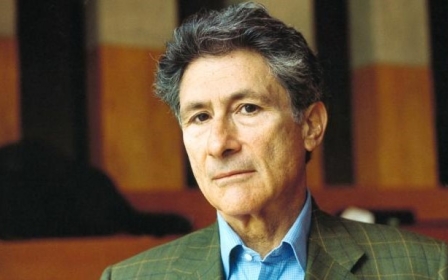

Worlds apart: Edward Said and Amos Oz on Palestine

This month marks the second anniversary of the death of Amos Oz, perhaps Israel’s most internationally recognised cultural figure.

On the surface, Oz occupied a position somewhat parallel to that of the late Edward Said (who died in 2003) in Palestinian society. Both were respected literary figures, regarded as spokespeople for their respective political causes: in Oz’s case liberal Zionism, and in Said’s the struggle for Palestinian liberation.

Oz lived in Israel his whole life, citizen of a country that systematically denied the right of return to the Palestinian refugees of 1948 and their descendants

Both criticised their respective national leaderships, with Oz called a traitor by the Israeli right and Said’s books getting banned by the Palestinian Authority in the 1990s. Both also had reputations - deserved or undeserved - as voicing humanistic positions, able to see the shared humanity of “the other”.

Said and Oz were both born in western neighbourhoods of Jerusalem in the twilight years of the British Mandate - Said in 1935, Oz in 1939. While British colonialism and mass Jewish immigration provoked a Palestinian uprising from 1936 to 1939, the Jerusalem of Said’s and Oz’s childhoods was still one of coexistence. As Said notes in his memoir Out of Place, he was delivered by a Jewish midwife.

The young Said and Oz might have unknowingly passed each other on King George V Street, the thoroughfare connecting the neighbourhoods of Talbiya, with its elegant Palestinian villas like Said’s family’s, and Kerem Avraham, where Oz grew up among Russian Jewish immigrants.

Yet, any shared experience of childhood was torn apart by the Nakba, the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. Close to 800,000 Palestinians fled their homes, including in what became Israeli-controlled West Jerusalem, to overcrowded and impoverished refugee camps.

Oz noted in his semi-autobiographical A Tale of Love and Darkness that Palestinian homes in West Jerusalem would “fall empty, intact, into the hands of the Jews and that new people would come and live in those vaulted houses of pink stone and those villas with their many corniches and arches”.

Yet, Oz chose to dwell upon the “dancing, revelling, drinking, and weeping for joy” in Jerusalem’s Jewish neighbourhoods, rather than on Palestinians’ dispossession - and he continued to defend the events of 1948 throughout his life.

Losses in the Nakba

In contrast, Said wrote of the pain he felt “that the very quarters of the city in which I was born, lived and felt at home were taken over by Polish, German, and American immigrants who conquered the city and have made it the unique symbol of their sovereignty, with no place for Palestinian life”. Said did not return until 1992 through the privilege granted to him by an American passport.

Oz lived in Israel his whole life, citizen of a country that systematically denied the right of return to the Palestinian refugees of 1948 and their descendants.

Given Said’s losses in the Nakba, his ability to empathise with Jewish people who “regard Zionism and Israel as urgently important facts for Jewish life” was remarkable. Yet the paradox, as Said noted in his essay “Zionism from the Standpoint of its Victims”, was that the goals of “saving the Jews as a people from homelessness and anti-Semitism and restoring them to nationhood” necessitated the dispossession of indigenous Palestinians.

Initially supportive of a two-state solution and a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, in later years Said turned to a one-state solution to reconcile Palestinian and Israeli claims, recognising that “so tiny is the land area of historical Palestine, so closely intertwined are Israelis and Palestinians, despite their inequality and antipathy, that clean separation simply won’t, can’t really, occur or work”.

'We will have to sit as occupiers'

On the other hand, Oz, hailed as a “dove” of the mainstream Israeli left, resolutely advocated a two-state solution. Yet this position came with caveats. “For a month, for a year, or for a whole generation we will have to sit as occupiers,” Oz wrote in an Israeli newspaper, shortly after the 1967 Six-Day War that began Israel’s 53-year and counting occupation of Palestinian and Arab territory. “We have conquered them and we are going to rule over them only until our peace is secured.”

Regardless of his antipathy towards Israeli settlers on occupied Palestinian land, Oz maintained that the occupation was necessary for Israeli safety, ignoring both the right of Palestinian self-determination and the fact that the injustice of occupation constitutes a primary Palestinian grievance leading to resistance.

When he opposed the policies of successive Israeli governments, Oz’s concern was never for their Palestinian and Arab victims, but what he saw as those policies’ impacts on “the soul” of Israel, which he feared would be “torn in two”.

Unable to understand Israel’s rightward drift as a product of Zionism’s colonising mission, Oz lamented the loss of a supposedly egalitarian, secular Israel - which had only ever existed for the European Jewish elite, not for the impoverished underclass of Middle Eastern Jews, nor for the country’s Palestinian minority, who lived under military rule until 1966.

The legacy of Said

Oz never tried to understand Palestinian aspirations, arrogantly describing Palestinians as “a defeated and conquered enemy” and claiming - despite the myriad parallels between the Palestinian, African American and South African struggles - that “it is both false and foolish to represent the Israeli-Palestinian tragedy as a civil rights campaign”.

Said wrote trenchantly of Oz and others “whose views are routinely aired in the western media as representative of the peace camp, and do a brilliant job of concealing their real views of Palestinians (not so different from Likud’s) beneath a carpet of conscience-rending, anguished prose”.

With many young Palestinians are now turning towards a one-state solution, drawing inspiration from civil rights struggles and the legacy of Said himself

Yet, despite Oz’s views actually not diverging significantly from those of the ruling Israeli right, it was telling that he ultimately became an anachronism in his own lifetime: an increasingly lonely voice in Israel calling for a two-state solution, though with so many qualifications that such a state would be meaningless.

By contrast, with many young Palestinians (and some Israelis and international observers) now turning towards a one-state solution, drawing inspiration from civil rights struggles and the legacy of Said himself, 17 years after his passing, Said’s time may now be arriving.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].