Joe Biden, Emgage and the muzzling of Muslim America

What if he wins again?

As early voting gets underway in what has ceremoniously been dubbed the most important election in recent memory, liberal talk show hosts, mainstream newspaper columnists, and social media influencers are lamenting what a potential second term for Donald Trump would look like.

Since entering office in 2017, the reality TV star and businessman has ushered in an era of intense political polarisation, repeatedly promising to turn Muslim Americans' darkest fears into reality.

He has failed to denounce far-right extremist and racist groups and sentiments when prompted, signed an executive order banning people from six Muslim-majority countries from entering the US, and suggested that, under his administration, Muslims may be listed and recorded in a national database.

Should Trump win on 3 November, the next four years could be more disruptive to US foreign policy and world affairs than the last four.

For many Muslims then, the election offers only one stark choice: vote Joe Biden and stave off a Trump re-election.

But in recent months, a growing number of Muslims, who have a long-held distrust of the Democratic party, have expressed alarm that the election promises little more than a potential step back from Trump-inspired fascism.

'I remain unsurprised at the cadre of Muslim Americans eager to step up in defence of US empire-building'

- Nazia Kazi, Stockton University

For many, the election has opened a Pandora's box of uncomfortable questions, including: "Who gets to speak for, decide on, and represent the Muslim community's issues in the corridors of power?"

At the centre of that vexation is an organisation named Emgage.

Despite relative obscurity just a few years ago, Emgage, which describes itself as "the first and largest" national Muslim American political action committee (PAC), has enjoyed sizeable media coverage in the months and weeks leading up to this presidential election.

The publicity stunts began earlier this year, but much of the attention focused on Emgage stems from an online summit held this summer in which Biden addressed the Muslim American community.

An appearance by a presidential candidate at a Muslim event would have been unthinkable, Democratic insiders say, during Barack Obama's 2008 campaign, with the former president routinely fending off rumours that he was a Muslim for a large part of his candidacy and presidency.

But Trump's frequent attacks on Islam and Muslims have created what the Biden campaign sees as an opportunity to snap up a chunk of the electorate in several swing states, including in Michigan, Ohio, Florida and North Carolina.

There are an estimated 3.45 million Muslims in the United States - a tiny portion of the population - but the Muslim vote in Florida for George W Bush, for instance, is sometimes credited with making Bush president in 2000.

While Emgage has received attention from the Biden campaign, very little is publicly known about the organisation's actual ties to and place in the Muslim community.

But Muslim American community organisers who have long known the group, its founders and board members - and its links to pro-Israel groups - say Emgage's rise to national prominence is not the story of a group that advocates for the Muslim community, but rather one that is meant to muzzle it.

The story of Emgage

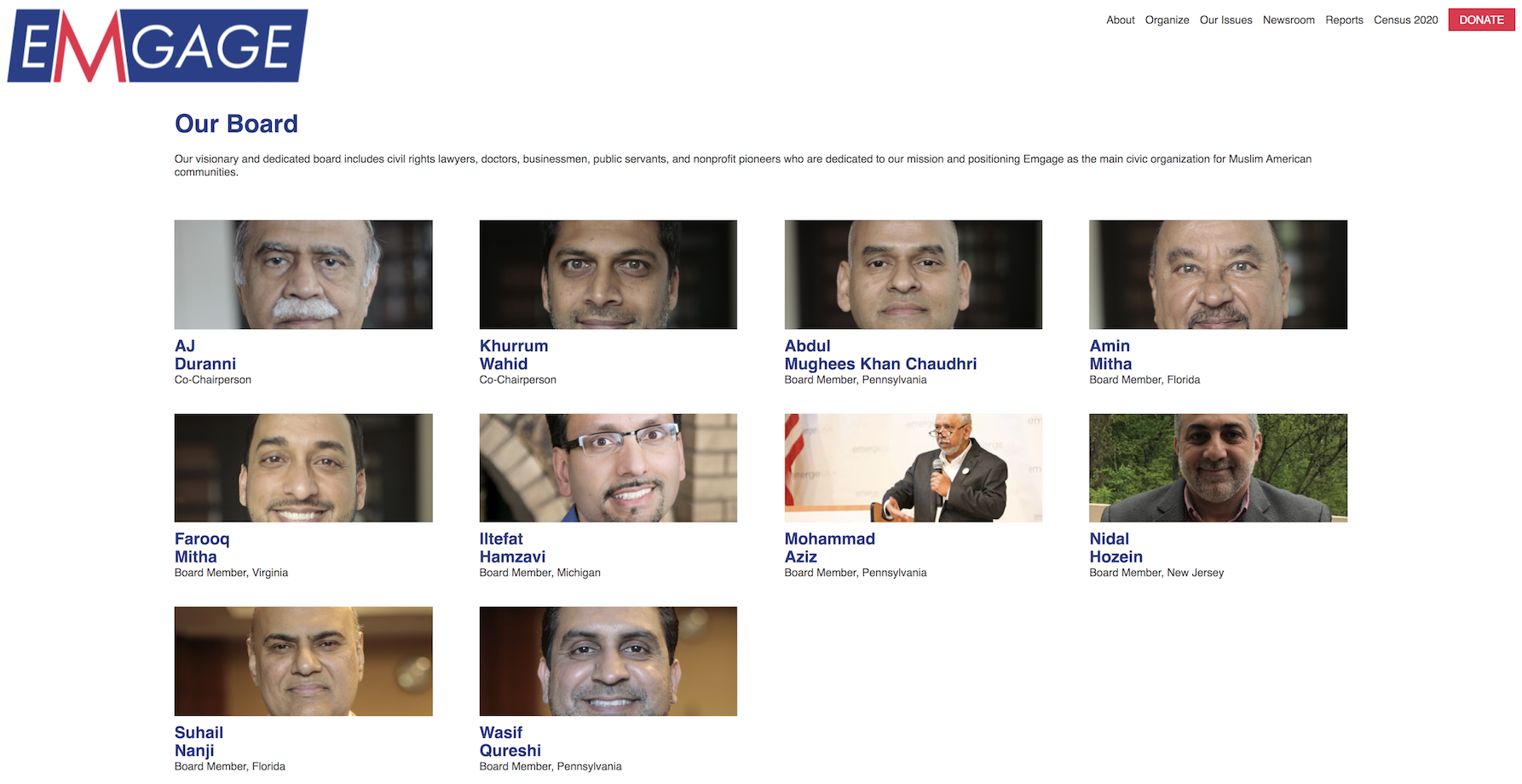

Formed in 2006 by two Muslim lawyers from Florida, Khurrum Wahid and Farooq Mitha, the organisation was initially known as the Center for Voter Advocacy - before it changed its name to Emerge and later in 2016 to Emgage.

As an organisation, Emgage is made up of three legal entities. Emgage Foundation focuses on "Get Out The Vote" and registration of voters. Emgage Action is meant to advocate for issues important to Muslims, such as political literacy and civic engagement, as well as pushing back on policies that hurt the community. And Emgage PAC purportedly supports political candidates that align with the values of the community.

