians’ efforts to pressure Israel via boycotts, sanctions or other means. Yet one must admit, even prior to this agreement, the pressure on Israel was minor.

It will be very difficult for Netanyahu to sign an agreement explicitly requiring no annexation, since that would deal a powerful blow to his political base and present him once again as someone who makes promises without adequate backing

Despite Netanyahu's will, the deal with the UAE may bring back the Palestinian issue. While the peace accords with Egypt and Jordan did not explicitly address the Palestinian issue, the UAE may yet demand that their agreement include an Israeli undertaking not to annex territories in the occupied West Bank.

Another possibility is that the agreement might stipulate that such annexation would be considered a breach of the accord. That would constitute the first Israeli undertaking to limit its freedom of action vis-à-vis the Palestinians in an accord with an Arab country.

It would not be “land for peace”; it would be more like “non-annexation for peace”. But “peace for peace” it is not.

It will be very difficult for Netanyahu to sign an agreement explicitly requiring no annexation, since that would deal a powerful blow to his political base and present him once again as someone who makes promises without adequate backing.

Hence the agreement may ultimately not be signed, and Netanyahu and Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed may not be photographed together on the White House lawn, after all. In that case, what would linger on after all the brouhaha would be an upgrade in the economic and security-related relations between Israel and the UAE.

That, too, would be an achievement for Netanyahu, but certainly not something that will change the entire Middle East.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].