'In a day, a city can be destroyed': Kuwait artists remember the Iraq invasion

Art has often been used as a way to reject war and expose its brutality. Picasso, Dali, Goya, Rubens and Bruegel all responded to global conflicts by creating art.

The large-scale paintings of American-Lebanese artist Nabil Kanso often depict apocalyptic scenes stirred by the Vietnam war or the Lebanese civil conflict, while renowned Iraqi sculptor and painter Dia Azzawi portrays the destruction suffered by his country, but also the plight of the Palestinians and Kurds.

For artists in Kuwait, one crisis that had a lasting impact on their life and work was the 1990 Iraqi invasion and subsequent Gulf War, that saw hundreds of Kuwaitis killed or tortured and hundreds of oil wells torched.

On 2 August 1990, Saddam Hussein had ordered his troops to invade Kuwait in a bid to claim it as Iraq's 19th province, a move triggered by land and oil disputes, along with heavy debts incurred by the eight-year war against Iran that ended in 1988. Following the US-led coalition war against invading Iraqi forces, dubbed Operation Desert Storm, Kuwait was liberated on 28 February 1991.

To mark this year’s 30th anniversary of the invasion, Kuwaiti cultural institution Al Shaheed Park created Confluence, a sculpture and a virtual memorial for Kuwait’s “martyrs and heroes of the Iraqi invasion”.

Conceptualised by Kuwaiti architect and artist Jassim al-Nashmi, who was born during the last months of the war, the virtual installation invited locals and worldwide participants to create a socially interactive installation on its website using digital and geometric “building blocks” that, when connected, formed a sequence of pointed arches.

The choice of ten coloured blocks symbolised “human virtues'' attributed to the victims: unity, perseverance, faith, loyalty, patriotism, alliance, patience, survival, bravery and resilience.

“All I did was set up the platform and allowed people to build the memorial they wanted to see in 3D, and there were over 2.000 contributions,” al-Nashmi tells MEE.

Along with the virtual installation, al-Nashmi also created a physical sculpture at the Al Shaheed cultural park, which was on view until 2 September. The name, Confluence, given to both structures, is in reference to the unity between Kuwaitis and allied forces during the liberation of the country, al-Nashmi says.

“The idea came from the expression 'one hand doesn't clap alone' and how a group of individuals can create strength in numbers. They can create an arch from the confluence - and the arch represents strength,” al-Nashmi explains.

The Deep Wound

Over the years, a number of artists in Kuwait have used their work to reflect on the consequences of the Iraqi occupation and the impact of the war. Human suffering and prophecies of war have always been present in the work of pioneer and prolific artist Khalifa al-Qattan (1934-2003).

The first Kuwaiti to hold a personal exhibition and the founder of Kuwait’s homegrown art movement that he named Circlism - an art form relying on circular and curved lines based on philosophy, spirituality, and science - Qattan found himself unable to paint during the war for fear of repercussions. A number of his paintings are on display in the family’s own museum, the Khalifa & Lidia Qattan Art Museum in Kuwait, and are exhibited in collections around the world.

In the seven months of occupation, the then 56-year-old artist “was glued to the radio, he listened and recorded all kinds of news,” Lidia al-Qattan, his Italian-born wife, writer, and artist recalls.

“He would also spend a lot of time working his archive or in the garden with his plants and growing vegetables. He could not paint because if the Iraqis came - as they sometimes did by barging into Kuwaiti houses by surprise - and they found any document, picture, or anything pertaining to Kuwait, they would kill you.”

As a person prone to depression, Lidia explains that during the occupation her husband was surprisingly optimistic and hopeful. “We knew that there was positive news coming with the coalition, that they were going to liberate Kuwait, it was just a matter of time.”

But Qattan had already painted plenty of war: by the time Iraqi tanks rolled into Kuwait, he had amassed a collection of 47 oil paintings on the theme of conflict, dating back to the 60s – from reactions to the Hiroshima bomb, Vietnam, to the ongoing suffering of the Palestinian people.