Its governance is made up of a national board, with its six local chapters in Michigan, Virginia, New York, Pennsylvania, Florida and Texas, each governed by local boards.

In an interview with MEE in Washington, DC, in March, Wahid said the idea of the organisation really had its roots in the 2004 election between George W Bush and John Kerry. He said that even then, after the 9/11 2001 attacks and the Patriot Act, which created draconian counter-terrorism and surveillance powers that disproportionately affected Muslim communities, the stakes were seen as higher than ever before.

"We didn't have a mechanism in the community to engage the grassroots and get them to have a voice, and be part of the decision-making process," he said.

'If a million Muslims do vote, they will simply claim that they managed to get them all, which is simply not true'

- Sarwat Hussain, community organiser, Texas

Wahid reasoned that Muslims, making up around one percent of the population, were perceived as a liability in the political world.

"I wanted to change that. It was about getting respect back for this community," Wahid said.

One of the first fundraising events the new group organised involved Keith Ellison, then a Congressional candidate from Minneapolis. That event in 2006 gave birth to the first iteration of Emgage as a PAC, an entity allowed to raise funds for political candidates. It also helped Ellison become the first Muslim in Congress.

Ellison, now the attorney-general of Minnesota, confirmed Wahid's version of events to MEE.

Around 2008, the group focused on consolidating the Muslim vote for Obama.

Following the election of Obama, Mitha, who was previously a Fulbright Scholar in Amman, working on Jordanian-Israeli relations, and a partner at a law firm, joined the Obama administration as the special assistant to the director of the Department of Defense (DOD), in which he helped try to align small businesses with the urgent needs of the DOD.

From 2014, Emgage began to branch out of Florida, creating chapters in swing states where Muslim voters could make the difference between two candidates as their own bloc. In 2016, the group started its Get Out The Vote efforts across multiple states and received grant money.

Community activists from Florida and Texas who recall Emgage in the early days say the organisation spent much of its formative years networking with groups and organisations rather than organising at the grassroots level.

Several activists characterise Emgage as either trying to moderate the kinds of work being undertaken in the community, or controlling the visibility of other organisations.

Sarwat Hussain, co-chair of the American Muslim Democratic Caucus-National (AMDC-National), says she has been familiar with Emgage since 2012, and that her first interaction with the group's leadership involved her being told by an Emgage board member to downplay her "Muslimness".

"He told me 'don't be upfront about your 'Muslimness'. But it was the opposite of what we were trying to do. We were trying to show that Muslims were here to stay, to serve. I refused," Hussain, who is based in San Antonio, Texas, said.

Hussain, along with several other community organisers across the country, told MEE that Emgage board members also found ways to pit Muslim activists and political organisers against each other, often using existing tropes to demonise others' work. Following the fallout, they would attempt to bring in their own contacts to take over the roles.

She said once she recognised how Emgage operated, she and other organisers tried to steer clear of the group.

"They were always seen as trying to come in where work was already being done, and then claim the work as theirs," said Nadia Ghabin, a community organiser in Florida, who was approached in 2018 by Emgage to partner on voter registrations. She flatly refused.

Olivia Cantu, who worked for Emgage for four years before she was fired on 30 June 2020, confirmed that Emgage had a tendency to bulldoze its way over other organisations.

She said that though there were honest and hardworking individuals at Emgage trying to make sense of the political terrain, Emgage in Florida was run by "a shadow board," in which decisions were often made between the real powerbrokers outside of formal meetings.

Cantu, who started off as a volunteer at Emgage and moved up the ranks to become Florida operations director, told MEE she was not presented with a reason for her dismissal.

She assumes she was dismissed because she had refused to stop working with the Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC) on the issue of rising Hindu nationalism, after a certain Emgage board member felt the organisation was not financially benefiting from the work.

MEE has a copy of her submission to Emgage's human resources department shortly after her termination. Emgage did not respond to MEE's request for comment on why Cantu was dismissed.

Emgage under Trump

Though it is unclear what Emgage achieved before 2016 as an organisation, and there is a very thin digital footprint of the organisation's achievements outside of its own website, there is a general consensus that, since the start of the Trump presidency, the organisation's profile has ballooned.

The election of Trump in 2016 saw a wave of progressive candidates running for local or district, state and Congressional office around the country. Emgage jumped on this wave, too, announcing it would support young Muslim candidates running for office.

The organisation supported and endorsed several Muslim candidates, including Congresswomen Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, as well as other candidates running for state legislatures, especially in swing states.

As part of a conglomerate of groups resisting Trump's racism, Islamophobia, xenophobia and white supremacist leanings, Emgage was able to raise its voice as part of a chorus of liberal outrage against the administration.

As a Muslim organisation closely tied to the Democratic establishment, Emgage focused on promoting itself as a rearguard defence of Muslim Americans, outspoken on causes with which the liberal establishment was comfortable and carefully tiptoeing around more difficult matters the mainstream had yet to reach consensus over.

Domestically, it spoke against the Muslim ban, on immigration and criminal justice reform. Following the murder of George Floyd, it condemned police brutality and anti-Black violence.

Where many progressives (and increasingly many young Muslim Americans) are in favour of Medicare For All and the Green New Deal, Emgage speaks vaguely about the "issues" of climate change and healthcare.

On matters of human rights abroad, it has stuck to positions that align with overall US foreign policy: the Rohingya in Myanmar, the Uighurs in China and, following the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the rise of authoritarianism in Saudi Arabia.

Since August 2019, Emgage has also raised, albeit more carefully, the crisis in Kashmir and the rise of Hindu nationalism in India.

But Emgage has never properly demonstrated how it reaches consensus as an organisation on a political issue, be it domestic or foreign policy focused.

Even as it styles itself to the Democratic establishment as a Muslim American powerhouse, it remains on the periphery of Muslim America's imagination.

And if it is barely known among South Asian and Arab Muslims, it is certainly not a part of the Black Muslim community. The national board is made up of predominantly South Asians and Arabs - and they are all men.

Wahid acknowledged that this was problem.

"We passed a resolution a couple of years ago, that decided that one third of the board had to be women by the 2020 election cycle" he told MEE.

MEE was not able to find any evidence of this resolution on their website.

"The founders are people with roots in South Asia, but they're not exclusive and are open to reaching beyond that community," Ellison, the attorney-general of Minnesota, told MEE.

"I'm a Black Muslim and I've never felt that they're exclusive or don't want to partner. They've always been kind and open to me. My experience with them has been positive."

Still, activists say hosting fundraisers for a Black politician does not mean being connected to the Black community.

Emgage's modus operandi on the ground, activists say, has been to rely on sweeping statements that promote it continuously as the "largest" and the go-to organisation for all things related to politics and the Muslim community, when it simply does not have the capacity or the legitimacy to undertake the projects it claims to lead.

"If you want to know if they are a grassroots organisation, no, they don't exist as one," said Ghabin, from Florida.

Hussain, who describes herself as a committed member of the Democratic Party, told MEE that organisations such as the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), the American Democratic Caucus, and others, had been conducting voter outreach for years and "wonders what Emgage means when they position their work as 'historic'".

