Why the Muslim Brotherhood's rise to power in Egypt failed

One of the oddly difficult truths to grasp about the Arab uprisings is that they did not have to be the failure they appeared to be.

When looking back on major historical events in an effort to understand them, we intuitively tend towards teleological interpretations that ascribe eternal essences to protagonists, whose actions in particular circumstances could only have resulted in the events that happened.

It’s easy to forget the basic truth of history - that nothing is inevitable - when it comes to the whirlwind rise to power of the Muslim Brotherhood and its sudden collapse at the hands of the Egyptian military, such has been the tendency to write about the uprisings in defeatist terms.

The question of “what could have been” looms heavily over Victor Willi’s new history of the Brotherhood, The Fourth Ordeal, part of the Middle East Studies series of the Cambridge University Press. Coming on the 10th anniversary of the 25 January revolution and focused on the period of 1968 to 2018, Willi’s book stakes its claim as the successor work to Richard Mitchell’s classic The Society of the Muslim Brothers (1969), while also contributing to the plethora of Arab Spring books offering an insider’s look at the Egyptian Islamic movement’s dramatic rise and fall.

The evidence the author marshals is formidable: some 140 interlocutors, including past and present leaders, along with mid-level and rank-and-file members of the group, interviewed in Egypt from the beginning of the protests in 2011 to the immediate post-coup period in 2013, and as exiles in Istanbul and other European cities up to 2018.

To this base of oral history, the author adds the writings of Brotherhood founder Hassan al-Banna, some works of Sayyid Qutb (the group’s leading ideologue after Banna’s assassination in 1949), various memoirs of Brotherhood leaders and activists from the 1980s to the present day, and copious secondary literature.

Willi, a researcher who works at the World Economic Forum in Geneva, deploys this array of material to write an accounting of events that explains both why this mass movement rose to dominate the Egyptian political scene in 2011 and how it so spectacularly failed. His thesis is that the reconstitution of the Brotherhood after the persecution of the Nasserist era led to the creation of two distinct trends within the organisation, whose long struggle for control ended with the victory by 2010 of the side that was the worst placed to manage the Brotherhood through the uprising.

This faction was the most likely to make the series of catastrophically bad decisions that led to the 3 July 2013 coup and subsequent suppression on an unprecedented scale.

Three previous crises

This is the fourth ordeal referenced in the book’s title, as activists explained it to Willi, following three previous crises in the group’s internal narrative of its past: its dissolution in 1948, leading to Banna’s death; the first Nasserist crackdown; and the trial and execution of Qutb and his followers in 1965-66.

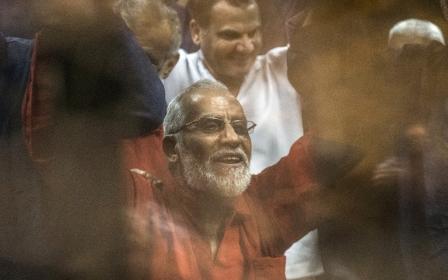

The old guard included Mustafa Mashhur and Mamun al-Hudaybi, who died in office as general guide in 2002 and 2004 respectively; Mohammed Badie, the current leader who assumed the position in 2010; Mahmud Ezzat, the acting leader after Badie’s arrest in 2013; London-based Ibrahim Munir, who became acting general guide after Ezzat’s arrest by Egyptian authorities last year; deputy leader Khairat el-Shater, who is in prison; and Mahmoud Hussein, who is in Turkey.

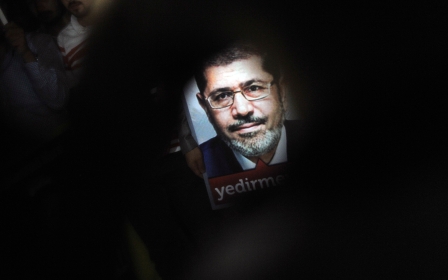

In the months that followed, the Morsi presidency was, in Willi's words, 'not much more than a race to the bottom', as various domestic and regional players conspired to force him from office

They shared memories of prison in the 1960s and in some cases of Banna’s life. But more than this, they favoured a conservative, authoritarian approach that explains why later figures, such as Shater, were able to bond with them. This approach privileged the societal work of expanding membership and overt religiosity over the political goal of forming a government through party mobilisation and positive engagement with rival political forces.