Since they are mostly symbolic works open to different interpretations, they are also considered prophetic of conflicts to come. One of his most famous is The Deep Wound (1984), a self-portrait of the artist, standing behind bars with a desolate gaze, an open stabbing wound on his chest. Six Arab men in miniature, dressed in traditional attire, stand in front of the painted Qattan.

Though the work was inspired by events that deeply affected the artist, his family reinterpret it today, seeing the Arab figures as representing the betrayal of Kuwait by some of its former Arab allies.

“The hand without skin might symbolise one of the methods of torture Iraqis used against the Kuwaiti resistance by

In the period following the end of the Gulf War, there was a marked shift in Qattan’s work, with more paintings devoted to some of the “tortures endured by the Kuwaiti men and women of the resistance,” his wife says.

In The Martyr’s Plant (1992) we see the tortured back and mutilated arm of a woman, while in The Document (1991) there is a tortured human torso with amputated limbs and head. Attached to the painting is a document purportedly authorising torture on suspected members of the Kuwaiti resistance.

“Some people when they see Qattan’s work might think it is grim - it has very dark but at the same time strong colours,” his daughter says.

“It’s because my father wanted to convey human suffering, corruption, the play of powers, greed, the illnesses of society in general.”

Who Killed the Deer

“Military, soldiers, guns and bombs were everywhere... The smell of death was everywhere”, pioneer Kuwaiti artist Thuraya al-Baqsami recalls of the seven months of the invasion.

The experience of occupation deeply influenced her creative process to a point that all she could paint until 1995 was war.

“Artists in any country and of any religion who went through war will not be the same artists they were before. Their art will be sad and full of anger,” she says.

According to Baqsami, before the Gulf War it was rare to see a Kuwaiti painting portraying human tragedy: “Many artists were busy with landscapes and beautiful things happening around them… But after the liberation for many years you could not find a painting of a vase, a flower, a door or a house. Everybody was trying to show what happened not only through art but also with literature, theatre and music.”

One of the Arab world’s most influential female artists and an author of widely translated novels, short stories, poetry, and essays, Baqsami’s work has been featured in over 60 personal exhibitions and hundreds of shows.

Her art is also part of permanent collections worldwide including at the British Museum, the Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi and Paris Unesco headquarters.

During the occupation she painted day and night and produced 85 works as part of her Invasion 1990-1991 series. “They [Iraqis] were bombing and I was painting. I used pastel, aquarelle, acrylic. I painted on stone, on wood, on paper, on anything I could find.”

Despite being scared, unlike Qattan, she painted voraciously during that period. In order to circumvent the Iraqi officers she used coded symbols, mostly inspired by various-shaped Dilmunian seals found on Failaka Island, an archaeological site off the coast of Kuwait city.

The scorpion attacking a man in The Witness (1990), for example, represents Iraqi soldiers, while the gazelle in Who Killed the Deer (1991) symbolises Kuwait. “Many times Iraqi soldiers stormed into my studio but they never understood my work.”

She would portray men and women like “mummies, bald and pale” with heads perforated by bullets like in The Last Shot (1991). “When the soldiers saw the paintings all they could ask was why all the figures were bald,” al-Baqsami says.

