Why Turkey returned to the Caucasus after a hundred years

It took 44 days for Azerbaijan to defeat Armenian forces in Nagorno-Karabakh and make Turkey one of the fundamental players in the Caucasus.

And today, Turkey's power in the region could not be clearer.

Words thanking Ankara were some of the first from Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev's lips when he joyously declared a ceasefire on TV last month.

In response, people flocked to the streets with Turkish and Azerbaijani flags, bellowing chants praising Ankara.

Two days later, some of the leading members of Azerbaijan's opposition addressed an open letter to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, ignoring Aliyev. They called on Turkey to deploy permanent troops to the Nagorno-Karabakh city of Shusha (Shushi in Armenian), which was recently captured by Baku, to safeguard the area against a perceived Russian threat.

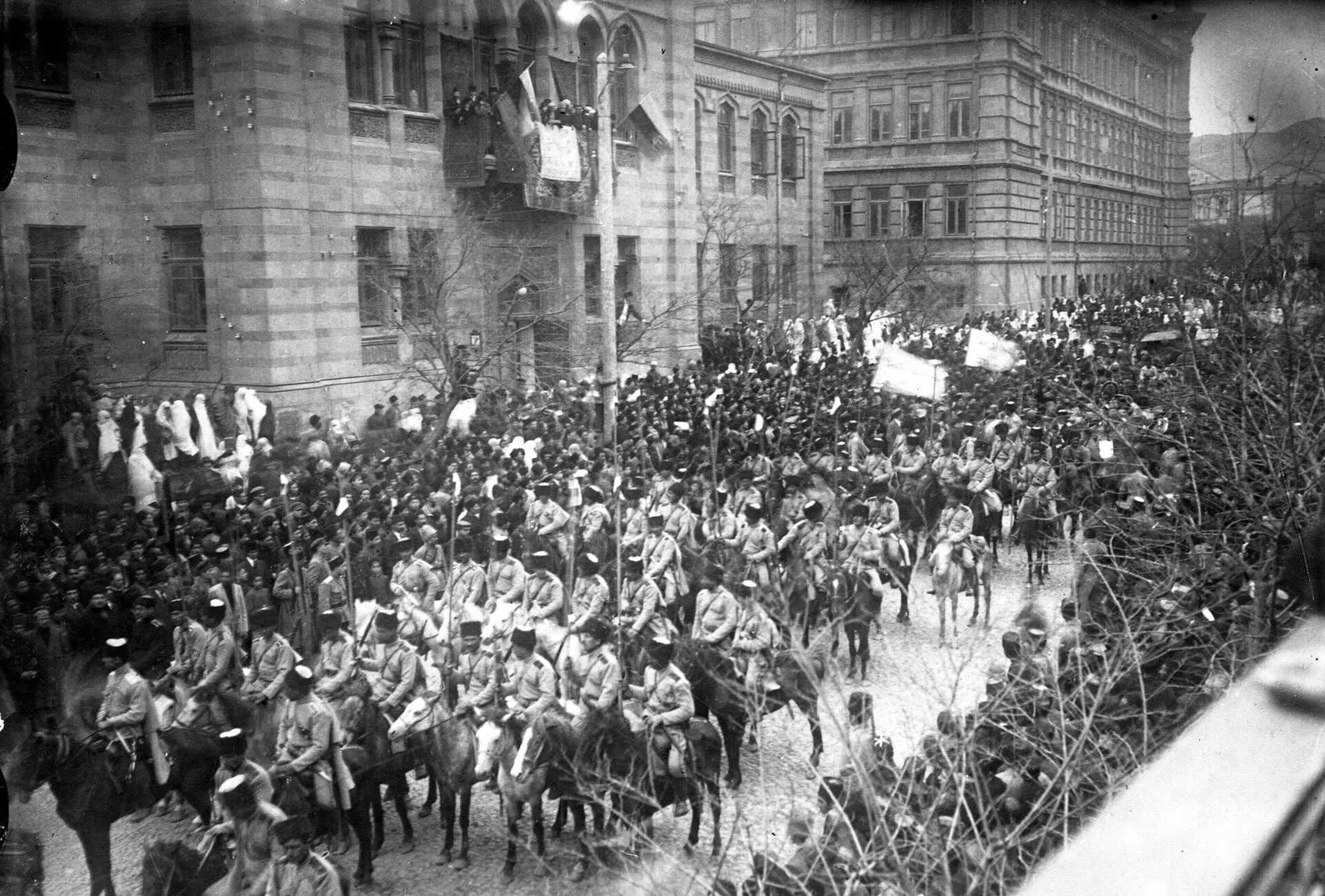

And on Thursday, Erdogan stood beside Aliyev during a military parade, celebrating victory in a conflict marred by shocking human rights abuses on both sides.

