Russian mercenaries in Libya: 'They sprayed us with bullets'

Esbia, Libya - When the Wagner mercenary placed his hand on Mohammed Abu Ajila Enbis’ shoulder, pushing him into the gravel and cocking his gun, the 28-year-old was scared - but most of all he was surprised.

“They’d treated us well,” he tells Middle East Eye, standing in the bullet hole-ridden outhouse where he lost his father, brother and brother-in-law. “They’d given us food and drink, and we assumed they would eventually just let us go.”

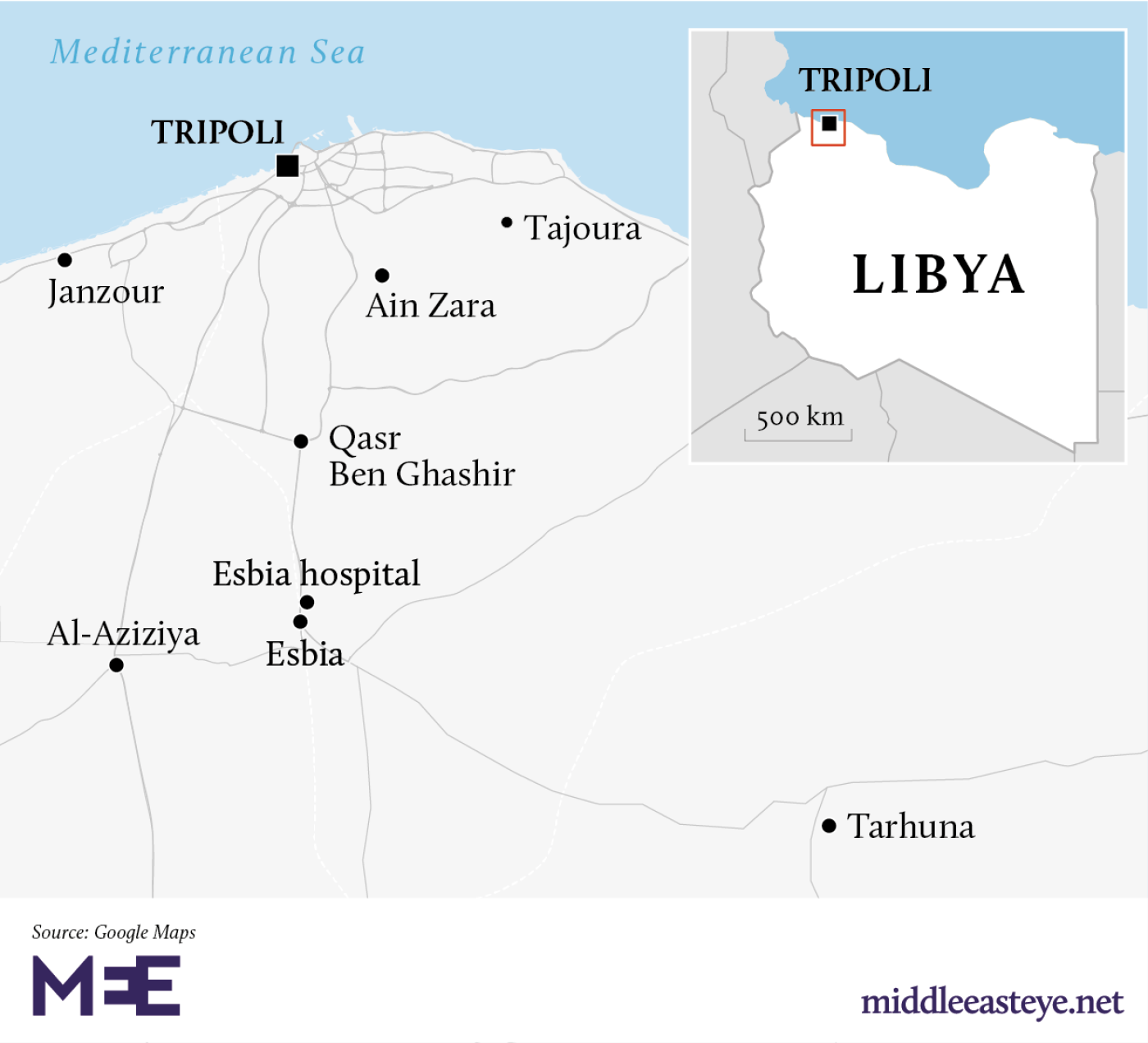

Enbis stumbled across the foreign fighters, speaking what sounded like Russian and English, near his home in Esbia, a rural town 50km outside Tripoli.

He’d been forced from his home by heavy fighting on 23 September 2019, when the assault on Tripoli by eastern commander Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) was at its height.

Now, with a lull in clashes, Enbis had risked heading home to check on his property. But as he crept through the fields, using the long shadows cast by the late afternoon sun as cover, he stumbled across the mercenaries.