"Promising a million votes for the Democratic Party is not an easy thing," Hussain says, adding: "If a million Muslims do vote, they will simply claim that they managed to get them all, which is simply not true."

Wael Alzayat, the CEO of Emgage Action, said allegations it didn't exist as a grassroots organisation were "not true".

"Our Million Muslim Votes summit was attended by nearly 2,000 members and grassroots supporters. Emgage currently has 24,000 members who have opted to receive our correspondence and/or actively donate to the organisation," Alzayat told MEE.

In March 2020, Wahid told MEE that Emgage had 5,000 members. MEE cannot independently verify how many members the organisation has or if its membership did increase five-fold in the past six months, especially given there is no indication of membership numbers in its annual reports.

But grassroot organisers say exaggerations have often seen Emgage tangled in its own spin.

In Wahid's letter to Muslim Americans last month, addressing his participation and that of three others from Emgage in MLI, the Muslim Leadership Initiative - a controversial scheme which, in part, brings Muslim Americans to Israel to study Judaism and Zionism - he tried to play down the impact four individuals might have had in an organisation made up of "100 staffers and national and local board members".

When MEE asked the CEO how many staff members Emgage had, Alzayat, in his reply on 23 September said: "23 employees, 20+ seasonal organisers, and over 400 volunteers".

Emgage has promoted itself as indispensable in getting Muslims out to vote. In doing so, it has released a series of stats and reports illustrating how Muslims came out to vote as a result of its efforts. The only problem is that Emgage cites only its own research as proof of impact, rather than any independent studies.

For example, according to a 2019 report published by Emgage, its "Get Out The Vote" efforts contributed to a 22 percent increase in voter turnout during the 2018 primaries in Florida.

But the report makes no attempt to explain how it reached the conclusion that its efforts led voters to the polling station. Nor does it acknowledge that there are multiple organisations doing the same work, and that overall voter turnout in the 2018 midterm elections was the highest of any midterm election in more than 100 years.

In explaining the methodology to MEE, Alzayat says:

"We conduct our 'Get out the Vote' work by engaging likely Muslim voters who are in our voter database, then we review the files of those voters after the election to see whether they voted or not. This enables us to measure voter turnout and impact of our work, especially when we compare it to historical records."

He continues: "Given our extensive work in this area and partnerships with local and national organisations, we take care to develop engagement strategies that allow the various organisations to focus on specific geographic areas. Without a doubt, many organisations (Muslim or otherwise) play a role in increasing voter turnout and whatever success that we are witnessing is a shared one.

"But Emgage is proud to conduct the largest number of phone calls, send out text messages, and place social media ads that target Muslim voters on a national scale."

Text messages and phone calls have become a staple of the group's work. In a mass email sent out by Emgage on 28 September, reporting on its progress in getting a million Muslim votes, Alzayat writes in the subject line: "1.7 MILLION Contacts With Muslim Voters"

"We took on a very big task with our commitment to turn out one million Muslim voters this November. But with the help of our supporters like you, we have accomplished incredible achievements to make our voices heard. So far, our efforts include sending 1.2 million text messages and making 500,000 calls. And we are just getting started!" he wrote.

Cantu says the claims that text messages and phone calls actually make a difference is flawed. Phone calls are a hit and miss. During election season, Americans are text-bombed by campaigns, resulting in text message fatigue.

"I have witnessed these phone banks. If they make 30 dials, they actually have one conversation," Cantu said, adding that, as someone who worked in Florida, she always found claims Emgage had that much influence over the Muslim community to be extremely exaggerated.

"I actually wondered: where are they getting these numbers from?"

Ghabin says there are deeper holes in Emgage's claims regarding its impact on the 2018 midterms in Florida.

In Tampa Bay, inside Hillsborough county, where Emgage claims to have helped raise voter turnout by 22 percent, Ghabin says the organisation was not allowed to operate at the two largest mosques where voter engagement, including registration, traditionally takes place.

"They had no presence and nobody knew them. But they came in wanting to use our existing relations with the community to sign up voter registrations. But the mosques didn't want them because they knew of their links with MLI," Ghabin says.

Cantu, the former Emgage employee, confirmed Ghabin's claims that Emgage is often turned away from mosques in parts of Florida.

"Besides one or two mosques, they are simply not welcome at others," she said. Emgage did not respond to MEE's requests for comment on this specific matter.

From Bernie to Biden

In February 2020, Emgage endorsed Bernie Sanders, then among the frontrunners in the race for the Democratic nomination after a succession of strong performances in the early primaries.

Sanders had addressed the Islamic Society of North America's (ISNA) conference in 2019 and was well regarded in Muslim communities, and to have endorsed any other candidate at the time would have been a strategic blunder.

Emgage's endorsement of Sanders did endear Muslims otherwise sceptical of Emgage, but this was short-lived.

Just four days before endorsing Sanders, Farooq Mitha, the co-founder of Emgage, held a fundraiser for Biden, highlighting what commentators and observers say is part of a pattern of contradictions by the organisation.

It is unclear why the Sanders' campaign made a point of highlighting Emgage's endorsement, given that other organisations, such as the Muslim Caucus of America, had already endorsed him almost 20 days earlier. More importantly, there was very little about Emgage - its leadership or its agenda - that actually was in sync with Sanders and his left-wing agenda on healthcare, inequality, or the economy.

And whereas Sanders might have said it was "an honour" to receive an endorsement from Emgage, community organisers note that in reality it was Emgage that benefited from the visibility created by Sanders.

Faiz Shakir, Sanders' campaign manager, did not reply to MEE's question as to why Emgage was seen as an important endorsement for Sanders' presidential campaign.

More contradictions were to come.

In March, the Biden campaign came under intense pressure after it was revealed that its Muslim outreach coordinator was a vehement supporter of India's right-wing Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Amit Jani, who had been appointed in late 2019 as Biden's Asian-American Pacific Islander (AAPI) outreach coordinator, also had the Muslim community in his portfolio.

Who is Amit Jani and what is his relationship with Indian PM Narendra Modi?

+ Show - HideAmit Jani is political operator from New Jersey. He previously worked for New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy's 2017 campaign as well as Senator Bob Menendez's 2018 campaign. He then moved to Governor Murphy's office before joining the Biden campaign in September 2019 as his Asian-American Pacific Islander (AAPI) national vote director.

Jani's appointment drew outrage among Indian Muslims in particular who pointed out that his family have a long relationship with India's right-wing BJP government, the Hindu-paramilitary organisation known as the RSS, as well as Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Jani's late father, Suresh, reportedly came from the same village as Modi, and they has originally met at an event organised by the Hindu paramilitary organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

Suresh later became one of the founders of Overseas Friends of BJP (OFBJP) in the United States, and the family hosted Modi at their home in New Jersey in 1993.

Jani is an avid supporter of Modi. In 2014 blog published on Huffington Post, Jani compared Modi to former President Barack Obama.

