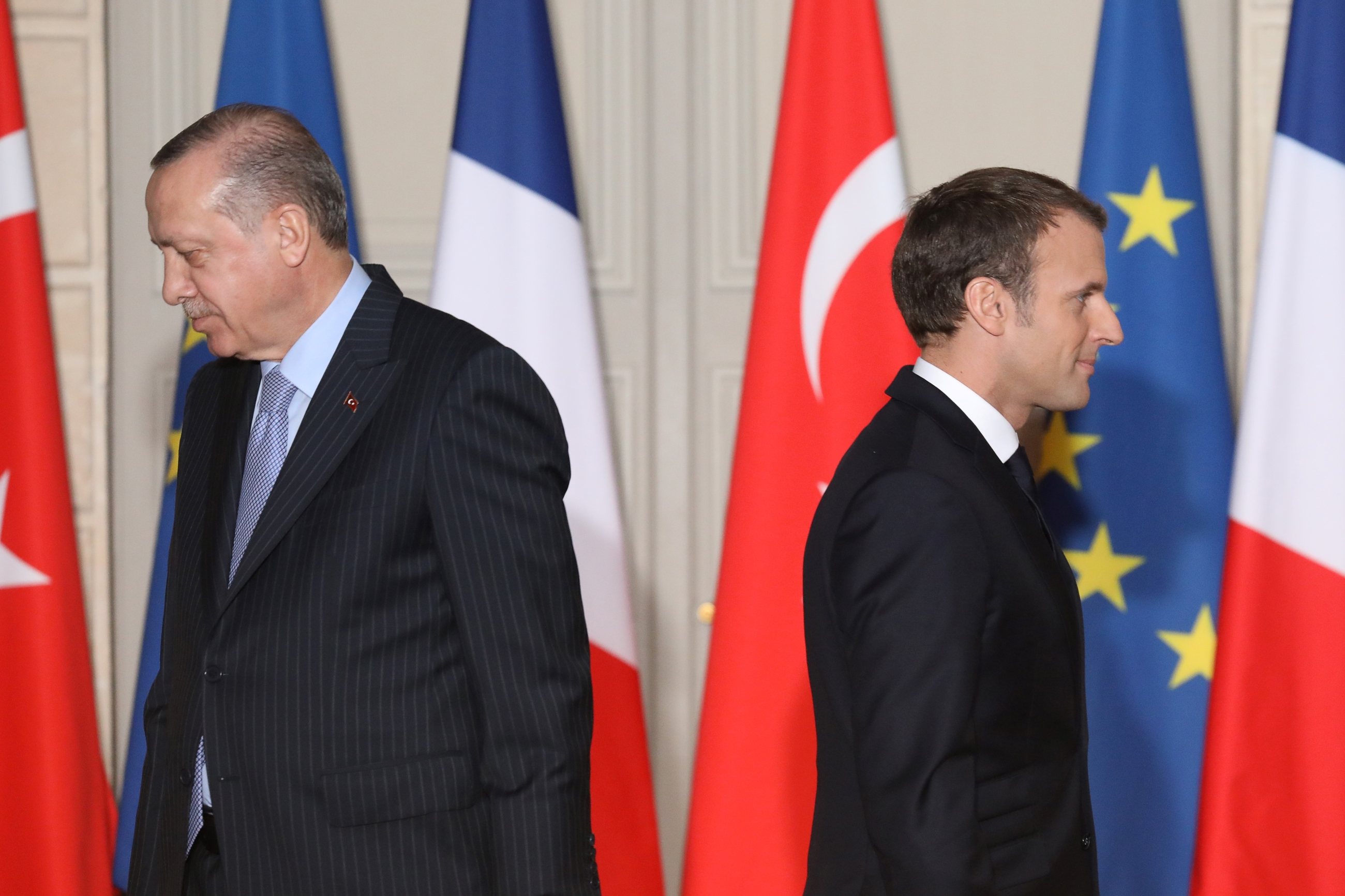

France-Turkey showdown: A battle to shape the regional order

The rapid deterioration in relations between France and Turkey has recently seen President Recep Tayyip Erdogan call for a boycott of French goods over President Emmanuel Macron’s defence of the display of cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad.

