Al-Qaeda's Maghreb branch has revealed its weakness with new leadership

The death of its leader is a severe blow to any militant group. But in succession, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) may have revealed its true weakness.

In a video posted online on 21 November, AQIM confirmed senior Algerian commander Abu Ubayda Yusuf al-Annabi would take leadership following the death of Abdelmalek Droukdel, who was killed in June by a French-led operation in Mali.

Annabi's lack of operational and combat experience, compared with Droudkel, who rose to the head of AQIM in 2004 as an experienced battalion leader, has led observers to believe he may struggle to deal with the militant group's problems.

Chief among them is its weakening regional dominance, as AQIM suffers from a decline in influence in the face of competition between militant groups in the volatile Sahel region.

Formed in 2007 from militant groups that emerged from the 1990s civil war in Algeria, AQIM has staged several deadly attacks in the Sahel since 2012.

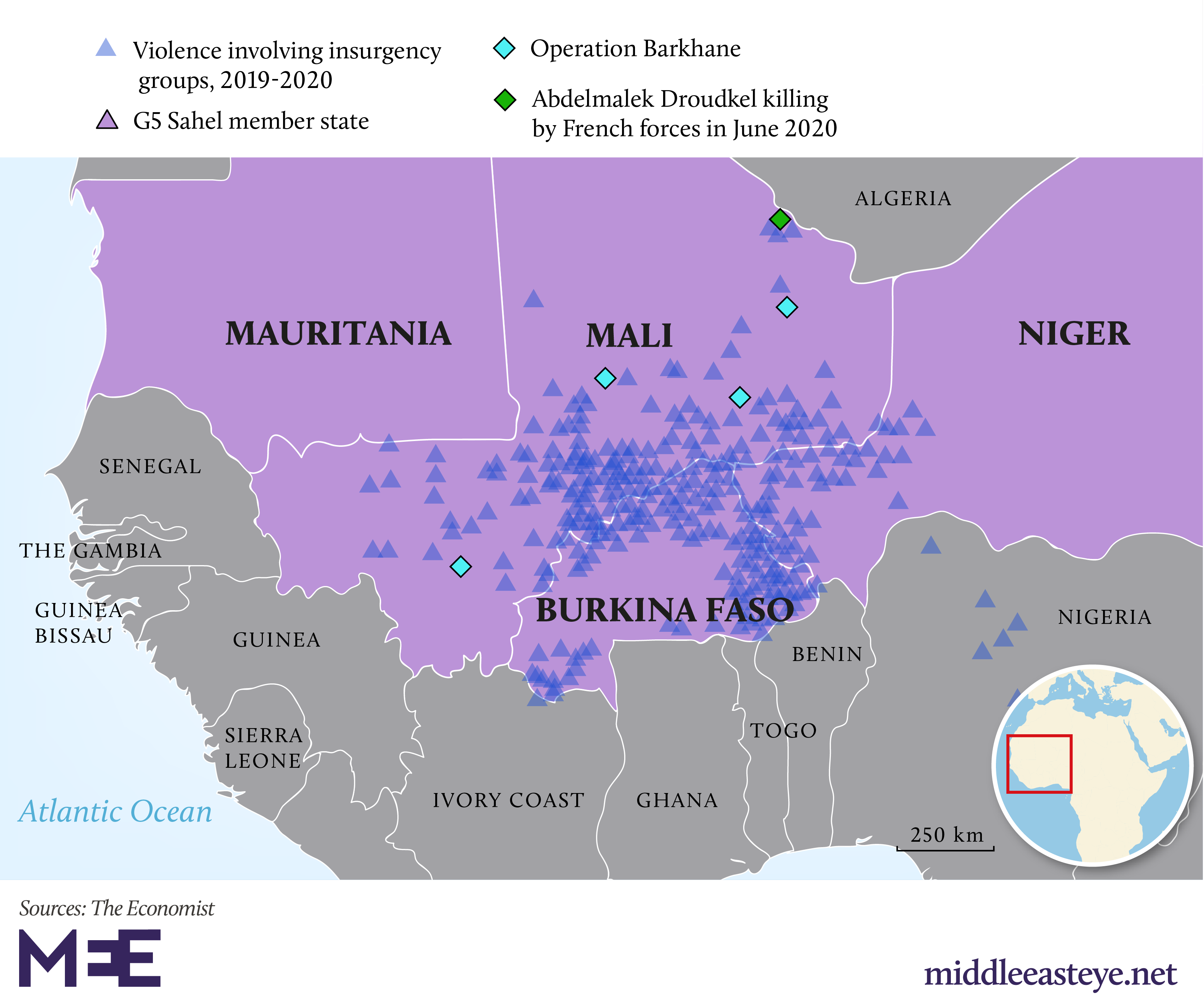

In response, France has deployed over 5,000 troops as part of its Barkhane force, working with the G5 Sahel states of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger to rid the region of the militants.

The conflict has taken 6,500 lives, and among other issues like food security has spurred 2.7 million people to flee their homes. It has also encouraged the rise of several groups competing with AQIM for influence, which often draw fighters along tribal lines.

“The AQIM threat is becoming marginal, the group is struggling for survival," Akram Kharief, Algerian security expert, tells Middle East Eye.

Annabi's ascent

Born in the eastern Algerian city of Annaba in 1969, Annabi, 50, became a militant at the start of the civil war in 1992 after finishing his degree in economics at around the same time as Droudkel.

Since 2010, Annabi has headed AQIM’s “Council of Notables”, which has been led by two previous AQIM leaders, including Droudkel. The Algerian has appeared several times in the group’s propaganda videos (for example urging Muslims in 2013 to retaliate against France’s intervention in Mali) causing him to be blacklisted by the US in 2015 and by the UN in 2016.

The self-styled cleric is likely to prioritise unity between militant movements in the Sahel region.

To offset the presence of its greatest rival, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), which has siphoned off AQIM’s pool of potential recruits and is in “open war” with the group, Annabi is likely to ensure his militants are better rooted in local dynamics, particularly in northern Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger.

