Ripple effect from corruption charges yet to be seen in Turkey

Four former Turkish cabinet ministers must have taken a deep sigh of relief on Monday evening at the news that they are not to go to trial in Turkey’s “High Council”, a special supreme court which tries ministers and some top officials for serious irregularities. The decision, passed in a 9 to 5 vote by a parliamentary committee of investigation, brings to an end the biggest political upset Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) has suffered during its 12 years in power. But it does not mean that full stability has yet returned to Turkish politics. The government still lists as its top priority the fight to eradicate the Gulen movement - a modernist Islamic Brotherhood group in the US - from public life.

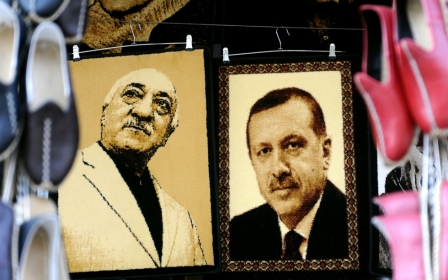

The corruption crisis began in mid-December 2013 with a sudden wave of arrests of figures close to the AKP on allegations which included the illegal trafficking of one and a half tons of gold in an “oil-for gold” deal between Ghana, Turkey, and the Gulf, brokered by a Turkish Iranian businessman. The charges were strenuously denied and the government claimed angrily that the arrests were an attempt to overthrow it by prosecutors, police, and judges linked with the Gulen movement. Its discomfiture was made greater by the appearance on the Internet of a series of secretly taped conversations purporting to be between Recep Tayyip Erdogan, then prime minister, and one of his sons.

However, the government quickly regained control and launched a drive against its accusers. What followed has changed the face of Turkish national life and introduced a much more restrictive political climate.

Several thousand officials suspected of disloyalty were reassigned to marginal posts. Some were dismissed and others may even face prosecution. Laws on the judiciary and the Internet, and later on homeland security, were drastically modified to bring possible opponents under stricter control. The word “coup” became one of the most over-used in Turkey. It appears that any attempt to get a change of government in any way amounts to a “coup”.

Not only were the corruption investigations denounced as a coup, but last week, senior government politicians including a serving minister, were claiming that attempts to have the ex-ministers tried in the Supreme Court amounted to a coup attempt.

More generally, the government has shown extreme sensitivity over what it regards as unfounded accusations. The word “thief” has been frequently used by the opposition and by protesters - but doing so generally leads to trouble. Even the brandishing of a shoe box in the street ($4.5 million dollars were discovered in a shoe box in the home of the chief executive of a state bank during the investigations) was regarded as sufficient to warrant detention and questioning. A television announcer who posted a tweet last month about the case is being questioned by police. The government spokesman insists, however, that democratic freedom of expression has not been curtailed, saying international claims to the contrary are fueled by the Gulenists.

Charges against most of those arrested in December, 2013 were dropped and the cases closed in the following six months. In December, a final appeal against the closure of the cases was also overruled, leaving only the four ex-ministers facing possible proceedings. Full details of the investigation into them in the National Assembly are not known, because when it began its meetings in September, the government ruled that they could not be reported in the media. One of its members, representing the Kurdish-led Peoples’ Democracy Party, then walked out in protest. Five other opposition party members stayed on, though with a large AKP majority on the committee, the outcome of the investigation was never in much doubt.

However, inside the AKP itself, there seem to have been at least two distinct views about the course to be taken, with some voices arguing that at least some of the ex-ministers should face trial in order to satisfy public opinion. Within the committee, it seems that some members were disturbed by the findings of a civil service enquiry into the personal wealth of the ex-ministers – though details have not been made public.

On 21 December, then prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu reiterated the AKP’s firm opposition to all forms of corruption, saying that even if our own brother does it, “we shall cut his arm off”. When the following day, the committee was unable to vote on a decision, the prime minister’s words suggested to opposition press commentators that AKP opinion was divided, and even that there was a split between the president and the prime minister. Speculation along these lines were boosted when the president of the Grand National Assembly, Cemil Cicek, also hinted that a trial might be the best way out.

This suggestion was later strongly denied by Bulent Arınc, the deputy prime minister, calling it absurd. Nevertheless, the committee vote was deferred until 5 January when, again after a delay on reaching a decision of several hours, it was announced that the four ex-ministers had been cleared. Asked if there had been any pressure on the committee, Hakkı Koylu replied, “What pressure do you mean? Who’s going to put pressure? What pressure would there be?”

There matters are likely to rest, though the committee’s report must be submitted to a full session of the National Assembly and voted on before 29 January. In theory, the house could still send the ex-ministers for trial - but 52 AKP deputies would have to defect to the opposition for this to happen.

The government’s eyes are now focused on the general elections to be held in the first half of June. These are important, not just because the government needs its 50 percent vote as kind of plebiscitary endorsement of its actions to face down its opponents, but also because if it can get a two-thirds majority in the new assembly, it will be able to change the constitution at will.

The corruption crisis is now probably part of history. The ex-ministers, one of whom has appeared together with President Erdogan on a balcony, may even return to public life. But the crisis has left Turkey deeply divided and demoralised, and with a much more authoritarian style of government. The hunt against the Gulenists goes on, as shown in the recent crackdown on the Guenist media. All this adds up not to a more stable and secure society, but to an angry and politically fragile one.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].