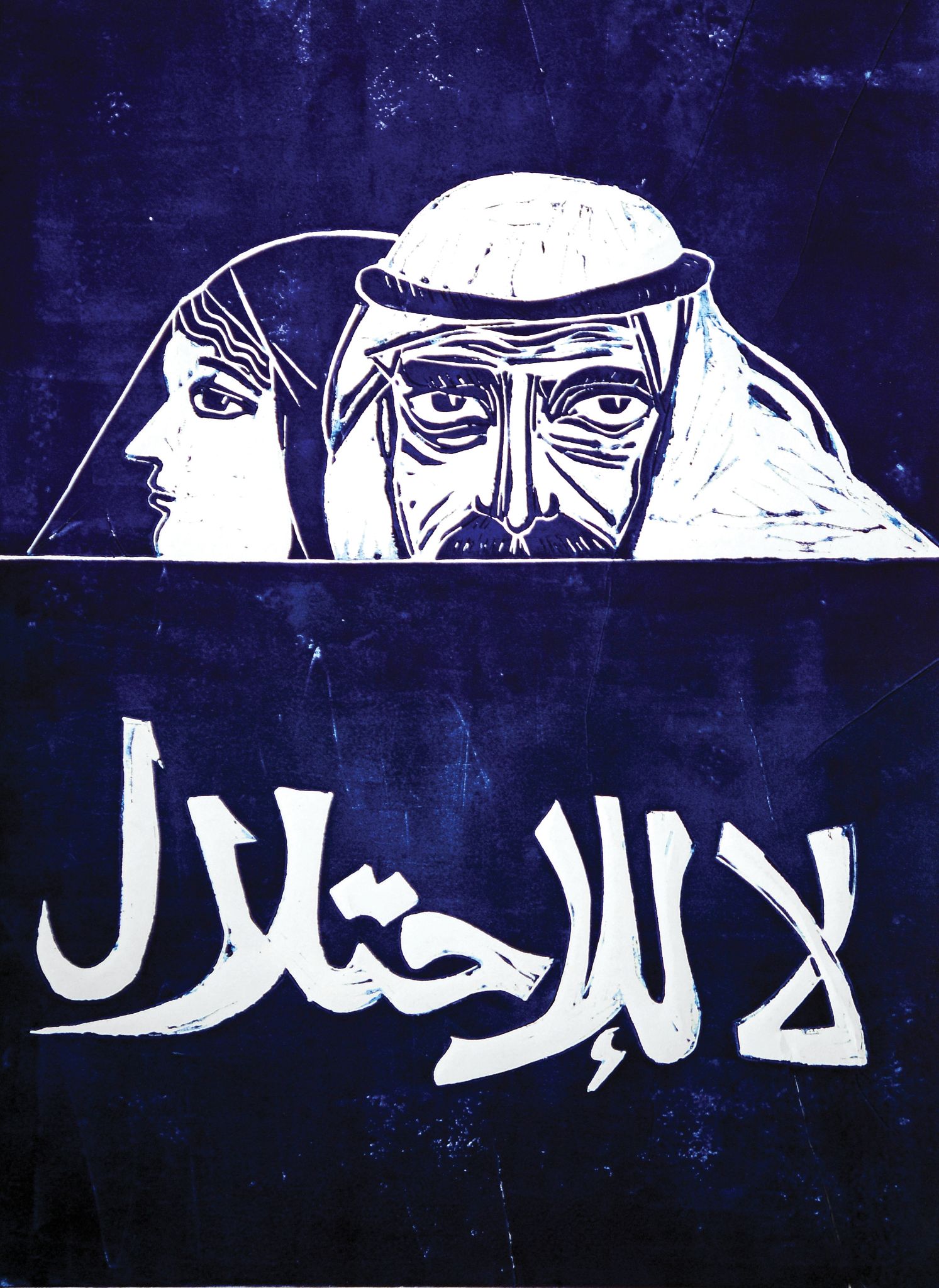

In the linocut print No to the Invasion (1990), one of her most famous works, a Kuwaiti man and woman in traditional attire oppose the occupation with a sentence written in Arabic calligraphy, reading: “No to the Occupation.”

Completed following the fourth day of the invasion, Baqsami printed copies of this piece and distributed it as a poster among members of the Kuwaiti resistance. When an activist was executed for distributing it, Baqsami stopped printing.

Three days before liberation, her husband was captured and held in Basra for almost two months as a prisoner of war. This is when she stopped painting.

“I was very scared. Suddenly I was alone with my three daughters while the rest of my family was out of Kuwait. I had nobody and did not know what would happen to me and my children,” she says.

“Thank God after three days Kuwait was free. I was happy but not complete until my husband was released at the end of March.”