"Modi and Obama have brought fresh voices and creative ideas to their governments, after many years of having increasingly unpopular and disconnected leaders in office. What I find most impressive amongst both leaders’ backgrounds is their humble upbringing and their ability to connect with the middle and working classes."

Following the re-election of Modi in 2019, Jani posted images on Facebook celebrating the BJP's victory and following Indian government's revokation of Kashmir's semi-autonomy, Jani was listed as an organiser for an event honouring the development.

He has never disavowed his relations with Modi or the BJP.

Under pressure, the Biden campaign turned to Emgage's Mitha, who had in 2016 become the Muslim outreach director for Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign, for assistance. He eventually took on the role.

This meant that in March, Emgage was endorsing Sanders even while its co-founder was the Muslim outreach coordinator for Biden.

According to Emgage, an informal survey of the organisation's members and email list users found nearly 75 percent of its members supported Sanders.

"From where we're sitting and what we've seen, it doesn't seem that any major candidate has reached out in the same way," Alzayat said of Sanders.

But when Biden became the presumptive nominee in April, Emgage immediately endorsed him.

Given that endorsing Trump was not an option for most Muslim Americans, the immediate endorsement of Biden felt to many as if Emgage had in effect relinquished the desire to make Biden work for the votes it claimed it could help win. And in doing so, Emgage expected the Muslim American community to immediately fall into line, too.

"They became his spokesperson," Hussain says. "And the Biden campaign got the token Muslims who wouldn't raise difficult topics."

Mitha was subsequently referred to in the mainstream media as Biden's Muslim outreach manager and Emgage began representing itself as the Muslim organisation with access to Biden, releasing exclusive comments from Biden to the media and co-hosting events, without ever mentioning that its co-founder and board member was the go-between.

As part of a cohort of questions sent to Biden prior to endorsement, Emgage asked the former vice-president to list "Muslim or minority groups and leaders" that had endorsed him.

"I am proud to have the support of Farooq Mitha, Emgage PAC co-founder and board member, Dilawar Syed, Emgage PAC board member, and Mallak Beydoun, senior official, Office of Mayor Duggan, Detroit," Biden said, before mentioning others.

According to Emgage, Mitha had sent a note asking for a leave of absence in February 2020. But Emgage's staff page listed Mitha as a board member until the page was taken down in September 2020.

Neither Mitha nor Emgage responded to MEE's request for written proof that his period of absence began in February 2020.

Emgage and the ADL

Since the Electronic Intifada accused Emgage of being a pro-Israel outfit, concerned Muslim Americans have been reaching out to the organisation to seek clarity on its relationships with other groups outlined in EI's expose.

For its part, Emgage released a statement on its recently created Medium page, rather than its official website, in which it affirmed "its commitment to Palestinians" and addressed what it described as "false claims".

But Emgage did not address allegations that it had links with the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a pro-Israel organisation that in August was the subject of an open letter signed by more than 100 activist groups accusing it of "a history and ongoing pattern of attacking social justice movements led by communities of color, queer people, immigrants, Muslims, Arabs, and other marginalized groups, while aligning itself with police, right-wing leaders, and perpetrators of state violence".

When the outrage did not abate, Wahid addressed the Muslim American community in a letter posted on the Emgage website. In his attempt to quell the rising anger, Wahid chose to mitigate the issue by explaining that Emgage had no "programming" with the ADL. Emgage now has a section on its website, called "Fact and Fiction about Emgage" that says the organisation has no formal links with the ADL.

But in March, in an interview with MEE, Wahid spoke candidly about Emgage and the ADL, characterising the relationship with the ADL as "transactional":

"With the ADL - what folks don't realise, and being a criminal defence lawyer, I know - is that in the judicial world, in the world of law enforcement and judges, the ADL has a very loud voice, and if you are not engaging them on some of these issues, you are ceding that territory and you are allowing them to put misinformation out to law enforcement and judges who make decisions about those who come before them."

To illustrate his point, he cited two examples in which Emgage had worked with the ADL.

"There was an anti-Sharia bill coming up in Florida [in 2014]. We had beaten it back three years in a row. In the fourth year, it seemed to have enough momentum that it was going to pass," Wahid said.

"The language was very problematic. So we built a coalition. Part of the coalition was the ADL."

Wahid says the ADL had joined the coalition because a portion of the proposed bill would have impacted the Jewish community.

The amended bill did pass but, he says, they "were able to knock the teeth out of it".

The second time they worked together followed the ADL publishing a report in which it characterised certain incidents as "Muslim terrorism".

Wahid said he had met with the ADL over the report and had pushed back on the issue, resulting in the two organisations having a sustained dialogue on similar issues.

"So before they would push some of these things out, they would have conversations with us, to get our viewpoint. And in some of those situations, it meant they decided no, its not appropriate to include this particular incident as so called 'terrorism'. On other occasions, they didn't listen to us and they did what they were going to do," Wahid said.

"But at least we were having some dialogue and some positive impact.

"The ADL is not going anywhere... We have to engage them on a certain level, it doesn't mean we are partnering with them [and] we are not allies in all that we do, but to the extent that we can continue a dialogue with groups such as that, that aren't going anywhere, and that have a very profound impact on criminal justice... it is important for us to look out for our community and engage."

Wahid said he understood that the optics of working with the ADL was problematic but "sometimes substance has got to take priority over the optics".

"Sometimes when you lead, you're stepping into a space that others aren't willing to follow."

He added that Emgage would work, within limits, with any organisation, including the police and elected officials who don't agree with the community, if they felt that that engagement could help improve integration, equality and opportunity for Muslim Americans.

"And whether or not we get tarred by some in our community as being the so-called Uncle Toms in our community, I don't think that is our primary driver."

Wahid's perspective cuts to the heart of a culture war playing out in the US in which there is an increasing schism between those who say they are willing to open dialogue with "problematic" organisations and individuals, and those who believe that engaging with organisations actively working to demonise or assail your community is untenable.

Over the past month though, Emgage staff have embarked on a project of scrubbing their websites and profiles of connections with work linked with the ADL or AIPAC (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee lobbying group).

Until September 2020, Wahid's profile on his own law firm website described him as a member of the ADL civil rights committee in Miami. This has since disappeared. Alzayat told MEE that Wahid left the position in 2018.

Emgage, MLI and faithwashing

The Muslim Leadership Initative programme has been a major point of contention in the Muslim American community ever since it was first launched in 2014.

The programme, formed by Abdallah Antepli, a Muslim chaplain at Duke University, and the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America, an Israeli think-tank, attempts to position the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a dispute between two religious groups. The MLI project involves academic study and a trip to Israel in which Muslim American "leaders" are given an opportunity to learn more about Judaism and Zionism.

Palestinians, in particular, have opposed the programme, calling MLI a "faithwashing" project for its attempt to recast Israel's ongoing settler-colonial project as a religious conflict between Muslims and Jews, a conflict that has "two sides". Moreover, Palestinians have repeatedly argued that participating in the project would contravene the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign, and further efforts towards "normalisation" with Israel.