They likely belonged to the Wagner Group, a Kremlin-linked private army sent to Libya to prop up the LNA as it struggled to seize Tripoli from the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA).

“They turned around, saw me and fired warning shots in the air,” he recalls. “But then, when I started to flee, they followed me.”

Inadvertently, Enbis led the fighters to the house where he’d been sheltering in nearby al-Hurriyeh. There, they detained him, along with his father Abu Ajila, brothers Hussam and Mohammed, and brother-in-law Hamza.

'Each Russian was big, heavily built, and one seemed to have a prosthetic leg'

- Mohammed Abu Ajila Enbis

“They took our IDs and phones, and they had lots of equipment and were speaking clearly in Russian,” Enbis says.

During the next few hours they moved the family from place to place. “At one point they took us to a field command post, where they seemed to be discussing with their commanders what to do with us,” he says.

“It was a hot night, and while they kept us in the back of a van they doused water over our heads. The water made our blindfolds transparent, and I could see their bright red faces and green eyes. Each Russian was big, heavily built, and one seemed to have a prosthetic leg.”

Eventually, Enbis and his family were taken to a farm. One by one they were walked, bound and blindfolded, into a concrete outhouse, then forced to kneel in a row.

“I was the last to be lined up. Then they sprayed us with bullets. I threw myself down and pretended I was dead.”

But the fighters, apparently in a hurry, left without checking their captives were dead. Enbis lay silently in the dark next to his lifeless and bloody relatives until, after a few minutes, he heard: “Brothers, are you alive? What happened? What happened? Father, are you alive?”

Enbis’ brother Hussam had survived, but had been shot several times in one leg. The rest of the family was dead.

Wagner Group: The Kremlin's proxy army

As a private military company, an opaque amalgamation of shadowy firms and contractors, Wagner has no official links to the Kremlin. But its ties to Yevgeniy Prigozhin, a close associate of Vladimir Putin and former restauranteur, tell a different story.

As do the theatres it operates in: Wagner mercenaries have been reported as active in Syria, Ukraine, Belarus and the Central African Republic, all places of strategic interest for Moscow.

Kirill Semenov, a Libya expert at the Russian International Affairs Council think tank in Moscow, tells MEE: “Wagner independently concludes contracts for its activities. But before concluding a contract, it coordinates with the structures of the Russian government, though I think this is hardly the Kremlin. Most likely, the Wagner leadership is coordinating its actions with the defence ministry.”

Moscow has largely hedged its bets in Libya, eager to secure both $4bn worth of construction and arms deals it signed under deposed dictator Muammar Gaddafi and a foothold in the Mediterranean. As a result, in recent years it has kept lines open with Haftar, the GNA and even Saif al-Islam, Gaddafi’s son.

Yet its support for Haftar has grown over time. A 2016 visit by Haftar to a Russian warship was followed by economic and logistical aid, and eventually a deployment of 300 Wagner fighters in March 2019, a month before the LNA's assault on Tripoli was launched.

As the LNA struggled to break through the capital’s outskirts late last year, Haftar sought more help. Already, he had the military backing of Egypt and the UAE, which supplied him with weapons, equipment and air power, as well the diplomatic cover of France. But he needed extra expertise - and for this he turned to Russia.

Some reports have put the number of Wagner operatives in Libya in the thousands, although Semenov says that number is unlikely unless Syrians recruited from pro-Bashar al-Assad militias are taken into account.

Russians dominate its ranks, but Wagner is also known to employ Serbians and Ukrainians. Meanwhile Enbis’ recollection of the mercenaries speaking English raises the question of other nationalities, too - something Semenov suggests could be attributed to Wagner’s involvement in Ukraine.

“Representatives of many countries, including the EU, fought in Donbass, and could remain in touch with them,” he says.

In Libya, Wagner’s mercenaries provided training for LNA fighters, aided artillery teams, guarded high-ranking officers, operated Russian Pantsir air defence systems and repaired military equipment. The group’s fighters also operated as particularly effective snipers, sowing fear in GNA forces and civilians alike.

But essentially, Wagner's fighters allowed the LNA's battalions to take the lead on the more difficult and dangerous frontline.

“In general, the contribution of the Wagner Group to the stability of the LNA front near Tripoli was quite large. But this is more about defence. Wagner had few resources to support the LNA offensive,” Semenov said.

Undeniable: Russia's involvement

By spring 2020, Moscow’s mood had changed. Wagner had initially given Haftar’s offensive new impetus, but it also prompted Turkey to back its ally the GNA with drones, weapons and Syrian mercenaries.

Sensing that a continued siege on Tripoli was futile, Putin spoke to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on 8 May, precipitating a Wagner withdrawal.