Prior to the most recent diplomatic spat, the two Nato members faced each other in a standoff in the Mediterranean.

After Turkey deployed naval vessels to accompany its seismic research ship seeking hydrocarbon resources in the Eastern Mediterranean, France accused it of violating Greek and Cypriot waters, calling for EU sanctions. Ankara initially refused to pull out and threatened retaliation against any nation that would attack its ships, while Paris deployed jets and warships to deter Ankara, while arming Greece through generous (and very opportunistic) weapons sales.

Because its own claims and needs have been disregarded by the international community... Turkey has been forced to try to strike its own bilateral agreements

Before the recent escalation, tensions had eased. Turkey withdrew its exploration ships in mid-September, the EU declined to pass sanctions against Turkey, and Greece and Turkey announced a “military deconfliction mechanism” to avoid accidental clashes at sea.

Turkey remained on notice and under threat of future sanctions should it persist in its “aggressive” behaviour and “unilateralist” enterprises. Despite that sword of Damocles, Erdogan announced in mid-October that he was sending an exploration vessel back to resume the search in the Mediterranean, defying EU threats.

Turkey’s search for energy resources in this part of the Mediterranean has predictably been presented by French media and President Macron himself as “inadmissible behaviour” and “provocations” on the part of a rogue leader - which has by now become routine treatment for everything Erdogan does or says.

In France, Erdogan-bashing has become a national sport, and an outlet through which a deeply Islamophobic society (its government elites included) self-righteously expresses fear and detestation of Islam and Muslims under the alibi of “fighting Islamism,” which is wrongly equated with “jihadist” terrorism (seen in deadly attacks outside a church in Nice and the killing of a French teacher).

Yet, contrary to what is being suggested, Turkey is not violating international law; it never signed the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, by which signatory states can claim a 200-nautical-mile area as their exclusive economic zone (EEZ) to exploit the resources contained therein. Such international conventions cannot be forced on states that never signed them.

Fierce competition

Given that gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean are estimated at 3.5 trillion cubic meters (large enough to power the US for a decade), the region has become the object of overlapping claims and fierce competition to secure energy rights for the rest of the century, with each country understandably wanting a piece of the pie.

Turkey - which imports more than 90 percent of its oil and natural gas, and has a growing population and economy - has been eager, like all nations, to secure much-needed natural resources. Yet, it has largely been excluded from the intense rounds of multilateral and bilateral diplomatic negotiations, and the resulting deals and agreements (in particular among Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, Italy, Lebanon and Israel), which are carving up those resources right under Turkey’s nose.

Because its own claims and needs have been disregarded by the international community, and in particular by the EU and regional Mediterranean states, Turkey has been forced to try to strike its own bilateral agreements, so far with only minimal success - most notably with Libya - while using its own definition of its EEZ.

Amid competing claims and counter-claims, and contested delineations of maritime zones that often overlap each other (as with the Turkish-Libyan corridor, parts of which are located on Greek and Cypriot EEZs), these nations are now accusing each other of violations of rights and sovereignty.

Despite its great isolation, with only the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) and northern Cyprus on its side, Turkey’s grievances, needs and claims are perfectly legitimate, and the international community should recognise them as valid. But there is little chance this will happen.

Worsening animosity

Most notably, the Greek claim that all of its myriad Aegean islands must be entitled to the same exclusive perimeter and maritime jurisdiction as Greece’s mainland is an aberration. As Greece possesses hundreds of islands, many of which sit just off the Turkish coast, this means that Turkey would be stripped of maritime rights, boxed in on its continental shelf.

Only a new round of diplomatic negotiations, potentially at the International Court of Justice, on the status of the Aegean Sea - one that would include Turkey and recognise the legitimacy of its claims and needs - could stop these escalating crises in the Mediterranean.

