Fear and loathing in Gaza: Tales of a life under siege

I woke to the sounds of heavy bombardment. I heard my parents calling “Amal! Amal!” I got up and ran towards them. I tried to hold my mother’s hand but it slipped away. […] They said ‘Amal’s dead’. I screamed at the top of my voice: ‘I didn’t die! I’m here!’ I shook them but no one seemed to notice me. I saw them looking at my bed. I turned to find my burning corpse.

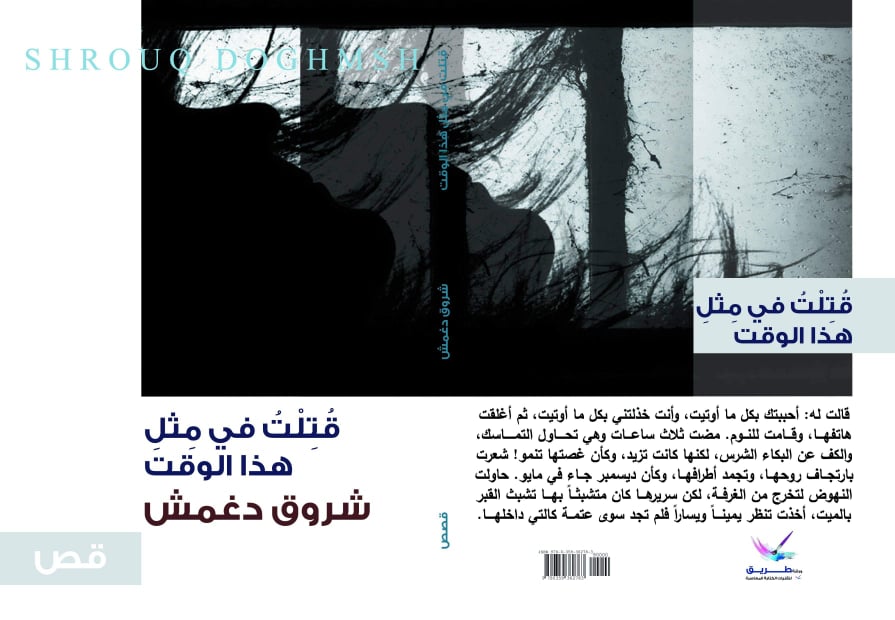

This excerpt from 21-year-old Palestinian writer Shurooq Doghmosh’s debut book of short stories is just one example of writing emerging from the Gaza Strip, which feature overriding themes of death and darkness.

The above excerpt from her story, I Found My Corpse, features a protagonist Dogmosh deliberately names Amal, which means “hope” in Arabic, because she would ultimately be killed off, along with any other semblance of optimism. Dogmosh’s collection, morbidly titled I Was Killed At Around This Time, is packed with stories that culminate in someone dying.

This murder, Doghmosh says, reflects her own vision of life in Gaza, which she experiences as filled with pain and loss. She herself is still mourning the loss of her uncle in the 2014 Israeli war on Gaza.

'Can you tell me about one day, just a single day, when you woke up in Gaza and didn’t feel powerless'

- Shurooq Doghmosh, Palestinian author

For these talented young writers, who grew up in a land under siege, it can be difficult to disengage from the harsh realities that inevitably seep into their writing.

"Life under siege destroys the soul. Sometimes I see this book as a way of mourning my soul that the siege destroyed, and robbed me of," Doghmosh says.

The Israeli-imposed blockade of 2007 has restricted movement of people and goods, leading to shortages - including electricity and power, economic insecurity and high levels of unemployment.

The constant threat of war and ongoing flare ups add to the climate of unrest for the nearly two million people living in the Strip.

The impact of growing up feeling so helpless is overwhelming, she says: “Can you tell me about one day, just a single day, when you woke up in Gaza and didn’t feel powerless, and as though everything around you has the potential to break you?”

‘Should I lie to my readers?’

“There is nothing in Gaza but pain and suffering,” Doghmosh tells MEE. “Yes, we smile sometimes and act like we’re OK, but we’re only pretending. The real, deep feelings we really have are darkness and fear. So how can I give people hope through my writing when I have lost it myself?

“Should I lie to the readers? If I don’t feel happy, I can’t fake it in my writing.”

That loss can come in many forms. 28-year-old poet Anees Ghanima’s debut collection, A Clown’s Funeral, won Al-Qattan Institution’s Young Writer Award in 2017. Ghanima was invited to the ceremony at the Palestinian Book Fair but after several failed attempts at sourcing a permit to leave Gaza, he couldn’t make it.