'We learned a big lesson; we have to keep peace'

- Thuraya al-Baqsami, artist

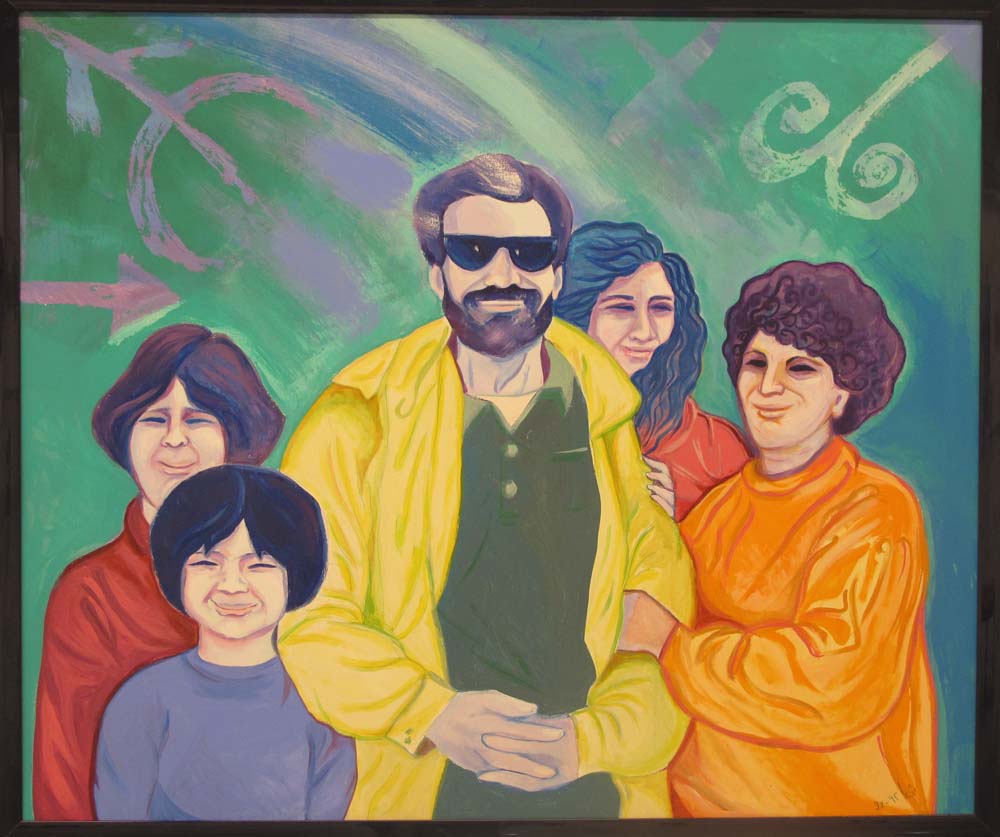

Baqsami captured the joy of the homecoming in the family portrait Return of the Parted (1992).

The horror of war is also rendered in three of her 12 books. Fatooma’s Diaries (1992) is a children’s book about war, while Cellar Candles (1993) is a collection of short stories that was awarded the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS) prize as the best literary work about the occupation.

Despite all the adversities, Baqsami never regretted having stayed in Kuwait: “I managed to watch, to feel everything. I was a witness of this big crime that happened in my country... To be occupied by another country is hard to forget but we learned a big lesson: we have to keep peace.”

Desperate measures

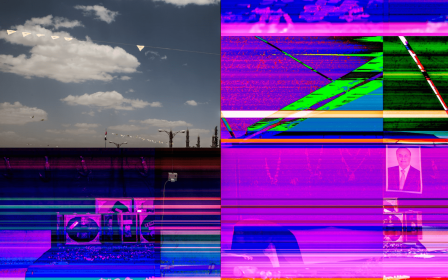

Aseel AlYaqoub's mixed-media installation Desperate Measures (2017) is inspired by an episode during the Gulf War when Kuwaitis saw Iraqi soldiers in gas masks, sparking rumours of a chemical attack. The Kuwaiti resistance then disseminated instructions for DIY gas masks through leaflets and word-of-mouth, prompting AlYaqoub’s mother and aunts to stich masks in their kitchen.

The first part of the installation is an eight minute video titled Semiotics of War in the Kitchen. In the performance, AlYaqoub sits in the same kitchen her family were in 30 years ago. Following her mother’s instructions, she attempts to recreate gas masks with coloured cotton fabrics filled with coal, that would have served to absorb poisonous gases. In the video we see how chaotic the process is and that the rudimental mask doesn't serve its real purpose and barely even covers the nose.