The images subsequently circulated online and in Libyan media were striking: convoys of armoured vehicles charging east, leaving the LNA to fight alone.

Haftar’s forces have long denied the Russians’ presence, despite the odd photo or video clip of well-tooled foreigners on roads or in restaurants. Now this latest footage made those denials all the more toothless.

The LNA quickly began losing ground. As fighters allied to the GNA quickly recaptured Tripoli’s suburbs, more evidence of the Russian involvement was uncovered, including elaborate mines and booby-traps left in homes, a tactic condemned by the US.

The United States’ Africa Command (AFRICOM) said in July it had clear evidence that Wagner planted landmines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in and around Tripoli. “The Wagner Group’s irresponsible tactics are prolonging conflict and are responsible for the needless suffering and the deaths of innocent civilians,” said Major-General Bradford Gering, its director of operations. “Russia has the power to stop them, just not the will.”

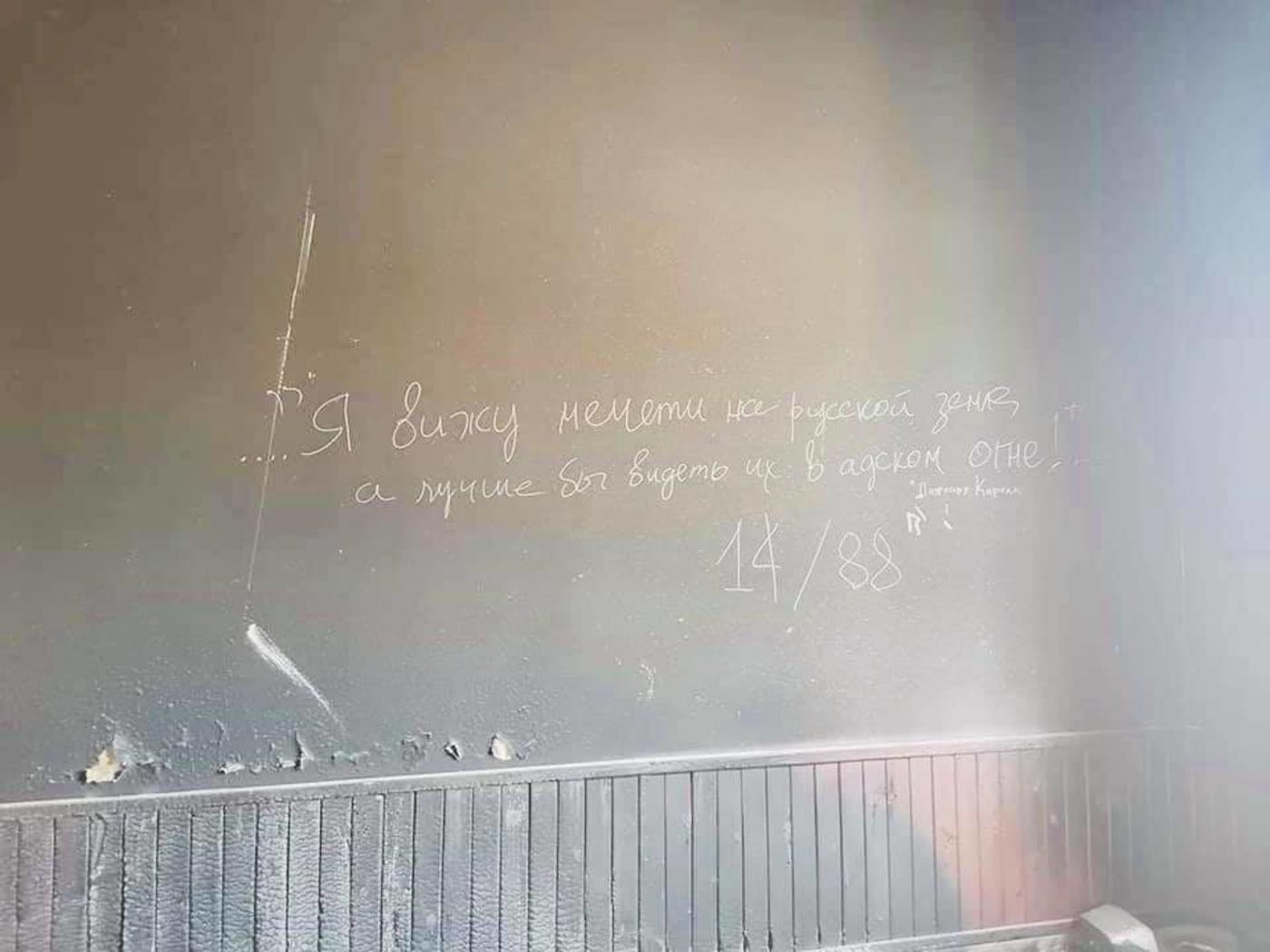

In the suburb of Ain Zara, white nationalist graffiti was found scrawled in Russian on a mosque’s walls.

