Iran issues first ID cards to children born to foreign fathers

Last month, the first ID cards for children with Iranian mothers and foreign fathers were issued in Iran, paving the way for the long overdue implementation of equal rights for such children.

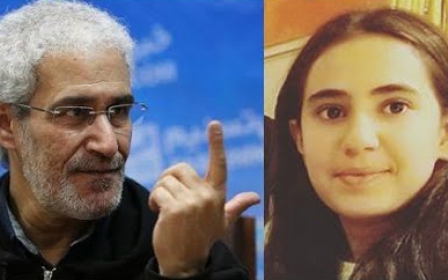

The mother of Rayhaneh, a 12-year-old girl who was one of those who received an ID card in November, told Middle East Eye it was something she had been dreaming about for the past 10 years.

Rayhaneh's Iraqi father was sent by Iran to Syria to fight against Islamic State (IS) and was "martyred" there.

He was one of the young men, many from overseas, who were told they were being sent to carry out their Islamic duty and protect the shrine of the granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad in Damascus.

After a quick visit to the shrine of Zaynab bint Ali, the men were immediately put on patrol in the capital or sent off to the front lines, where they were told they would be fighting IS.

Of those who survived, many have spent years waiting for promised Iranian visas that never materialised.

Rayhaneh's mother, an Iranian from the southwestern city of Ahvaz, is jubilant at seeing her child enjoying the rights she had until now been denied.

About 75,000 people have applied for the ID cards since the passage of the new citizenship law in May, which came into force only recently.

About 75,000 people have applied for the ID cards since the passage of the new citizenship law in May, which came into force only recently.

Prior to the new law, Iran only accepted the immediate inheritance of citizenship from the father, with the citizenship of children born to Iranian women married to non-Iranians possible only after the age of 18, and on certain conditions.

Deprived of an education

The issue of granting citizenship to the children of Iranian mothers and foreign fathers was first discussed in the Iranian parliament as far back as 2006.

The original plan included allowing children to apply for citizenship, but opposition led to the passage of a single article postponing citizenship applications until the age of 18.

As a result, children of non-Iranian fathers and under the age of 18 were left without ID cards and consequently deprived of many primary rights, including the opportunity to study at school.

According to Masoumeh Ebtekar, Iran's vice president for women's affairs, the number of such children ranges from 50,000 to 200,000.

Ebtekar told newspaper Iran that the majority of the children, who mostly have Afghan or Iraqi fathers, live in border areas and provinces such as the northeastern Sistan and Baluchestan.

She said that two years ago she visited Sistan and Baluchestan to open a school in Iranshahr.

"The school was for girls who didn't have a birth certificate and had dropped out of school," said Ebtekar.

"There I met 12-year-old and 14-year-old girls who couldn't read or write [as they had not been able to attend school] due to not having birth certificates."

'Did I commit a sin by marrying a good Afghan man?'

Mahsa, an Iranian woman married to an Afghan man 20 years ago, told MEE of her family's struggles. "I currently work in a tailoring company, and my husband is at home taking care of my children, as he can't find a permanent job due to his nationality," she said.

"The worst thing is that my three children have not been able to obtain ID cards, which has caused them to go through various troubles. Did I commit a sin by marrying a good Afghan man?"

Speaking of her own hardship, Roghaye, whose father is Afghan, told MEE: "I couldn't even get a SIM card like my other friends, and this was a clear and meaningless discrimination.

"I could also not work anywhere, due to the lack of an Iranian ID card.

"Once I worked in a pharmacy, but while my employer was satisfied with me – trying to turn my job status into a permanent one, and to add me to the list of pension recipients – he finally couldn't make it work, as I didn't have any nationality."

In 2015, a new bill for granting citizenship to the children of Iranian mothers was raised in parliament, but was again rejected by the majority of MPs. Opponents argued that giving citizenship to the children of Iranian mothers could result in the growth of immigration to Iran.

Security threat

Three years ago, following the death of the celebrated Iranian mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, who was awarded a Fields Medal in 2014, the need to change the citizenship law once again came to the attention of the media and activists.

At the time, it was reported that Mirzakhani's daughter was unable to obtain an Iranian passport as her father was from the Czech Republic.

Sixty Iranian MPs urged the speeding up of an amendment to the law in order to make it easier for Mirzakhani's daughter to visit Iran.

In 2019, a new bill was finally passed by Iran's parliament to grant citizenship to children through the mother.

However, the bill faced obstacles after the Guardian Council – which will only approve bills if they are in accordance with the constitution and Islamic law – argued that possible security threats arising from the approval of some applicants had been ignored.

Eventually, after the disagreements between parliament and the Guardian Council were finally resolved, the law was sent to President Hassan Rouhani for him to declare its enforcement.

However, it took Iran's executive bodies several months to finalise the regulations, leading to implementation of the law in May, and it was another six months before the first ID cards were issued.

Opening doors

"This year was one of the best years of my life, despite all the bad things that happened to my country and the world, including the coronavirus pandemic," Heliya, 17, who has an Afghan father and is one of those who has applied for an Iranian ID card, told MEE.

"I can now see many of my dreams fulfilled, things which may have been quite simple for others."

Heliya spoke of how the lack of an Iranian ID had prevented her from exploring her passions.

"When I turned 15, I was very interested in Wushu [a Chinese martial art]. I went to register in one of the clubs," she said. "The first thing they told me was to bring a copy of my ID card and an amount of money for registration. I did not like to say 'My mother is Iranian but I do not have an Iranian identity card,' so I never went there again. I can now go there to apply."

Amanollah Qara'i Moqaddam, a sociologist and professor at the University of Shahid Beheshti in Tehran, welcomed the enforcement of the new citizenship law.

Qara'i Moqaddam told MEE he thought a person without any nationality could easily be exposed to all kinds of crimes, as they could feel socially rejected and look for an opportunity to take revenge on those around them.

He said that not only did the new law have a highly positive effect in terms of human rights, but that it could help allay a shortage of workers in coming years, as the offspring of transnational marriages could help increase the active element of Iran's ageing population.

According to Iran's semi-official ISNA news agency, a quarter of the country's population will be considered elderly by 2050, as the population growth rate continues to decline.

But for some, the law means their identity will finally feel validated.

Hassan, 23, told MEE how the relatives of both his Afghan father and Iranian mother did not consider him as belonging to either Afghanistan or Iran.

"No one has understood me during all these years and how I felt about these things," he said. "But now I'm happy, because once my ID card is issued and I get Iranian citizenship, at least my relatives' views will change."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].