The latter was the vision of Umar al-Tilmisani, the general guide who masterminded the Brotherhood’s successful policy of contesting parliamentary and professional syndicate elections in the 1980s.

The old guard stands accused, in Willi’s work and elsewhere, of responsibility for several broad mistakes that led to the coup and the crackdown: shunning the 2011 protests at their beginning; quitting Tahrir Square after former President Hosni Mubarak stepped down; failing to make a common struggle with activists from groups outside the Brotherhood in ensuing clashes with the police and military; and former President Mohamed Morsi’s presidential decree of November 2012, which reflected the group’s obsession with framing a constitution to their liking and naive faith in the good intentions of the military and the willingness of the US to guarantee the new order.

In the months that followed, the Morsi presidency was, in Willi’s words, “not much more than a race to the bottom”, as various domestic and regional players conspired to force him from office.

Prison, seclusion and exile

Willi brings out striking details about the post-2013 fallout within the Brotherhood as different wings contended over leadership and policy across boundaries of prison, seclusion and exile.

Before security forces shot him dead in October 2016, Mohamed Kamal had managed to lay the groundwork for a renegade guidance office to match the official guidance office, by organising elections in which governorates controlling 270,000 members followed his directive, while the leadership abroad managed to order governorates controlling 300,000 members not to take part, and locales covering 200,000 members stayed neutral.

Such an organisational capacity and the numbers involved make it clear that the Brotherhood is far from crushed. Willi’s sources reveal other arresting tidbits, such as that 1,000 Egyptian Brotherhood members entered Syria from Turkey in the early stages of the civil war, and two-thirds of them joined the al-Qaeda-linked Nusra Front - or that activists recorded 85 cases of rape by Egyptian security personnel in the two years after the coup.

Willi’s sources seem to lean heavily towards the reformist camp, which perhaps leads him to minimise the dilemmas that the binary division of old guard versus reformers runs into in the post-coup era, when rival camps claimed leadership of the organisation. While the argument that the reformers had a vision that would have better managed the uprising is convincing, the question of violence complicates the issue once the fourth ordeal ensues.

The old guard’s gift for survival leads them unequivocally away from the path to violence as a response to state brutality. In this, they apply nothing more than the lessons of history. Qutb’s famous Milestones, contrary to popular representation, was not a manifesto for jihadist war on ruling regimes, but for a vanguard elite to withdraw from profane society in preparation for a time when conditions were more propitious for mass acceptance of his utopian Islamic system. Violence is only explicitly considered as a response to state efforts to hunt down the vanguard.

It may be easier for leaders abroad to preach forbearance from their comfy exile in Istanbul, Doha or London, but it is hard to see what long-term benefits there would be to sanctioning the assassinations, or “special qualitative operations” that the second-rank leadership on the ground in Egypt approved - as Willi establishes - in mid-2015.

Nothing inevitable

A major conundrum also remains unresolved. Why did a secretive clique that devalued public political work insist on running a full panoply of candidates in the 2011 parliamentary elections (through the Freedom and Justice Party), then on running one presidential candidate (Shater) followed by another (the ill-prepared Morsi) when the first’s nomination was struck down by a court?

When it ventured into the political space it had long disparaged, the Brotherhood proved unsurprisingly incapable of sensibly weighing its decisions and interactions with other social and political forces, sidelining those who had gained experience in just that sort of activity.

The Brotherhood failed to transition effectively from the mode of opposition to that of revolution because they could not appreciate the historical moment for what it was

It is a problem that has plagued the group since its earliest days: building a mass movement only to equivocate over the exercise of the power amassed. Former President Gamal Abdel Nasser felt he had no choice but to crush such a popular force if it was not going to back him, but the military six decades later was only able to turn on the movement once it had proven itself incompetent in governing. There was nothing inevitable in any of this.

Political Islam is not over, but it clearly has issues. Willi points to two starkly different celebrations of the Brotherhood’s 90th anniversary in 2018: Munir delivered the keynote speech at a swanky gala in Istanbul, with a typically lacklustre performance whose major message was the fact of the group’s survival.

The renegade guidance office, on the other hand, issued a document titled “Vision 28” - a critical review of mistakes committed and an outline of a way forward that would be requisite for any self-respecting political movement of the Brotherhood’s stature, but that the leadership has effectively suppressed. It concludes that the Brotherhood failed to transition effectively from the mode of opposition to that of revolution because they could not appreciate the historical moment for what it was. Like any other moment, it was ephemeral.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].