A hundred years after the Ottoman army seized Baku, Turkey had returned to Azerbaijan. You wouldn't guess it from the outpouring of fraternal feelings, but it marks a stark and abrupt change in the country.

'Azerbaijan asked for help'

Ten years ago, “liar, cheat and betrayer” were the words used by Aliyev to describe Turkish officials, after Ankara sought to normalise relations with Armenia. That broadside against the Erdogan government came in meetings with senior US officials, according to diplomatic telegrams released by Wikileaks.

Meanwhile, protests in Baku railed against Ankara for seeking normalisation with Yerevan without leveraging anything for Azerbaijan regarding Nagorno-Karabakh.

Now, things couldn't be more different, as - daily - Aliyev calls Erdogan his trusted brother and Azerbaijanis of various political stripes urge Turkey to establish military bases on their own soil.

The question, asked over and over by foreign diplomats as they attempt to decipher this volte-face, is "Why now?"

“Because Azerbaijan asked for help,” said a senior Turkish official, speaking on condition of anonymity. “It is that easy. There is no broader conspiracy.”

Turkey-Azerbaijan relations: A timeline

+ Show - HideHow Turkey and Azerbaijan’s relations went from frosty to familial in 10 years:

April 2009: Provisional agreement to normalise ties between Turkey and Armenia announced

May 2009: President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan boycotts an international meeting hosted in Istanbul

October 2009: Turkey and Armenia sign Zurich protocols to normalise their ties. Azerbaijani officials condemn it as against their national interests

November 2009: Turkey takes a step back and says it won’t normalise its relations with Armenia until Yerevan withdraws from Nagorno-Karabakh

January 2010: The Constitutional Court in Armenia approves the protocols but effectively restricts the authority vested on the planned subcommittee on the Armenian Genocide claims

August 2010: Turkey and Azerbaijan sign a strategic and military cooperation deal, a starting point of annual drills between the two countries

October 2011: First Turkey-Azerbaijan strategic cooperation council held in Izmir

December 2011: Turkey and Azerbaijan sign Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) deal after Ankara cools down the Armenia reconciliation

June 2012: Turkey, Azerbaijan and Georgia establish a trilateral diplomatic mechanism to deepen cooperation

May 2013: Azerbaijan state oil company begins to build STAR refinery in Turkey, valued at $4bn

November 2013: Baku allows visa-free travel for Turkish businessmen

April 2016: Azerbaijan and Armenia clashes turned to a full-scale conflict. Armenian media outlets close to the government claim Turkish military advisers are closely supporting the Azerbaijani army

October 2017: The Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway (BTK) is completed

June 2018: TANAP is completed

September 2018: Azerbaijani company close to Aliyev establishes Haber Global news channel in Turkey

Nagorno-Karabakh and seven surrounding regions have been occupied by Armenian forces since 1994, despite the multiple UN Security Council decisions that determined that the area belonged to Baku. Both the Armenian and Azerbaijani communities have long historical and cultural roots in the mountainous region.

Sporadic clashes have broken out since the 1990s, most recently in 2016 and in July, but essentially Nagorno-Karabakh was a frozen conflict until Ankara decided to get involved.

In various interviews, Turkish officials have underlined to Middle East Eye that the peace process run by the international "Minsk Group", headed by France, Russia and the United States, has been useless for the past 30 years. It was time, they said, for a new approach.

Turkey and Azerbaijan have strong ethnic links, as they speak almost the same language and share a common history.

“Is it weird that we tried to help our brethren?” asked the Turkish official.

Diplomatic vacuum

Turkish officials are quick to say that, despite the conflict being advantageous for Ankara and Baku, it was Armenia that sparked the latest war.

In July, Armenian forces attacked the strategic Ganja Gap in northern Azerbaijan, killing a general and his aides, who had been trained by Turkey. Armenia's defence ministry said at the time that the clashes began after Azerbaijani forces tried to cross the border illegally.

Matthew Bryza, a former US ambassador to Azerbaijan, said the attack left a diplomatic vacuum in the Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict, which indicated that Yerevan was going to have a more aggressive approach.

“It was clear that neither the US nor France would play any role in mediating that uptick in violence," Bryza told MEE. "Russia filled in on the Armenia side, and Turkey filled in on the Azerbaijan side."