'We all live under the same conditions... the writer is able to express it, other just suffer in silence'

- Anees Ghanima, Palestinian poet

“Ramallah is another city in my country but I couldn’t get a permit to celebrate this success because between Gaza and Ramallah is an Israel checkpoint that doesn’t care about anything but breaking Palestinians and stripping them of hope,” Ghanima says.

Even when he writes about love, the words will gradually manoeuvre back to fear, and war. So much so that the judges described his book as presenting “a poetic force within a text derived from sadness and cruelty”.

In one poem, he writes: “I belong to all those wounded who lost their hearts in the war.”

“We were raised in a state of war,” Ghanima says. “Ever since we were born and until now, Palestinians are fighting occupation, and now also a siege. We never rest, and that’s the environment we grew up in.

“Whether we are writers or not, we all live under the same conditions. Whereas the writer is able to express it, others just suffer in silence.”

A little optimism does find its way into his writing, however, such as in the poem A Balcony That Doesn’t Overlook War, where Ghanima expresses his dreams for an end to war:

Tomorrow I’ll take a rest on a balcony

that doesn’t look out at war

I’ll smoke the cigarette I’ve always dreamed of

and from the palm of my hand,

sorrowful music will forever flow

But like hope, optimism is also fleeting.

“A person stuck in the darkness can’t talk about the light,” he says. “They have to see the light first so they can write about it and siege blocks this light.”

Art imitating life

The Palestinian struggle has, for nearly a century, been expressed through its literature, writes Palestinian Culture Minister Atef Abu Saif, in his introduction to the short story anthology, The Book of Gaza: “It has been the faithful scribe of their history, events, and tragedies, of the details of their displacement and refugeedom.”

“From the poems of Mahmoud Darwish, Samih al-Qasim and Muin Bseiso to the stories of Ghassan Kanafani, Emile Habibi and Samira Azzam, Palestinians have also made great contributions to Arabic literature more broadly,” Abu Seif writes.

Palestinian writing has evolved with the conflict, he explains. The short story, for example, gained popularity in the 60s onwards, even after Israel’s occupation of Gaza in 1967 when many of the writers took refuge outside the Strip.

Young writers 'grew more attached to their inner worlds as a way of speaking about the world at large'

- Atef Abu Seif, Palestinian Culture Minister

Writers in Gaza had to find ways to “overcome printing and publishing restrictions imposed by Israeli occupation forces,” and the “brevity and symbolism” of the short story were useful for this.

The content too of short stories coming out of Gaza grew from one focusing on “national issues and values” and “embodiments of grand ideas” to stories that “spoke more passionately about human failings” and the writers’ own pains and dreams. Young writers “grew more attached to their inner worlds as a way of speaking about the world at large”.

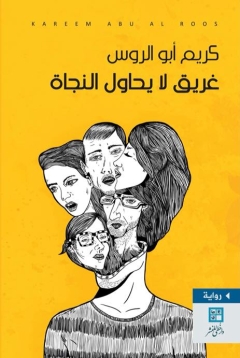

One such writer is 23-year-old Kareem Abu Al-Roos. Published in 2018, his debut novel, A Drowning Man Doesn’t Try to Survive, tells the frustrating tale of his protagonist’s lost love.

When the 22-year-old Jameel meets Linda in an art gallery one day they fall in love and dream of starting a family together. But the pair don’t have jobs, like many of Gaza’s youth, and little by little the challenges against their idyllic imagined future mount up.

Linda eventually decides to leave Gaza to find better opportunities elsewhere, leaving a broken Jameel behind.

With the unemployment rate in Gaza having reached 46 percent this year, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), and with around 70 per cent of the population under 30, Palestinian youth especially feel the brunt of the siege.

Gaza’s annual average income is less than $2,000, suggesting that an average wage is hardly enough to start a family, let alone sustain a literary career.

“The restrictive siege, which doesn’t help people find dignified jobs, means artists and writers in Gaza fail to secure a job, or a livelihood,” says Abdullah Tayeh of the Palestinian Writer’s Union.

Getting published itself is a feat since, as Tayeh points out, “writers have to pay the costs of printing their own work out of their own pocket.”

Through Jameel’s story, Abu al-Roos recounts his own feelings:

I forgot everything and remembered that I am still a prisoner, a prisoner in a roofless prison, that forces you to feel the darkness, and at the same time powerless.