Alumni of the MLI programme have gone on to narrate their "re-education" as Muslims confronting the Israeli-Palestinian crisis in TIME Magazine and The Atlantic.

At least four people within Emgage, including Wahid, are alumni of MLI.

Following Electronic Intifada's resurrection of these MLI skeletons, Emgage purportedly tried to clarify that as, an organisation, it never had a relationship with MLI, but individuals had travelled in a personal capacity - and that it had since adopted a policy that prohibited members of Emgage from participating in the programme.

But, even here, basic details about this resolution are not particularly clear.

In March, Wahid told MEE that the community response to MLI had compelled them to pass the resolution that banned board members from participating in the Zionist normalisation programme.

On 3 September, Emgage said in a statement that the resolution applied to board members, staff and committee members, and was passed in 2018.

In his letter addressed to the Muslim community on 16 September, published on Emgage's website, he wrote the resolution was passed in February 2019.

Emgage did not respond to MEE's request for the minutes of the board meeting to ascertain when the resolution was passed.

Observers note the resolution that was supposedly passed in 2018 or in 2019 was also never made public, until it was uploaded in September 2020 as an unlinked and near-undiscoverable document on the site.

But those familiar with the wider concepts of faithwashing say Emgage is engaging in semantics when it insists the MLI programme was always outside the ambit of the organisation.

In other words, even if Emgage no longer allows staff or board members, even in their personal capacity, to take part in programmes like MLI, those who have already participated in MLI remain still on staff, on the board, directing the activities of the organisation. Moreover, the organisation has yet to disavow itself from the pro-Israel, faithwashing ecosystem in which it has resided for much of its existence.

Emgage's insistence that it has no joint work with Zionist organisations is also not entirely accurate, given the individuals and organisations it welcomes into its orbit.

For instance, in 2018, at its annual policy conference, titled "Upholding our Values: A Commitment to Tolerance," Emgage hosted Robert Silverman, then-US director of Muslim-Jewish relations of the American Jewish Committee, as a guest.

Explaining his role at the AJC in 2016, Silverman said that part of his role was "to move beyond nice discussions and interfaith gatherings at a local level".

"They are uplifting and important and there's quite a bit of Muslim-Jewish engagement going on. But we've got to scale it up to form real networks to do policy advocacy on a national level," he said. "We will also work on a better understanding of Israel among Muslim Americans."

Earlier this week, the same Silverman wrote in support of a new bill in the Senate that promotes normalisation with Israel.

Despite the obvious, often public and unapologetic agenda of these faithwashing engagements, Emgage remains represented, through Alzayat, at the Muslim Jewish Advisory Council, a project between the AJC and the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) which, incidentally, began around the same time as Silverman's appointment.

'Good Muslims'

But Emgage has bigger ideological problems to confront than interfaith trojan horses.

Several activists point to Alzayat's career as emblematic of the organisation's tendency to cheerlead some of the most conservative elements of American foreign policy.

Alzayat routinely points to his position as a senior adviser to Samantha Power, the former US ambassador to the UN, but before this, he held several positions in Iraq during the American occupation of the country.

The first was as the Provincial Affairs Officer for Anbar Province at the US embassy in Baghdad in 2007-8.

Alzayat "provided policy and operational guidance to Provincial Reconstruction Teams in Fallujah, Ramadi and al-Asad" during "the Surge," when then-president George W Bush sent additional troops to Iraq to quell a spike in violence. "The Surge" had catastrophic implications for Iraq. Alzayat also worked on the Egypt desk, as well as for the US ambassador to Iraq during the US military withdrawal.

Though Emgage has no policy on Iran, Alzayat is also known to invoke Israeli talking points when speaking on Iran.

In 2017, Alzayat wrote for the Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP), a group linked to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, which pushes neoconservative US national interests in the Middle East: "The US has tried the other 'resorts' already, with the Obama strategy of building on the Iranian nuclear agreement and then Secretary of State John Kerry's shuttle diplomacy on Syria to restrain Iran by accommodating Iranian and Russian interests without recourse to force. This strategy has failed.

"Consequently, the Administration needs urgently a comprehensive approach toward Iran, centered in Syria and Iraq, including military means, to restore regional stability. Otherwise, new disasters, fueling extremism and likely new WMD programs, will emerge."

Whereas Alzayat's name was listed on WINEP's website as an expert as recently as August, this has since been removed from their site.

WINEP did not reply to MEE's request as to why his profile was scrubbed from their site.

In July 2020, during a discussion on Biden's Israel-Palestine policy on Israeli channel i24, Alzayat, identified as CEO of Emgage, said "while [Biden] does not support conditioning aid to Israel - as an ally in the region - a region that, you know, has Iran and [Syrian dictator] Bashar al-Assad, and all of these unhelpful actors, but he is troubled and he has said that he will oppose the annexation of the West Bank".

For decades, US foreign policy in the Middle East has pivoted around Israeli interests, and Alzayat's approach to the Israel-Palestine conflict appears little different.

In a later question about Biden's policy that would not reverse Trump's decision to move the US embassy to Jerusalem, Alzayat prefaced his answer with: "We welcome the affirmation of the Jewish people's right to have an embassy- not an embassy- but a capital in Jerusalem," before going on to say that Biden's policy was "contradictory," because "it does not mention the Palestinian rights and aspiration for at least East Jerusalem".

Emgage repeatedly says it opposes "Trump's decision to move the embassy to Jerusalem," so it is unclear who Alzayat speaks for when he welcomes "the right of the Jewish people to have a capital in Jerusalem". Emgage also repeatedly describes the US embassy move as "Trump's decision". It is also unclear if this will change, given that Biden made it abundantly clear that he has no intention to move the embassy back to Tel Aviv, endorsing Trump's decision.

Alzayat's comments suggest Emgage has endorsed it, too.

Observers note that this exchange is a prime example of how Emgage operates and engages with power.

Alzayat's passing reference to "the Iranian threat" in a discussion about Biden's conservative approach to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict also speaks directly to the establishment, and clearly views the rules of engagement through the lens of US and Israeli foreign policy.

"I am not sure why some people think they can 'reform' this organisation when it is led by these types of people," one prominent Muslim-American activist, who asked not to be named, told MEE.

Likewise, Samia Assed, an activist from New Mexico and a Democratic Party delegate, told MEE that tokenised engagements such as MLI and MJAC had paved the way for "good Muslims" with whom Israel, the US power base, and their proponents, are happy to negotiate.

"As a Muslim American organisation they still haven't said 'Zionism is racism'. This should be normal for a Muslim organisation," said Assed. "There are Jewish organisations that are anti-Zionist. Why can't Emgage commit to that?

"Emgage also say they support BDS as an American right, but they haven't said 'you should boycott an illegal occupation'."

"They have to step up, or step away. It is as simple as that."

She says MLI divided the Muslim community, misrepresented the Israeli occupation, and turned ordinary demands for Palestinian human rights, dignity and self determination into "unreasonable" and "radical" positions.

"It is clear they made these concessions when they went into these partnerships. And there is almost a disconnect when you call them out on BDS. It is as if they don't know what you are talking about," Assed said.