“We always slept in our clothes, in case we needed to quickly escape,” says AlYaqoub, whose memories of the occupation are vivid, despite being only four-years-old at the time.

In 1990, she was living in a large household based at her grandparents’ house. “The women were afraid of rape,” she says. “We moved to the basement when the actual war happened and slept on mattresses on the floor. I remember a mouse was spotted one day and none of us could really sleep that night. My cousin and I called it Saddam's Rat.”

Because the house was close to Dasman Palace (the residence of the Kuwaiti emir), the AlYaqoubs could witness the Battle of Dasman, when the Iraqi forces, on the first day of the invasion, took control of the palace in eight hours.

While the emir, Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmad al-Sabah, had relocated to Saudi Arabia before the assault, his younger brother, Fahd al-Ahmad, was killed defending the palace.

'[Kuwait] needs to undergo a psychological analysis to at least prevent history from repeating itself'

- Aseel AlYaqoub, artist

“We were on the balcony and saw the palace lighting up in flames, heard gunshots, and saw tanks. My mother turned on the TV and KTV [Kuwait's official state-run television station] was abruptly interrupted before our eyes. It was hijacked by Iraqi propaganda."

In addition to Kuwait, AlYaqoub’s work is featured in New York, London, and Budapest, and mostly focuses on Kuwait’s collective memory and its past. Like the rest of her work, the war became an experience that she explored from the Kuwaiti perspective.

As an artist, AlYaqoub believes in the importance of visually documenting accounts of war in the hope of unearthing any residual post-traumatic stress disorder.

“The history of the Gulf War has become diluted over time as Kuwait sought to build new diplomatic relationships with Iraq, which is understandable,” she says. “However, I do believe that the nation needs to undergo a psychological analysis to at least prevent history from repeating itself.”

No war orphan

On the first day of the invasion, illustrator Zahra Marwan was a two-year-old toddler at home with her mother. Her father had gone to work not knowing the country had been invaded, until his secretary called to tell him she wasn't coming.

Hours later her uncle, who was a soldier, was killed by a grenade while fighting on the frontlines.

In Grateful a Carton of Milk Didn't Turn Me into a War Orphan (2020), Marwan recalls with her signature watercolours and ink an episode that could have changed her life drastically.

While Marwan was home with her aunt one day during the early days of the occupation, her parents went out to buy some milk and were apprehended by Iraqi soldiers on their way back.

“They [soldiers] made them get out of the car and sit on the sidewalk awaiting a fate of becoming prisoners of war, or death,” she says.

The soldiers could have thought they were part of the Kuwaiti resistance if it weren’t for the carton of milk they held in their hands. The simple illustration depicts a bright blue and white oversized carton placed next to an image of Marwan’s parents, as if there to protect them.

Whenever she told people the story, she says, they were amazed at how their fate came down to a carton of milk. “Many of our family stories of the invasion felt similar. Impressions of humour among the horror.”

Marwan’s family remained in Kuwait until the end of the occupation, at her grandparent’s home with their extended family. The family eventually moved to New Mexico when she was seven but returned to Kuwait each year. After studying visual arts in France, she is now a full-time illustrator based in Albuquerque.

Inspired by modern picture book illustrators and by the flat imagery, elongated limbs and colours used by the Vienna Workshop artists, her nostalgic drawings focus mainly on family narrative and memory.

She also uses her skills to tackle the sensitive topic of the stateless minority, or bidoon, of Kuwait, drawing on first-hand experience. Despite her mother being a Kuwaiti citizen, Marwan was born stateless in Kuwait as her father was a bidoon and women cannot pass nationality to their children.

About a wedding portrait the artist made of her parents, she comments on social media: “Why didn't the country ever recognise my dad as Kuwaiti?”

Although Marwan has no memories of the war, she too carries the mark of the conflict.

“I grew up thinking that everyone's childhood started with war," she says. "I carry within me now in my thirties the constant uncertainty that in a day, a city can be destroyed.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].