One line read: “I see mosques on Russian soil, but it would be better to see them in hellfire.” It was accompanied by the 14/88 neo-Nazi tag. Another read: “There is no black in the colours of Zenit,” a nod to the St Petersburg football team, whose ultra supporters are notoriously racist.

Such sentiments are common among Wagner’s ranks, Semenov says. “From what is known, there are indeed a lot of fascists, Nazis and racists in Wagner who identify with the ‘white Vikings’. Moreover, many of them are not Orthodox Christians, but pagans.”

'A booby trap went off and killed him'

Ringed by oval outer walls and dotted with pine trees, Esbia’s hospital made the perfect, and serene, headquarters for Wagner. Surrounded by open land, its fighters had a clear view all around. The complex lay far from the GNA’s artillery range while having quick access to the frontline.

The facility also boasted a water tower, two electricity generators and multiple accommodation suites, thanks to Gaddafi’s propensity to build hospitals with rooms where foreign medical workers could live.

But when the order came to retreat, new temporary positions had to be secured, to the distress of Ahmad Ammar Ahmad, a mechanic in nearby Tarhuna.

On 21 May, Ahmad’s 20-year-old son Amr returned to their Tarhuna home to find the door open and three military vehicles parked in the adjacent workshop. Quickly, he summoned his father.

“I saw Russians using communications equipment. When I tried to negotiate with them, a huge Syrian arrived called Burkan. He said: ‘We’re brothers, don’t worry. We only need this place for a few days and we’ll give it back to you in perfect condition’,” recalls Ahmad.

Not wanting to attract the attention of the LNA’s feared Kaniyat militia who ran the town, Ahmad eventually relented, only returning two days later when Wagner’s antennae had been removed from his roof and the pictures of the mercenaries’ withdrawal flashed up on TV.

The place was a tip. Cigarette butts, shoes, bags and trash were everywhere.

“We started cleaning to get the place ready for Eid. The bathroom was a mess, and we were worried about coronavirus. The water wasn’t running, and when my son started going up the stairs to the roof to check on the water tank, a booby trap went off and killed him.”

Another explosive was found further up the stairs. When Ahmad tried to register his son's death, LNA authorities in Tarhuna bristled at his story.

"They told me 'There are no Russians here, only a Libyan army' and made me say a Turkish air strike killed my son instead."

Haftar's permanent allies

For Russia, private military contractors such as Wagner are a way of getting boots on the ground without getting its hands dirty. The company's murky structure gives Moscow a certain distance and deniability, particularly as atrocities are reported.

On 14 October, however, there was a significant development: Prigozhin was hit by EU sanctions due to his “close links, including financially” with Wagner and its breaches of an UN arms embargo on Libya, which “threaten the country's peace, stability and security".

Hanan Salah, Human Rights Watch’s senior researcher for Libya, calls the sanctions positive, “but it really doesn’t go far enough".

"I don’t think that the European Union should stop there. Are they going to sanction any Turkish groups? Are they going to sanction the United Arab Emirates or Egypt for their violations of the arms embargo?" she tells MEE.

“Don’t just stop at the arms embargo violations but look at the fallout of that, the violations that result in the violation of the arms embargo.”

When MEE asked Major-General Ahmed al-Mismari, the LNA’s spokesman, about Wagner’s involvement in the Tripoli offensive, he said that he had “no idea” what MEE was talking about. “But I know that Russia has great forces and they have positions all over the world, even in Britain and also near the borders of USA. If they want to be somewhere no one can stop them.”

Meanwhile, Tripoli’s relations with Russia are now frosty, to say the least.

Two Prigozhin-linked Russians were arrested in May 2019 while liaising with Saif al-Islam Gaddafi about a possible political comeback, and are now held in a detention centre at Mitiga airport on the outskirts of Tripoli. The body of a Wagner fighter is also held nearby, sources have told MEE.

Meanwhile, Wagner’s troops are fortifying the city of Sirte and al-Jufra air base on the frontline that runs down central Libya. They have also occupied Sharara, the country’s largest oil field.

Russia remains a key player in international attempts at reconciliation talks between Libya’s eastern and western rivals, however, and reportedly supervised a dialogue in Egypt in September.

But that hasn’t dissuaded western Libyan officials from seeking further international action against Wagner, whose fighters now appear to have become a permanent fixture in Haftar’s ranks.

“People should wake up and take notice of the Wagner’s crimes - here and worldwide,” Rabia Abu Ras, an MP based in Tripoli, tells MEE.

“They are like Daesh, a terrorist group. Now they even threaten the world’s oil supplies.”

Photo: Mohammed Abu Ajila Enbis at the home he was displaced from in Esbia in late 2019 (MEE/Daniel Hilton)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].