Bryza added that, in August, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan "suddenly and foolishly" began talking about the Treaty of Sevres, a 1920 settlement that would have handed eastern Turkey to Armenia.

“I think that upset President Erdogan and others at the top of the Turkish leadership. Protecting yourself, that’s a strategic response by Turkey.”

Others believe Pashinyan had been ramping up tensions in the region since the beginning of this year.

“Pashinyan said that Nagorno-Karabakh was Armenia and there wasn’t any need for further talks,” said Ceyhun Asirov, an independent Azerbaijani journalist and expert on Caucasus. “It was really astonishing. People felt violated as he continued to encourage illegal settlements by ethnic Armenians in occupied Azerbaijan soil.”

Asirov said that the July attack on the Ganja Gap was extremely concerning for Azerbaijan, as well as Turkey.

“Armenian forces attacked the area where you have an energy corridor with Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline, TANAP gas pipeline and Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway,” he said. “This is the lifeline for Baku and a crucial energy and trade line for Turkey.”

The attack prompted protesters to pour into Baku's streets and demand revenge in unprecedented numbers. Some of them even broke into the parliament. Turkish flags were waved in the city's squares.

“People publicly asked for Turkey’s help during the protests,” Asirov added.

Overcoming differences

Gubad Ibadoghlu, the leader of opposition party Movement for Democracy and Prosperity and a professor at Rutgers University, said the attack revealed Azerbaijani weaknesses.

“It showed everybody that we needed Turkey to face the Armenian threat,” he said.

Over the years, Turkey and Azerbaijan had overcome their differences.

First, the Turkish government dropped the normalisation process with Armenia after a strong intervention by Aliyev, who sent Azerbaijani MPs to Ankara in October 2009 to pressure Turkey into abandoning reconciliation.

Later, Erdogan and Aliyev moved their relationship to a new level, eased by the construction of the Trans-Anatolian gas pipeline (TANAP), which strengthened Turkey’s role as an energy hub in the region by transferring gas to Europe.

'The West in time has distanced from Azerbaijan due to its repressive domestic policies'

- Arastun Orujlu, ex-Azerbaijani intelligence officer

Azerbaijan’s state oil company SOCAR, meanwhile, has nearly $20bn of direct investments in Turkey, which purchased strategic assets such as petrochemical company Petkim and built an oil refinery called Star. An Azerbaijani media company with close ties to Aliyev also launched a news channel, Haber Global, in Turkey in 2018.

Arastun Orujlu, a former Azerbaijani intelligence officer, said Aliyev also changed course in his foreign policy.

“The West in time has distanced from Azerbaijan due to its repressive domestic policies,” Orujlu said. “He had to make a course correction in 2015. Aliyev has been balancing Russia with western support. He is now in need of Turkey to do so.”

Fertile ground

Turkish officials say by the time clashes erupted between Azerbaijan and Armenia last July, the preparations for an annual joint military drill with Baku were already underway.

“We have already had F-16s deployed in the country and then there was a ground military drill with tanks and everything else,” the official added.

A second Turkish official said the 2020 presidential elections in the United States had created fertile ground for Ankara to craft a plan for Baku to capture the territories. While Washington and the rest of the world were distracted by the elections, Azerbaijan suddenly had enough time and space to make its move.

“We have offered to sell them armed drones since last year. But our Azerbaijani counterparts refused to purchase them,” said a third Turkish official.

“They had considerations with the western powers and it could be even about Israel. They didn’t want to damage their relations. But now they were in need, almost forced to get our help by the circumstances.”

Turkey had many perks to offer: a batch of seasoned armed drones that could destroy the heavily fortified battlefront; a strategy shaped by experienced senior commanders who had fought in Syria and Libya; advanced weaponry such as precision-guided missiles; and Syrian mercenaries that added to the boots on the ground.

For everyone in Ankara, it was almost natural for Turkey to do something for Azerbaijan. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Turkey had always wished to expand its role in the Caucasus and Central Asia, where a number of Turkic republics emerged.

Asirov, the journalist, said Turkey has been excluded from the Caucasus since Ottoman times.

“Turkey has always been part of the Minsk Group, but Russia and Armenia have always blocked Turkey from getting any meaningful role,” Bryza, the former ambassador, said. “Turkey has long aspired to have [access] to Azerbaijan and all the way to the Caspian Sea.”

There were some obstacles before Turkey as well.

Turkish officials had strong suspicions about Russian influence in Azerbaijan and its army, with which Moscow had long-standing deep ties, according to several Azerbaijani experts.