"There is an obvious type of grooming that keeps them out of the mainstream concerns, the everyday concerns of Muslims on the street," Assed added.

Activists are particularly worried now that Emgage is coordinating the hiring process of Muslim staffers in a potential Biden presidency.

"The big problem with Emgage is that they have primed themselves for these big leadership roles, but they skipped over the grassroots organising, and the work and the familiarity to the concerns of people on the ground." Assed says.

Nazia Kazi is an associate professor of anthropology at Stockton University in New Jersey.

"These figures offer the guise of interfaith dialogue, Muslim visibility, or the chance to have a 'seat at the table' as a gloss for alliances with the state," she said.

"In my book, I write about 'US Empire's Good Muslim Cheerleaders'. By this, I mean the ranks of Muslims who silence, sidestep or disregard tackling the most egregious elements of American imperialism in exchange for visibility and legitimacy in the US racial order.

"I remain unsurprised at the cadre of Muslim Americans eager to step up in defence of US empire-building," Kazi adds.

Endorsing pro-Israel candidates

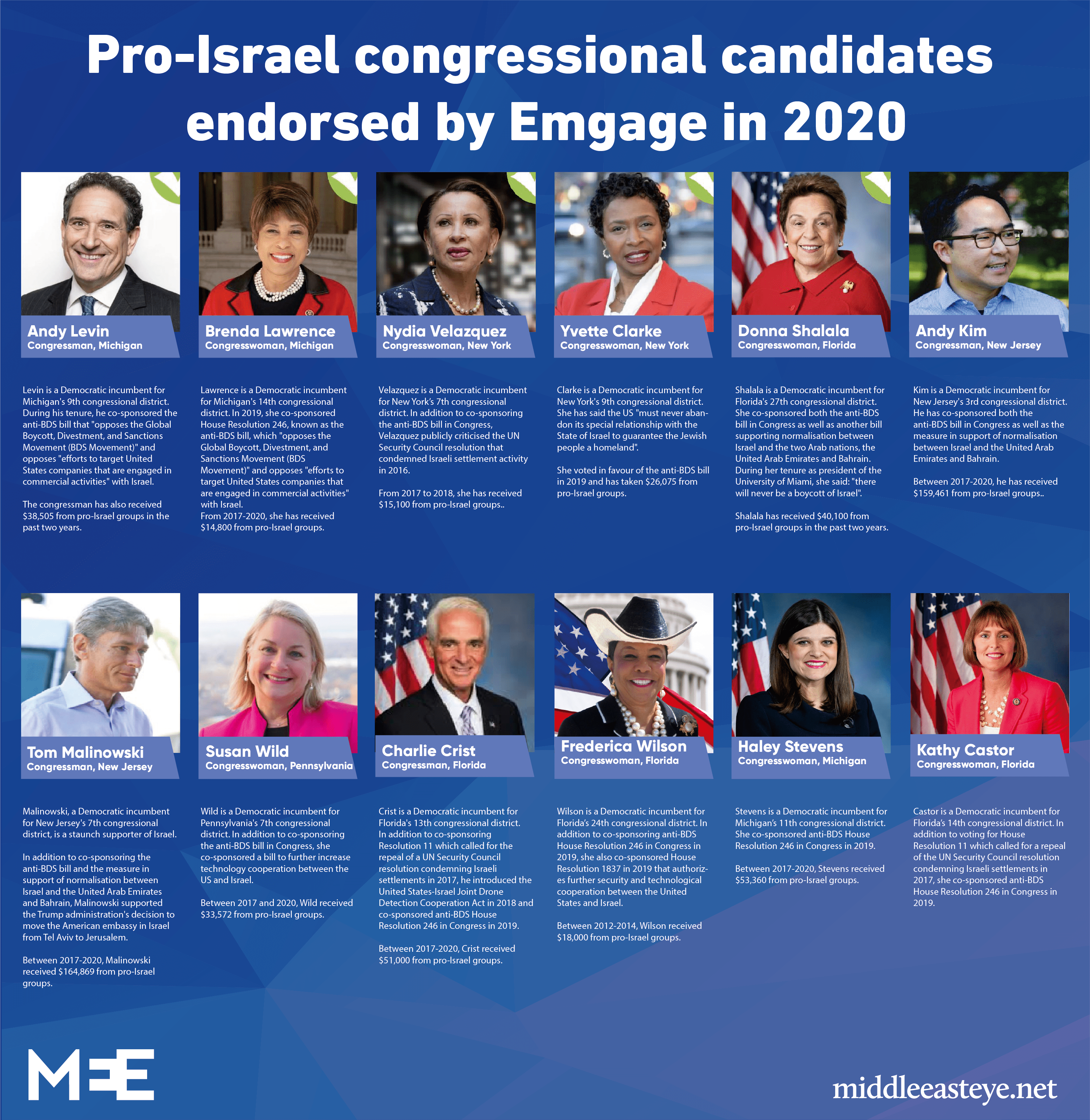

Middle East Eye has found that Emgage has endorsed at least 20 pro-Israel candidates competing in November's elections, calling into the question the organisation's agenda and vetting process.

Out of the 41 congressional candidates endorsed by Emgage in 2020, MEE found at least 12 Congressional incumbents who co-sponsored or voted against the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions Movement (BDS) in Congress in 2019, had taken multiple sponsored trips to Israel, and collectively received upwards of $621,697 from the pro-Israel lobby since 2017.

In this election cycle, Emgage has endorsed more than 50 candidates across 10 states running for city council, state legislature or Congress.

Emgage has also endorsed candidates such as Robert Wittenberg, a state representative from Michigan who co-sponsored an anti-BDS bill that in 2016 made the boycott of Israel illegal in Michigan. Tom Malinowski, a Congressman from New Jersey, who openly supported the US embassy move to Jerusalem, has also been endorsed by Emgage, with its PAC contributing $1,500 to Malinowsky's campaign in 2018.

According to Wael Alzayat, CEO of Emgage, the organisation assesses "candidates based on their history of engagement with the Muslim community, their viability as a candidate, their positions on issues, and track record".

But he did not respond to queries as to how endorsing candidates that oppose BDS or support the embassy move to Jerusalem fit in with the organisation's values.

Emgage has tried to present the personal politics of its board members, such as the MLI trips or personal relations with the ADL, as separate to the goals of the organisation, but positions taken by Emgage, community organisers say, are more often than not categorically linked to the worldview and agendas of its most visible leaders.

It is the board members' personal relationships that have provided Emgage with access to elite political spaces as well as greater amplification in the media.

And when these engagements buttress with Emgage's endorsements of openly Zionist candidates for state legislature or Congress, community organisers and scholars say Emgage's pursuit of a seat at the table often really means endorsing policies that contravene community sentiment. The endorsement of pro-Israel candidates cannot be seen as independent to the group's cultural and political proximity to the MLI, the ADL and the AJC.

The latest revelations come as Muslim Americans come to terms with an alleged attempt by several Muslim organisations to shield it from criticism following the publication of the Electronic Intifada expose.