That looks like a tall order.

“Annabi, at least from what is publicly known, lacks the resume of any previous AQIM emir, particularly in the operational domain," Alexander Thurston, assistant professor of political science at the University of Cincinnati, told MEE.

'Annabi's appointment may not be sufficient to reverse what seems like AQIM's gradual decline'

- Alexander Thurston, analyst

“His appointment may not be sufficient to reverse what seems like AQIM's gradual decline.”

Amid the growing influence of offshoots, like al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Mali and West Africa, the Group for Supporting Islam and Muslims (JNIM), and the shift of militant activities to the Sahara and Sahel region, AQIM's desire for dominance in local dynamics isn't likely to be aided by maintaining its traditional Algerian leadership, which risks reducing its influence throughout the Sahel further.

“The terrorist organisation has scarce human resources in Algeria and is unable to recruit. The actual strategy is to maintain surveillance in rural areas and in the Sahara,” Kharief says.

Competition between militant groups

According to Hannah Armstrong, a senior consulting analyst with Crisis Group, the militant insurgency of northern Mali and French intervention has transformed militant activity in the region since 2013.

“Instead of being defeated, the militants went underground and resurfaced as rural insurgencies,” she told MEE.

Clashes in central Mali and on the border with Burkina Faso between militant groups linked to Al-Qaeda and those loyal to the Islamic State have defined the presence of the insurgency in the Sahel over the last few years.

Both JNIM and ISGC have been the main focus of recent French-led combat operations, particularly in northern parts of Burkina Faso and in north-central Mali.

In comparison, AQIM are more of an afterthought.

'There has been a stronger push by Sahelian states and their external partners to defeat these jihadist militants but in many cases military pushes into precarious rural border zones have actually led to more violence'

- Hannah Armstrong, analyst

Thurston told MEE: “AQIM had extraordinary success in the early 2010s in terms of raising money through kidnappings for ransom and in terms of its overt participation in controlling northern Mali during the latter phase of the 2012 crisis."

However due to the ongoing military pressure, militant groups are finding it more difficult to launch the type of large-scale attacks on military bases that marked the end of 2019, and are becoming more reliant on recruiting fighters and supporters from local ethnic groups as opposed to cross-border strategies.

