Vaccine alliance: How Cuba and Iran are joining forces to battle Covid-19

In 1959 when Fidel Castro declared victory of the Cuban Revolution, his first promise was socialism. His second pledge was to turn Cuba into a global leader in science and health.

Cuba’s domestic development of a Covid-19 vaccine marks the latest step in this trajectory. And in line with Cuba’s health internationalism, this has resonated in the Global South.

Iran and Cuba recently established a collaborative framework under which the Cuban vaccine will be developed between Iran’s Pasteur Institute and Cuba’s Finlay Vaccine Institute. This alliance is strategic for a number of reasons. Both countries are under stringent US sanctions, with Cuba freshly added to the US State Department’s list of “terrorism sponsors”. The partnership with Tehran is also a critical test of the Cuban vaccine’s efficacy.

US and UK vaccines banned

While Cuba’s vaccine trials have been largely successful so far, the country’s infection rate is too low to provide a fulsome test, so Phase III trials will be carried out on 50,000 Iranians. Iran was among the hardest-hit countries in the Middle East amid the coronavirus pandemic. If ultimately successful, the Cuba-Iran vaccine could be available as early as this spring.

The Cuba-Iran vaccine venture comes after Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei banned the use of vaccines produced in the US and UK. Cancelling 150,000 donated doses of the Pfizer vaccine from the US, Khamenei said: “Imports of US and British vaccines into the country are forbidden … They’re completely untrustworthy.” Vaccine doses will instead be imported from countries with closer ties to Iran, including Russia, China and India.

The hard reality of vaccine geopolitics is that some countries will have privileged access - particularly western countries, Israel and rich Arab monarchies

While health officials have warned against “politicising” the Covid-19 pandemic, politics and geopolitics remain crucial determinants of vaccine strategies. Khamenei’s suspicion towards western health programmes is part and parcel of his distrust of American and European states on all matters of international cooperation. The failure of the nuclear deal, along with US and Israeli assassinations of Iranian officials, have only buttressed this conviction.

His remarks also hearken back to France’s contaminated blood scandal in the 1980s, when Iran and other countries imported HIV-infected blood from France. Iran’s first HIV cases reportedly followed, and by 1993, around 1,800 Iranians had contracted hepatitis and HIV, according to Iranian media.

Public confidence

Vaccines require high levels of public confidence, lest they be undermined in the objective to eradicate the spread of a virus. Khamenei’s rejection of American and British vaccines could cast doubt on future vaccination programmes, as people may worry they are not getting the best available immunisation amid the ideological calculi of their political leaders.

Trials and scientific data are the only guarantors for successful immunisation. But the hard reality of vaccine geopolitics is that some countries will have privileged access - particularly western countries, Israel and rich Arab monarchies - while many others will need to find alternative routes that are built on local potential or international solidarity networks.

Pharmaceutical companies and transnational investments have enabled the rapid development of American and European vaccines, while the Cuban-Iranian programme is built on homegrown, indigenous efforts. It is no coincidence that both Cuba and Iran are recognised as having among the most advanced medical and pharmaceutical industries in the Global South.

History provides examples of health solutions emerging not from western capitalist investments, but from research in the Global South. One example is the polio vaccination programme in which Cuba became “the first populous country to eradicate wild poliovirus in the western hemisphere”.

On the strength of its success and in line with Castro’s vision of the revolutionary force of doctors, Cuba led by example in the eradication of polio in Latin America. This was also part of a broader movement of socialist internationalism, whereby Cuban doctors and scientists would tour other countries to share their direct experience of inoculation programmes.

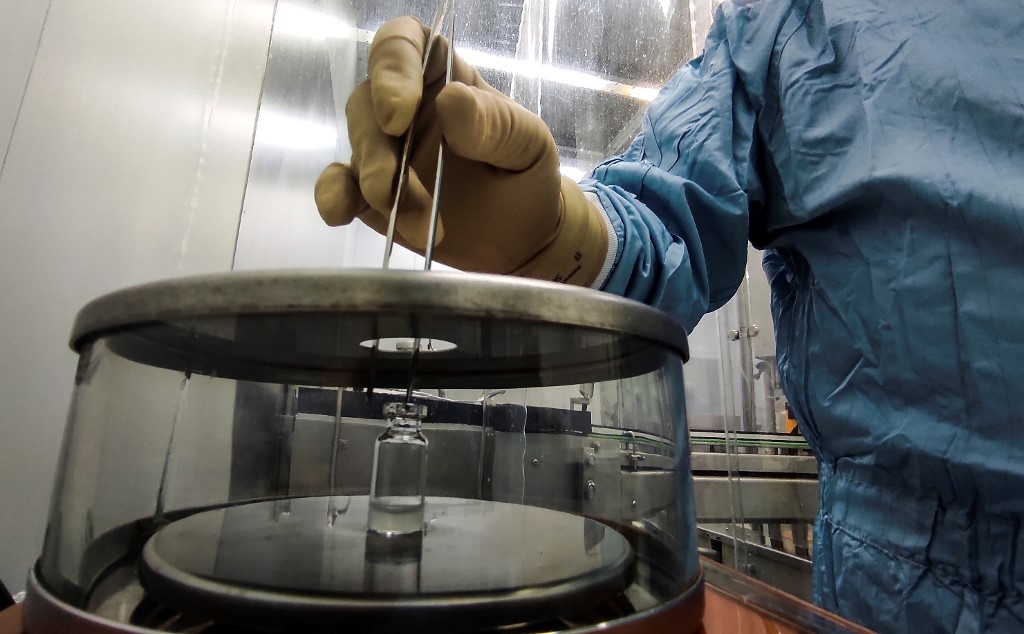

Mass production

The Cuba-Iran health cooperation is part of a broader strategy and they previously worked together in the production of a pneumococcal vaccine. Collaboration with Cuban scientists also helped in scaling up production of a Hepatitis B vaccine. Indeed, Cuba’s internationally recognised leadership in biotechnology is responsible for the dependability of its coronavirus vaccine trials.

Public health experts and immunologists have long repeated that the challenge is not only in finding an effective vaccine, but also in mass-producing one that can be distributed around the globe at a minimal cost.

Should the Cuba-Iran Covid-19 vaccine trials succeed, it would boost people’s declining confidence in Iranian public institutions and could also present a viable solution for other Global South countries at the mercy of “philanthro-capitalism”.

Cuba has indeed been faithful to its original revolutionary promise: “Medicos y no bombas” (“Doctors and not bombs”).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].