The article set off a firestorm among community activists already deeply concerned by Emgage's rising influence and dissatisfied with their purported control over matters of importance to the Muslim community within the Biden campaign.

On 10 September, a group of activists and scholars wrote an open letter to mainstream Muslim American organisations, including the Council for American Islamic Relations and the civic action group MPower Change, currently working with Emgage in the "Million Muslim Votes" initiative, to cease all relations with the organisation.

But Muslim civil and political advocacy organisations have been hesitant to condemn Emgage in public.

Behind the scenes, in WhatsApp groups and email listservs, a battle is raging between progressive Muslim activists, establishment Muslim Democrats, as well as some older organisers in the community over how to proceed with their relationships with the organisation.

Whereas younger activists, many of whom are Bernie Sanders supporters, are calling for immediate action, those working with Emgage claim that any criticism of their work so close to the election "is an act of voter suppression".

Meanwhile, other activists have urged the community to prioritise dethroning Trump.

But the ambiguity from leading Muslim American organisations has also been compounded by the recent unveiling of an alleged "pact" between a group of Muslim organisations calling on each other to protect themselves from attacks, and has raised the spectre of a culture of unaccountability and lack of transparency among Muslim American organisations.

'Mutual defense pact'

According to an email seen by MEE, a day after the petition urging organisations to #DropEmgage was created, Abbas Barzegar, CAIR's national research and advocacy director, wrote to a group of Muslim organisers urging them to "activate a mutual defense pact".

"We need to coordinate to help our brothers and sisters at Emgage. Legitimate political critique is spiraling into destructive action that threatens our entire community," Abbas wrote in the email.

"We said this was effectively a mutual defense pact. We need to make good on it."

For many activists, the email served as proof that the lack of definitive action by leading Muslim organisations, as well as the tacit defence of Emgage on listservs and private WhatsApp groups, was part of a coordinated attempt to mute any public critique of the organisation.

Despite the pressure exerted on the Muslim organisations, the vast majority have steered clear from the topic.

Earlier this week, the US Council of Muslim Organisations, which Emgage joined in 2019, said that it had been working over the past month to investigate the concerns raised about Emgage.

"Despite strong efforts by everyone involved and some progress, we were not able to reach agreement. As a result, Emgage is no longer a member of USCMO."

Shortly after USCMO's statement was released, Alzayat wrote on his Facebook page: "We were not kicked out. Emgage resigned. This organisation doesn't get bullied."

But it is unclear why USCMO had allowed Emgage to join their council in the first place.

Oussama Jamaal, USCMO's secretary-general, initially agreed to talk to MEE but subsequently did not return MEE's calls.

Barzegar, for his part, has insisted that despite there being a pledge among the organisations "to help protect each other from Islamophobic attacks from right-wing extremists," there was "no mutual defense pact".

He told MEE that his email was not an attempt to quell open critique of Emgage.

Barzegar said the listserv he had sent it to was called the Muslim Civic Engagement Table (MCET), a loose grouping of representatives of Muslim organisations, including CAIR, MPower Change, MPAC, Poligon and others, who had decided in early 2019 to pool resources towards getting more Muslims out to vote.

He also said he sent the email in his personal capacity - even though he was on the group as a representative of CAIR.

MEE has not been able to independently ascertain the extent of coordinated efforts to protect Emgage. However, none of the lead organisations on MCET or its leadership have spoken publicly about the serious allegations pitted against the group.

Barzegar's email also followed an incident in August - in which CAIR edited out comments critical of Emgage from a video featuring Palestinian scholar and activist Sami al-Arian.

Al-Arian, a former political prisoner in the US who was eventually deported to Turkey, had described Emgage as "trying to infiltrate the community".

"We need to speak about this and not allow those people who have [an] agenda that aligns with Zionist imperatives in America and make them a spokesperson for us," he said. "I think our people need to wake up and stand up for justice. We are not going to be empowered by simply kissing the hands - or the behinds - of the people in power today."

Barzegar tendered his resignation in late August and left CAIR at the end of September.

Samia Assed told MEE that several organisations might have been driven by the Muslim community's inclination to "give people the benefit of doubt".

"There might have been internal talk about bringing them in and educating them. I can see how that is tempting," said Assed, who admitted she was open to working with Emgage before she read the Electronic Intifada piece in early September.

"I didn't know the extent to which they were involved with things like MLI, because they kept on distancing themselves, and they kept on saying they support Palestine, but the paper trail now shows otherwise," Assed, who signed the open letter against Emgage, said.

As a PAC, Emgage is not a very large or influential one. In the 2020 election cycle, Federal Election Commission (FEC) filings indicate it has made contributions totalling $20,000 to no more than five candidates. It has instead focused on demonstrating support and facilitating fundraising events for candidates.

But since 2016, Emgage Action has received funding from the Open Society Foundation, culminating in a $1 million grant in 2019 to support, in part, their "Get Out The Vote" efforts. According to its 2018 annual report, 69 percent of its budget came from grant money, further exemplifying its disconnect from the community's grassroots.

Emgage's access to this grant money, as well as other resources, such as voter data, also appears to have compelled older and more established Muslim organisations to keep working with it. MEE has not been able to independently verify if this is the case, and if so, why other Muslim organisations have not been able to access this data.

MEE also understands that CAIR and MPower Change in particular, had agreed to work with Emgage and MPAC following a consensus among the Muslim Civic Engagement Table that they would steer clear from initiatives that threaten the Muslim community, specifically the Muslim Leadership Initiative, Countering Violence and Extremism programme (CVE) and the anti-BDS movement, seen as non-negotiables in the Muslim community.

"When they agreed to sign on, it was more likely that CAIR thought the group would be activated to defend them, given the number of attacks they face by Islamophobic groups, and not the other way around," a community leader familiar with MCET said.

A senior member in CAIR confirmed to MEE that they had decided to work with Emgage, "because they thought [Emgage] could change".

But Ahmed Bedier, a longtime community organiser in Florida, told MEE that, ultimately, Muslim American organisations would have to own responsibility for their part in the episode.

"Emgage derive their legitimacy from their proximity to power - and the critical thing here, though, is they would not have managed to secure this legitimacy with Biden if they hadn't managed to secure partnerships with the USCMO and other established Muslim organisations.

"Everything changed for Emgage when they managed to persuade a 25-year-old established national organisation like CAIR to come under their 'million Muslim vote' campaign," said Bedier, who hosts a weekly radio show on Tampa NPR affiliate WMNF.

"This gave them an entirely different level of legitimacy with the Biden campaign, and they turned around and used that access to power to push themselves onto and gain legitimacy with a community that didn't know them."

The executive branches of Mpower Change and CAIR declined to comment on Abbas' email.

Poligon and MPAC also did not respond to MEE's request for comment, while MPAC has continued to demonstrate public support for Emgage.

Brown skins, white masks

With less than a month left until November's elections, tensions and anxieties over a second Trump presidency are overflowing.

For many within the Muslim community, the idea of Trump returning is unimaginable.