They suspect pro-Russian factions in Azerbaijan's army passed information to Armenia ahead of the July attack on the Ganja Gap, including intelligence on the exact location of high-ranking Azerbaijani military officers.

“The war in 2016 also indicated that there was a pro-Russian faction within the Azerbaijan army,” said Ibadoghlu. “Russian influence is high in the judiciary, military and the police."

Necmettin Sadikov, chief of general staff of the Azerbaijani armed forces, is considered among the pro-Russian ranks.

Suspicions that Armenia received intelligence from Russia have been made public. An article on the website of a think tank led by Erdogan’s close military advisor Adnan Tanriverdi in October accused Sadikov of leaking the location of the Azerbaijani officers in the Ganja Gap.

Since last summer, Sadikov, who had been the top Azerbaijani commander for 27 years, has disappeared from sight, and rumours suggest he was informally dismissed from his role.

Ibadoghlu said another high-ranking official, Baylar Eyyubov, chief of the security service for the president, has also disappeared. Several reports allege that he was previously accused of helping some members of the PKK, the Kurdish separatists who have waged a deadly decades-long war against Turkey.

Gateway to Central Asia

Once the operation started against Armenia on 27 September, the Turkey-backed Azerbaijan army slowly progressed from the south and made concrete gains. However, the pace wasn’t particularly satisfactory for officials in Ankara, where many questioned the training and the reliability of the Azerbaijani army.

Another concern for Turkey was Russia. It was an open secret that Turkey's leadership knew Russian resistance against Azerbaijan's operation could put a stop to the entire offensive.

In October, a Turkish delegation visited Moscow and realised that Russian President Vladimir Putin had no quarrels with Turkey's aims. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov described Shusha as an “Azerbaijani city”, and only conveyed criticism over the deployment of Syrian mercenaries, according to the Turkish officials.

As the Azerbaijani army neared Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh known as Khankendi in Azerbaijan, Armenia agreed a ceasefire brokered by Russia and supported by Turkey.

“We weren’t part of the negotiations as the deal was getting drafted, but we were consulted,” said the first Turkish official.

One of the 10 November deal's conditions was the opening of a road between Nakhcivan, an Azerbaijani enclave, and Azerbaijan proper, going through Armenia and creating a direct transportation link between Ankara and Baku.

“Everyone thinks this is a strategic victory for Turkey, as if we wanted it,” said the first Turkish official. “We didn’t even know anything about it until we saw the final version of the deal. Yet, we are happy about it.”

However, there was another condition which sparked a huge controversy in Azerbaijan, which was the deployment of Russian forces to Nagorno-Karabakh as a peacekeeping force.

“There has never been a Russian force in Azerbaijan since the fall of the Soviet Union,” said Orujlu. “They aren’t just a ceasefire mission. They have heavy weaponry, they are building permanent military bases that have drones and everything. Russian influence in the region and Azerbaijan will be directly felt.”

Ibadoghlu, the Azerbaijani politician, said the so-called Nakhcivan corridor would also serve Russian interests. “Moscow is trying to have direct access to Iran, as they are trying to extend their influence towards the south,” he said.

Many of Turkey's Nato allies blame Ankara for facilitating a victory for Russia, which didn’t even fire a bullet. There is near consensus in Azerbaijan that a permanent Turkish military presence in the country near Nagrono-Karabakh is needed to balance the increasing Russian influence.

'This is a huge geopolitical shift in Turkey’s favour and I would argue in Nato’s favour'

- Matthew Bryza, former US ambassador

Ankara seems unphased by Russia's presence in the region. Turkey and Russia reached a deal to establish a joint ceasefire observation centre near the Karabakh border earlier this month, but the terms of the deal have been kept secret. “It is only a regular ceasefire observation mission, nothing more,” said the first Turkish official.

Even though it might have helped Russia gain a foothold in Azerbaijan, many in Turkey and in the West believe that the conflict cemented Turkey’s power and role in the region.

“This is a huge geopolitical shift in Turkey’s favour and I would argue in Nato’s favour,” Bryza, the former US ambassador, said. “Turkey’s involvement in the Caucasus politically and militarily is a good thing, and I would argue that it is unequivocally a good thing for Nato.”

Orujlu agrees. “Turkey has given an example to the neighbouring Turkic countries that it was reliable and effective,” he said.

“Azerbaijan's people would like to see Turkish soldiers on their soil. This could become a gateway for Turkey to Central Asia.”

Photo: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan makes a speech during a military parade to mark the victory on Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, in Baku (Reuters)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].