As a result, greater prominence has been gained by groups like JNIM through the leadership of local figures.

“In many ways JNIM has eclipsed AQIM,” Thurston said. “Northern Algerian AQIM leaders, including Annabi, have a kind of rhetorical influence and may exercise some operational influence over JNIM.

"But JNIM's Malian leaders also have their own priorities that appear to be rooted in local politics, rather than in dictates coming from Annabi or his predecessors.”

Though seen as important symbolic victories, operations targeting the leaders of militant groups often fail to reduce the overall influence and operational capacities of groups in general.

For their survival, rather than relying on the charisma of its leaders, militant groups exert influence by manipulating domestic grievances and using anger during popular uprisings to act as an authority in lieu of the state.

The impact of Droukdel's assassination remains to be seen. But either way, corruption, limited state resources and state security forces' abuses has made it difficult to break the cycle of violence for Sahel states.

Armstrong told MEE: “There has been a stronger push by Sahelian states and their external partners to defeat these jihadist militants but, in many cases, military pushes into precarious rural border zones have actually led to more violence and higher recruitment levels from JNIM and IS instead of calming things down.

“The trend has really been to throw more military operations at the problem and I think that is relatively unsustainable heading into the Covid era where GDPs of countries are being squeezed. We should see more of an emphasis on political settlements,” he added.

Algeria weighs in

On a state level, AQIM's greatest threat may be the country it singled out as its primary enemy. As the organisation continued to expand its operations elsewhere in the Sahel, it has been struggling in Algeria since 2010.

“AQIM's original target, the Algerian state, no longer appears threatened by AQIM or by jihadists generally. AQIM also appears to have little ability to recruit or even stage major attacks in Algeria, especially in northern Algeria,” Thurston told MEE.

2018 was the first year in more than two decades that Algeria reported no terrorist bombings, and despite the organisation's regular communiques urging action, AQIM has not conducted a significant attack in Algeria since targeting the Krechba gas facility at In Salah in March 2016.

With more coherent counter-terrorism policies and coordination of the Department of Intelligence and Security and the Directorate General for National Security, Algeria has managed to control militant activities of groups like AQIM, which has conducted 600 attacks in Algeria since 2006, and IS-affiliated Jund al-Khilafah, within and along its borders, where it has deployed long-range surveillance optronics.

'AQIM's original target, the Algerian state, no longer appears threatened by AQIM or by jihadists generally'

- Alexander Thurston, analyst

However, despite its counterinsurgency experience, Algiers has failed to dominate proceedings when it comes to dealing with the Sahel conflict and in directing how operations are conducted near its borders, despite its intelligence leading to the capture and killing of a number of militants including Droudkel.

According to Kharief, “France has denied leadership on anti-terrorism in the Sahel mainly because of a lack of trust. They haven’t involved Algeria in the G5 Sahel nor used the Joint Military Staff Committee of the Sahel Region based in Algeria to tackle jihadism in the Sahel."

Algeria's dissatisfaction was heightened last month when French charity worker Sophie Petronin, held since 2016, was freed after being exchanged for over 100 mostly AQIM-linked militants, which prompted Algiers to release a statement deploring “the payment of a large ransom for the benefit of terrorist groups".

A few weeks later, a number of those released were arrested by the Algerian army after they were intercepted at its borders.

Algiers' preoccupation with the security situation in Libya, ongoing domestic issues since Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s presidency and the onset of the Hirak protest movement in 2019 has prevented the Sahel from being its top priority.

Andrew Lebovich, a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, told MEE: "The Algerian government at different times has placed more or less emphasis publicly on the peace process. For instance after Ramtane Lamamra was removed as foreign minister [in 2019], Abdelkader Messahel for a certain amount of time was really more focused on Libya than Mali.”

As Algeria looks to relaunch its diplomatic credibility and to direct some of its focus away from Libya, it is likely to push for a more dominating role in solving the conflict, aside from its repeated calls for the 2015 peace accords, signed in Algiers, be respected.

The recently proposed constitutional changes on the role of the Algerian military, which could see it deployed outside Algeria's borders for the first time, may spell a change in Algeria’s foreign policy principles and how it responds to security threats in future.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].