The so-called Muslim ban, in its different iterations, has split families, destroyed livelihoods and set back communities emotionally and psychologically. Trump’s courting of white supremacists has seen a rise in hate crimes and xenophobia. Indian-American Muslims look at Modi's second term - in which he introduced anti-Muslim citizenship laws, and abrogated the semi-autonomy of Kashmir - and wonder if a Trump second term could see their naturalisation revoked, or more Muslims banned from the country.

Trump's volatility is fodder for a nervous imagination.

And yet, Biden's campaign has yet to provide any real comfort, either.

In June, Palestinian American activists staged a virtual walkout of a meeting with Mitha over the campaign's approach to Palestine.

"We are being told we should be grateful that Biden is even recognising the Palestinian conflict. This is not how you get people to believe in your candidate," said one of the activists who walked off the call.

Likewise, over the past six months, Indian-American Muslims in particular have tried to engage Mitha and Emgage about their concerns that his colleague Jani, a longtime supporter of Indian PM Modi, was organising within the Asian community, including Indian and Pakistani American Muslims.

In August, some among the Pakistani-American community were jolted when they realised their independence day event with the Biden campaign had been organised by Jani. Multiple sources have told MEE that Mitha has repeatedly downplayed their concerns, defending Jani and describing him as a friend.

Whereas Muslim Americans are gradually being told in off-the-record briefings that Biden's policy on Palestine is "not where we want it" but "it's better than Trump," both Mitha and Emgage have yet to acknowledge that the Biden campaign continues to have a supporter of Hindu nationalism on his staff.

That Indian-American Muslims have been not been able to ascertain whether Mitha's defence of Jani stems from the fact that Mitha's role may still be an unpaid, stop-gap measure from the Biden campaign and that he might actually still be reporting to Jani is only grating them further.

Neither the Biden campaign nor Mitha responded to MEE's request for clarification either.

"I will vote for Biden. But we also know they aren't serious about us. It will be like drinking poison," one Indian-American Muslim organiser who has heard Mitha recount different versions of his relationship with Jani, told MEE.

"And it's only because a Trump second term could end up being disastrous for us. Look what Modi did during his second term. Who knows, Trump could reverse naturalisation, and then what will we do? We can't afford it. We have no choice. And Mitha knows that," the organiser said.

Several Indian-American Muslims from New York City and cities in Texas have expressed frustration with Emgage over its slow response to their demands to stop facilitating campaign funding to Sri Preston Kulkarni, a congressional candidate in Texas, who has reportedly accepted tens of thousands of dollars from Hindu nationalists in the US.

Emgage had endorsed Kulkarni in 2018, but, following vehement pressure from the community this year, they decided against endorsing him ahead of the elections in November.

Alzayat told MEE that Emgage had not been made aware in 2018 that Kulkarni had received funding from the Hindu right wing in 2018, despite community activists from Texas claiming otherwise. Kulkarni did not respond to MEE's request for comment.

"It is unacceptable for any Muslim organisation to support candidates that take money from Israel or pro-Modi supporters," Sarsour from MPower Change told MEE, declining to comment further on the ongoing controversy surrounding Emgage.

But as the criticism mounts, Emgage's leadership and its surrogates continue to insist that complaints against the organisation so close to the election amount to a vote for Trump.

"The ongoing attacks attempt to cast doubt about the fidelity of Emgage and the largest voter mobilisation effort in Muslim American history," Alzayet said.

"If enough voters are convinced that this effort is somehow nefarious, enough of them may stay home and not vote in November."

Assed, the Palestinian American activist from New Mexico, said the assertion that criticising Emgage amounted to suppressing voters was "an act of voter suppression itself".

"It is a very pathetic argument. I am a member of the Democrat Party, I am organising day-in-and-day-out against Trump and fascism and white supremacy. Emgage can't use that card to defend their alliances or partnerships with Zionists to hush up Muslim voices. This is in fact voter suppression," Assed said.

Alzayat's argument, though, is on repeat, in private circles, among members of organisations such as CAIR, too, who insist that they will hold Emgage and Biden accountable after the election.

They are being recycled in other circles, by Muslim Democratic Party operators displaced by Trump's victory in 2016, and mainstream Muslim pundits, who see Emgage as their ticket to a White House iftaar.

None of the activists who spoke to MEE said they would vote for, or encourage others to vote for, Trump because of Emgage.

MEE has also found no data to back up claims that critiquing Emgage would result in a lower Muslim turnout.

Assed says the difference of opinion is really the story of two very different approaches to American power and the Muslim place inside America.

"Some of us want American politicians - whether Democrat of Republican - to know exactly what we want. We don't want to present a washed down version of it. And we believe it is our right. This is what all of this is about," Assed said.

Kazi, also the author of Islamophobia, Race, and Global Politics, told MEE that Emgage's approach to those critical of its efforts was only one of the methods used by the Democratic Party for decades. She says it is with a sense of deja vu that she recalls elections cycles from years past, in which "we were met with desperate pleas that 'this time it is the most important election, so please - set aside your agitation for now'."

"The Democratic party leadership consistently leans right, then shames those who cannot, in good conscience, cast a vote for a party that has not offered a substantive reason to do so.

"In fact, every four years bring the same rejoinders: that this is the most important election ever; let's just vote them in first and then we'll push them to do the right thing; that not voting for a Democrat is a vote for a Republican. People who remember past election cycles recognise such comments as efforts to quell dissent."

Kazi adds that people who remember history "know full well that mass, collective action has done far more to push for social change than have any electoral politics".

"Or perhaps more accurately, the movements force us to recognise the coziness of both parties on the very issues that impact the margins the most: warfare, foreign policy, labour, and criminal justice."

In its American Muslim Poll 2020 report, released on 1 October, the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), said that given that a quarter of Muslims in America are not eligible to vote (because they are not citizens), data suggest that even if 78 percent of Muslims eligible to vote have registered to do, the number of Muslims actually registered to vote in real terms is around 57 percent of the overall community.

"As 1% of the population, with a quarter not eligible to vote, voting in national elections may not be the most effective way to assert political influence," the ISPU said.

"The next generation of organisers may work to encourage greater participation in local political races where Muslims can make a difference with campaign contributions and volunteering, as well as voting."

Likewise, Raja Abdulhaq, from the Majlis Ash-Shura: Islamic Leadership Council of New York, told MEE that the Emgage saga has already had more far-reaching implications than merely November's vote.

Abdulhaq says young Muslims who are increasingly speaking the language of intersectionality and are awake to the connections between racism, police brutality, American militarism and Palestinian rights, are likely to become even more disengaged from the political process.

"They look at organisations like Emgage and see through them. Then they look at the other groups who worked with Emgage and think that instead of being resolute, committed and brave to the causes that matter, they surrendered, too, and became complicit," Abdulhaq says. "Any young person watching all of this play out will think to themselves, 'what the hell is all of this?'

"It actually just takes the community backwards," Abdulhaq said. "This is the tragedy."

Illustration by Mohamad Elasaar/MEE.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].