Why Turkey's plan for a cyber homeland is doomed to fail

“Who are you?” asked a tweet with an accompanying animated video posted last week by the youth branch of Turkey’s governing AKP.

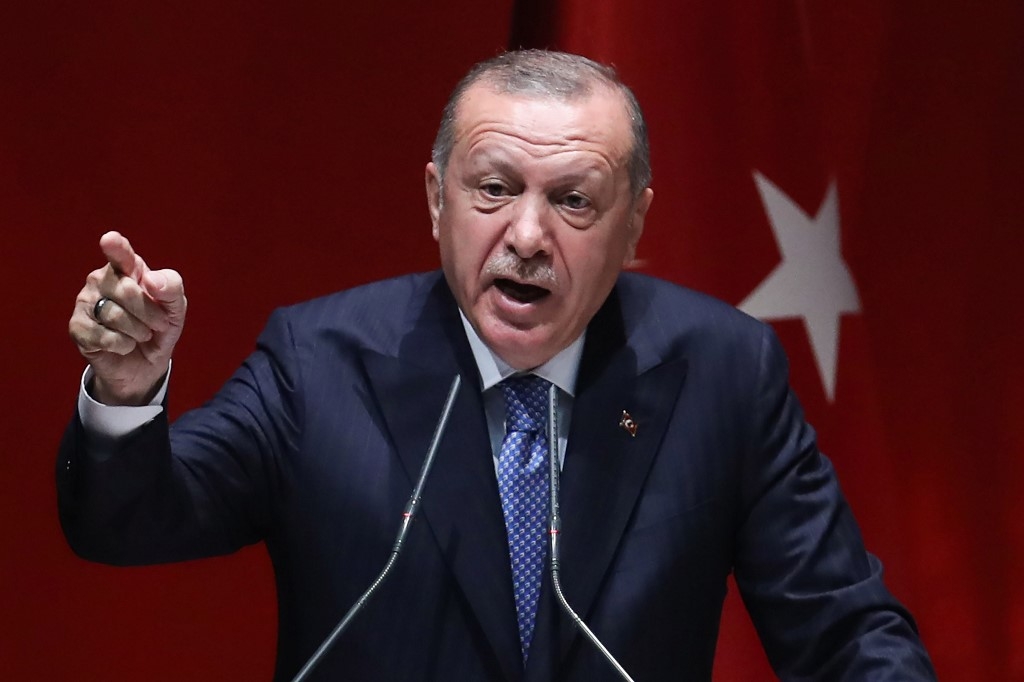

The three-minute video clip begins with a voiceover: “You are young. This is just the beginning for you. You have a lot of work and many concerns, but you are never alone.” It goes on to tell the youth who they are, listing dozens of names, including prominent figures in Islamic history and Ottoman sultans. Without clarifying the nature of these “many concerns” that the youth might have, the clip concludes: “You are Turkey. You are the hope of the ummah. You are [President] Recep Tayyip Erdogan.”

The video clip posted to Twitter was the latest in a recent series of attempts by the ruling party to appeal to the youth as part of its digital transformation strategy

The video immediately stirred a response from young people, but not in the way desired by its creators. They stormed Twitter, with tens of thousands of tweets pointing out what the clip lacks: their concerns and despair. “I’m the one who always fails at job interviews because I don’t have a reference from AKP,” one tweet notes. “I’m a fresh graduate who worked day and night to pass my exams with high scores only to end up being jobless,” reads another.

Three weeks earlier, a new law aimed at regulating social media in Turkey had come into effect. What some Turkish observers might not realise is that the failed AKP youth video and this legislation are very much linked. Both have to do with the ruling party’s growing anxiety over losing the youth vote.

According to the Turkish Statistical Institute, the unemployment rate among Turkish youth is 26 percent, the highest rate in the last 20 years. A recent poll indicates that 79.3 percent of those aged between 15 and 25 believe it’s not how skillful they might be that will help them succeed in their careers - if they get to have one - but rather whether they have an influential figure from the political class backing them.

Being “the hope of the ummah” aside, these youth have lost hope for their own future. More than 60 percent of them, the same poll shows, say that they would like to leave the country if given a chance. Even nearly 50 percent of AKP supporters and around 70 percent of those who support its ally MHP said they would prefer to live abroad.

Cultural colonialism

The video clip posted to Twitter was the latest in a recent series of attempts by the ruling party to appeal to the youth as part of its digital transformation strategy. This strategy has visibly failed, as it addresses none of the actual concerns plaguing youth.

On 26 June, Erdogan went live with high-school students on YouTube. The stream didn’t go well, so much so that the comments section was eventually disabled, as the live broadcast was bombarded with dislikes and hashtags like #OyMoyYok, meaning “you won’t get our vote”.

It’s little wonder, then, that a 79-page report presented to Erdogan earlier this year proposed to create local digital platforms “that protect our data and process it in order to produce content that is in line with our cultural identity”. The report argues that social media giants, which dominate youth culture, pose a challenge for the country and should be regulated. It accuses Silicon Valley tech firms of cultural colonialism and undermining state authority. “Our response should be cyber sovereignty, cyber homeland and digital Turkey,” the report says.

New legislation that the Turkish parliament passed in July, right before its summer recess, has put this strategy into force, leaving no room to discuss objections raised by opposition parties, civil rights organisations and experts.

In effect since 1 October, the legislation aims to strengthen authorities’ control over social media companies and content circulating across their platforms. It requires social platforms with more than a million unique connections per day, such as Google, Facebook and Twitter, to appoint a representative in Turkey, comply with content removal requests and store user data inside Turkey.

A month past implementation, no social media giant has responded to the legislation. Should they refuse to comply, social networks that dominate the Turkish-language internet with 54 million users - two-thirds of the country’s population - will face bandwidth throttling and end up being largely inaccessible by next May.

It's not the medium, it's the message

Turkey is far from the only country that wants to regulate social media content. It certainly has the right to demand that big tech companies follow the country’s rules and norms, as many others do - and as profit-focused enterprises, they are unlikely to give up on the lucrative Turkish market. But what worries many is not the regulation of these platforms per se, but what the ruling party envisions as their replacement.

A cyber homeland strictly controlled by the state, just as the media is, won't help Erdogan's government appeal to the youth

Given the performance of Turkey’s mainstream media, which is in large part under government control, it’s clear how the cyber homeland that the AKP wants to create would look. It would be full of exclusionary religious and nationalistic rhetoric, and largely intolerant of criticism or alternative voices. According to a report released by the Istanbul-based Freedom of Expression Association, the number of websites blocked in Turkey had risen to 408,494 by the end of 2019, up from 80,553 just four years earlier.

Speaking at the opening ceremonies for a university complex last week, Erdogan criticised the media for falling short of his expectations. “Although equipped with all the cutting-edge infrastructure, our media doesn’t reflect our voice and soul,” he said.

Yet, his government’s digital transformation strategy offers no new direction - just more of the same, and thus it is doomed to fail. A cyber homeland strictly controlled by the state, just as the media is, won’t help Erdogan’s government appeal to the youth, because what it lacks is not the medium - it’s the message.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].