Yet it’s in the act of writing that Abu al-Roos finds some solace: “We liberate ourselves from the siege by writing about it and express our pain to the world to let them know what our life in Gaza is like.”

But this is not a solution, says Tayeh: “Even though the current situation does not help artists and writers to find the space to be optimistic, writers shouldn’t let their work become depressing and pessimistic.

“If they sink into depression and pessimism, then it is like someone who kills themselves, and their cause, with their own hands.”

Healing through hope

But not all the works coming out of the Strip reflect a morbid outlook on life.

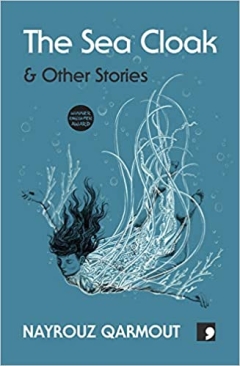

Born in the Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus, writer Nayrouz Qarmout returned to Gaza aged 11 following the 1994 Israeli-Palestinian Peace Agreement, where she has lived ever since.

While it’s true that Palestinians have grown up in uniquely debilitating circumstances ever since the Nakba of 1948, Qarmout, 36, says it is possible to express cruelty and sadness, without falling into those feelings yourself.

“I tend to prefer writing that is more balanced, that is capable of depicting how a person is when they are sad and when they are happy,” says Qarmout, an author, journalist and women’s rights campaigner.

“Life can’t be free of sadness, and this can be reflected through art. And life can’t be free from happiness... How can you know if you are sad if you have never been happy?”

The 11 stories in her debut collection, The Sea Cloak, draw on her experiences growing up in a refugee camp and reveal the daily struggles of Palestinians in Gaza. She writes about characters young and old, women, refugees, and orphans dealing with the aftermath of bombardment.

In the first story, The Sea Cloak, a young woman wades into the water dressed in her long black cloak and headscarf, yearning for the sea and an escape from the “noise of the past”:

She sunk her toes into the wet sand, her footprints as light as a butterfly’s dissolving instantly away. She moved forward, fearful of what was to come. Her foot had plunged into an abyss too deep to escape. But she continued, happy to have fallen.

In 2018, the book, which was translated into English by Perween Richards, was nominated for Edinburgh International Book Festival’s First Book Award.

She too faced travel hurdles, initially when her permit applications at the Erez crossing were stalled and then when her visa was repeatedly rejected by the UK Home Office, and a hashtag #sorrynayrouz was launched to spotlight her troubles.

But, unlike Ghanima, Qarmout was able to eventually make it to Scotland to celebrate her nomination, with festival organisers arranging to host her in a special event since she had missed the one she'd been scheduled for.

“When I went to the UK I saw just how developed it was and how we are so isolated in Gaza from the rest of the world, without any capability for development,” she says. “Imagine that in 2020, Palestinians in Gaza have never seen the kinds of trains I saw there.”

Qarmout says that Palestinians have been living a much older siege than the one imposed by Israel in 2007: “Ever since the Nakba, have we lived in a normal way? No. We were living under a military curfew in the 2000 Intifada and were not able to move. That was as brutal as the current siege is.”

At one point the protagonist from her sea cloak story finds herself dragged down by the water, and her heavy cloak. She is close to drowning, before she is finally rescued by a young man who pulls her out to the safety of the shore.

But for a moment, even as the sea is becoming a threat, the young woman murmurs to herself: “I want to keep swimming”, cherishing this feeling of “boundless joy”:

The sea’s symphony, familiar and divine, caressed her ears. Her heart slowed and reached out to the desolate expanse of water. She opened her eyes and was dazzled by golden ripples stretching out as far as she could see. Her body sunk into their warm embrace.

“I don’t allow the siege to enter my imagination,” Qarmout says. “And this is the difficult challenge that the writer lives in light of this life under siege which leaves its mark on everyone.

“An artist knows that no matter how dark the road, at the end there is a glimmer of hope, no matter how depressing the circumstances are now.”

Shurooq Doghmosh's novel, I Was Killed at a Time Like This, is published by Tareeq Publications; Anees Ghanima’s poetry collection, A Clown’s Funeral, is published by Al Ahlia Press; Kareem Abu Al-Roos's novel A Drowning Man Doesn’t Try to Survive, is published by Khota Publications, and Nayrouz Qarmout's collection of short stories, The Sea Cloak, is available from Comma Press, translated by Perween Richards.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].