Even before the latest disputes, the ever-worsening animosity between Erdogan and the last three French presidents resulted from a years-long accumulation of contention and policy divergence. This has involved rival political and geostrategic ambitions in the MENA region, but increasingly in Europe as well, as illustrated recently by Turkey’s intervention in the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict.

The growing list of grievances include the Syrian war, where Turkish forces attacked Kurdish combatants who sided with the West against the Islamic State; the Libyan conflict, where France supports warlord Khalifa Haftar and Turkey backs the internationally recognised government; the refugee crisis, which Erdogan has instrumentalised as a bargaining chip with Europe; and Turkey’s purchase from Russia of sophisticated weapons systems, fuelling accusations that it is betraying its Nato allies.

Other issues include Turkey’s conversion of the Hagia Sophia back into a mosque, criticised all over Europe and beyond as (what else?) a “provocation”; and Erdogan’s alleged “interference” in France’s affairs, with the Turkish president regularly accused of trying to use the Turkish diaspora to “export his own brand of Turkish Islam”.

'Islamist' menace

Each time, without nuance or a second of self-examination, Erdogan is cast as an “aggressor” representing an “Islamist” menace to world peace. But nowhere better than in the Libya conflict can Macron’s hypocrisy be observed, as he blames Erdogan for “interfering” in Libya while apparently taking for granted the legitimacy of his own interventionism.

Two other crucial moments help to explain Erdogan’s growing impatience with what he sees as France’s bullying behaviour. The first is the sabotage by former French president Nicolas Sarkozy of Turkey’s bid for EU membership, a prospect in which Turks and Erdogan himself had enormously invested.

That night, a lot of things changed with respect to Erdogan's understanding of his 'Nato allies' and EU 'partners'

The rejection of Turkey as a possible EU member became a major theme of Sarkozy’s successful 2007 campaign, one saturated with Islamophobic undertones. Turkey’s hopes were effectively killed for good in 2011, when Sarkozy forcefully reasserted his determined opposition to Turkey’s membership. This was long before Erdogan’s “autocratic turn,” which started only in 2013 (the Gezi Park protests were key).

The second moment was the July 2016 coup attempt. That crucial night, Erdogan was able to observe the complete, and complicit, passivity of his alleged Nato partners, including France - none of whom lifted a finger to help Turkey’s legitimate government and democracy, but rather made vague statements about restoring calm. That night, a lot of things changed with respect to Erdogan’s understanding of his “Nato allies” and EU “partners”.

Rival ambitions

The current France-Turkey showdown is also part of competing attempts to restructure the regional order in the short-to-medium term.

For a long time, France has wanted to turn the EU into a major force in the Mediterranean, or at least put an end to its dramatic loss of influence and power. Macron now appears to believe that the time has come for the EU, led by France, to step in and seize the historic window of opportunity opened by the retreat of the traditional “world cop” - the US - from that region.

But Macron’s project to restore France’s historical role as a major power in the Mediterranean and Arab world conflicts with Turkey’s expansionism (including in Africa, France’s backyard), and its transformation from using soft power to, increasingly, hard power.

Yet, these rival ambitions largely cancel out, or at the very least contain, each other. Neither France nor Turkey has the means to realise their ambitions, and both are largely isolated in their respective hegemonic expansionism.

Macron’s repeated efforts to push his EU allies into presenting a unified front against Erdogan have gained little traction. In addition, the US will likely return to the region after the near-certain victory of Democratic candidate Joe Biden in next week’s election.

France and Turkey have been intensely involved in restructuring the regional order around two rival coalitions: one bringing together Turkey, Libya’s GNA and Qatar, and the other - far more powerful - comprising Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Egypt, Israel and the US, backed by France.

The success of the second hegemonic axis, dominated by the most brutal and repressive regimes in the region, would end hopes for democracy and popular self-determination across the region. It would durably seal the fate of Palestine, too - which seems to be one of its long-term goals.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].