More than ever, the struggle for justice unites the Middle East and the world

“A spectre is haunting Europe...” This is how Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels opened their Communist Manifesto, written on the eve of several uprisings on the continent in 1848. The results of the uprisings were a mixed bag; limited success was overwhelmed by reaction and suppression so intense that Marx proclaimed the close of the revolutionary window. The European Spring had come to an end.

More than a century and a half later came the Arab Spring. Starting in 2010, it made its way through Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria and Yemen. Uprisings and revolutions in those countries were accompanied by protest movements in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Jordan and elsewhere.

The results were also a mixed bag: Tunisia, the only successful example, continues to face economic hardships. Egypt’s revolution succumbed to opportunism and then counter-revolution. Interventions in Libya, Syria and Yemen saw their revolutions devolve into protracted civil wars. Protest movements elsewhere where smothered by military repression.

Spectre of revolution

It would have been hard to claim, at that time, that the Arab Spring was not over. But the spectre of revolution proved that it was not done with the region. In December 2018, another string of uprisings and revolutions began to unfold in Sudan, Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon and Iran - and they are far from over, despite being hit by a pandemic.

These two waves were separated by close to a decade, allowing for lessons to be learned from the first. It is best to view them as part of a continuing revolutionary process throughout the region - one that, with the inability of ruling classes to resolve the political and economic contradictions that gave rise to these movements, is bound to evolve and continue.

Studying the uprisings can reveal lessons for those who wish to push forward with a project of political and economic change

Our new book "A Region in Revolt: Mapping the Recent Uprisings in North Africa and West Asia" explains that the uprisings can reveal lessons for those who wish to push forward with a project of political and economic change, and to help secure an outcome better than the mixed bag we have seen so far. Although each country in the second wave of uprisings presents unique historical experiences that helped to determine the social forces engaged in struggle, it is the methods and tools of struggle that are the most transferable.

Sudan’s uprising presents the greatest potential for revolutionary instruction. It began as a series of protests against rising prices of basic goods, especially bread. Localised protests quickly transformed into nationwide ones, and a rallying cry of “just fall” gained prominence.

Although the Sudanese people were rising up against a specific ruler, they were also trying to break a cycle of rotation between “democracy” and military dictatorship, which has haunted the country since its independence from Britain in 1956.

Sudanese call for change

What makes Sudan unique is the structure that evolved throughout the uprising. A banned union, the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), founded in 2012, took a leading role, releasing weekly protest schedules and march routes. Understanding that they alone could not impact change, they reached out to various opposition parties, and were able to form a coalition known as the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC).

Twenty-two parties and groups signed the declaration that forged the coalition, representing a broad range of political opinions. All agreed on the need for change.

As important as the FFC was the role played by resistance committees. These grassroots neighbourhood groups helped organise marches and sit-ins, maintaining pressure on the government and on the FFC after they agreed to a deal with the military on shared government responsibilities during a transitional period.

One lesson from Sudan has been the importance of trade unions, which also proved to be indispensable during the Tunisian revolution. This, though, has overshadowed the role of the resistance committees, and the groundwork and networks the SPA built, even under conditions of illegality. This shows that the foundations of any uprising must be long in the making and combine national and local bodies.

Algerian protests merge

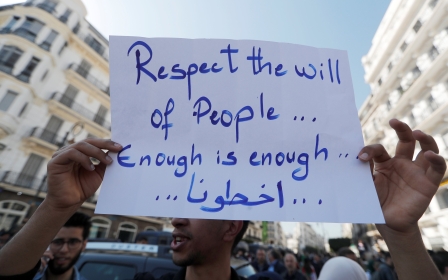

As the Sudanese revolution continued in early 2019, Algerians also took to the streets after President Abdelaziz Bouteflika announced his intention to run for a fifth term. By then, Bouteflika had ruled Algeria for two decades. The protests that erupted maintained a strict discipline, taking place every Friday - and it was this discipline that successfully deposed Bouteflika. In his place, a sham president was installed by the military.

Building on a long culture of anti-imperialist resistance, the Algerian protest movement merged and aimed to solve issues of cultural identity, ecological degradation and economic independence all at once. A strict “Arab” identity imposed by the brutal and violent authoritarian regime was replaced by one that included the Imazighen (formerly known as Berbers), whose flag was flown during protests in contravention of the law.

Regions in southern Algeria, long dismissed due to anti-Black racism, gained prominence through their struggle to prevent fracking plans. This merged with the greater struggle for economic independence from foreign multinational corporations who have been exploiting Algeria’s shale resources since independence.

The inability of the Algerian people to put forward leaders has been identified as a weakness, but the uprising there shows the inseparability of issues, even in a culturally pluralistic nation.

Iran, Iraq and Lebanon

The conditions of Iraq and Lebanon are extremely different, but they share certain challenges. The peoples of both countries have found themselves in the hands of a consortium of sectarian leaders who, on the surface, are at odds with each other - but who will unite as soon as the system that ensures their mutual benefit is threatened.

The Iraqi people have shown heroic resilience in the face of suppression by sectarian militias. In Lebanon, people are fighting against the concept of resilience, abandoning the country’s myth as the phoenix. There is no more pride in rebuilding; now is the time to end the losses.

Both uprisings have identified that the source of their woes is not one sect or another - a long-proven strategy used to keep people divided, especially the working classes. Instead, the enemy has been identified as the ruling classes in their entirety, the web of clientelist relations that sustain them, and the merged public and private economic domains that are reinforced by their hold on power. For a successful transfer of power, it is not enough to attack politicians in state institutions; it is necessary to contest the myths upon which these institutions were built.

In the case of Iran, its imperialist regional role eclipses the genuine and progressive resistance building within it - resistance that is usually met with the most brutal suppression. Similar to Algeria and Sudan, the recent uprising in Iran was triggered by the removal of state subsidies - in Iran’s case, for fuel.

The uprising also took place during heightened tensions between Iran and the US. The assassination of Qassem Soleimani and the subsequent accidental downing of a Ukrainian airliner during reprisal attacks put Iran’s regional imperialism centre stage. Protesters took to the street with chants of “the enemy is at home”, showing solidarity with the uprisings in Lebanon and Iraq.

False dichotomy

The inclusion of Iran in the latest series of uprisings helps to break through the false dichotomy presented in regional geopolitics and by socialists around the world. The choice in the region is not limited to Saudi or Iranian hegemony, nor does solidarity with the uprisings need to be restricted on the basis of archaic, Cold War-era definitions of anti-imperialism - a mistake for which Iranian socialists have paid dearly.

We must be able to identify with genuine struggle within nations, and lend our support while realising the inseparability of our struggles.

This question of solidarity is not limited to our region, in a year where Black Lives Matter protests erupted around the world, alongside worldwide anti-neoliberal protests

This question of solidarity is not limited to our region, in a year where Black Lives Matter protests erupted around the world, alongside worldwide anti-neoliberal protests, from Ecuador to Hong Kong. This all comes as we collectively cope with a pandemic that is creating greater economic and political pressures.

We would all do well to recognise that the suffering of a people in one corner of the earth is the suffering of all, especially considering the impending climate crisis that we are all facing.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].