Sudan’s government promised to protect Darfur. Instead scores are dead

The United Nations withdrawal from Darfur should have been a moment for Sudan to turn the page on a bloody and bitter period of its history.

Instead, deadly violence broke out once again, severely undermining the Sudanese transitional government’s promise that it could protect its citizens in the war-torn southern province.

On the ground, Sudanese are scared. Clashes so soon after the 31 December withdrawal have sowed doubts about the peace agreement signed with some factions in the region in October, and suspicions are high that armed groups now reconciled with Khartoum will seek to increase their status.

'The mid-January attacks on civilians in West Darfur were the Sudanese government’s first big test of its readiness and ability to protect Darfuri civilians. It failed miserably'

- Mohamed Osman, HRW

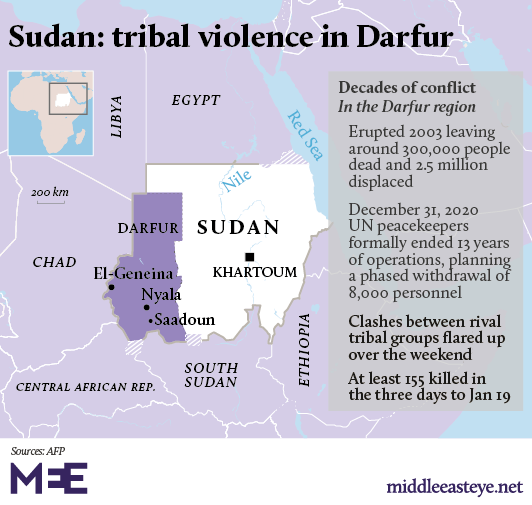

The recent clashes between Arab nomads and members of the Masalit ethnic community began in the city of Geneina in West Darfur state, near the border with Chad.

But very quickly they spread to the entire state and extended to South Darfur and other areas, killing more than 200 people and wounding of over 300 others, according to the Central Committee of Sudanese Doctors.

Mohamed Osman, Human Rights Watch assistant researcher for Africa, said the violence in Geneina has immediately exposed the transitional government’s capabilities on the ground.

“The mid-January attacks on civilians in West Darfur were the Sudanese government’s first big test of its readiness and ability to protect Darfuri civilians. It failed miserably,” he told Middle East Eye.

Old enemies

For 13 years Darfur, the scene of a devastating 2003 conflict between non-Arabs and Arab-dominated militias backed by then-President Omar al-Bashir, has been presided over by a joint United Nations and African Union peacekeeping force (UNAMID).

Some 300,000 people were killed in the conflict, with Bashir, who was ousted in a 2019 pro-democracy uprising, wanted by the International Criminal Court over war crimes and genocide charges.

However, the UNAMID mission ended last month, to the distress of many Darfuris, who suspected that the 12,000-strong peacekeeping force sent by Khartoum as a replacement would not be adequate protection.

It took just 16 days for deadly violence to erupt. On the ground, Darfuris believe old enemies and shadowy powers lie behind that violence.

Mohammed Adam, who witnessed the clashes first hand, believes security organs close to Bashir’s regime played a part in the violence.

Adam, a member of the revolutionary movement in Geneina that toppled Bashir, told MEE that some unknown agents believed to be close to the old regime distributed weapons to individuals during the clashes.

“This conflict is fabricated, because it began as very personal clashes between Masalit and Arab militias, and suddenly turned into widescale war because some agents fuelled it,” he said.

The clashes uprooted 50,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) from the Kerinding displacement camp outside Geneina, according to Save the Children, and though the killing has subsided since Khartoum sent reinforcements, looting has continued.

'The army saw the villages and IDP camps burned and the militias hunting down the people who fled the camps inside the city and didn’t move'

- Alamin Hassan Gibril, Geneina mayor

The Abazar, Tariat and Ardamatta camps were also swept up in the violence.

Osman Adam Khamis, who represents displaced youth in Darfur, told MEE it is illogical for such widespread violence to be sparked only by vengeance over a Masalit’s killing of an Arab.

“These kind of things are supposed to be resolved by the police, not with people taking the law into their own hands. Our people in the Kerinding IDP camp have faced brutal war without clear reasons, this is why we believe that the militias want to ignite the region,” he said.

Alamin Hassan Gibril, the mayor of Geneina, said the situation now is relatively calm, but still unpredictable.

He accused the military leadership in West Darfur of intentionally delaying intervention for two days, which he said proved its links to the militias that attacked the IDP camps.

“The situation has been controlled after the government sent military reinforcements from outside the state after two days of clashes, but the army in the state turned a blind eye,” he told MEE.

“They saw the villages and IDP camps burned and the militias hunting down the people who fled the camps inside the city and didn’t move.”

MEE has contacted the army but received no response to its calls. Medical workers in West Darfur said at least 159 people were killed and over 160 wounded in the state alone.

Shift of power

Back in October, there were big hopes for Darfur.

A peace agreement signed between the transitional government and rebel factions in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, included big political and financial pledges for the region, including a $700m development fund.

Meanwhile, the 2021 budget earmarked $1bn for the implementation of the Juba agreement and other projects and services. It also included plans to compensate and return or resettle displaced people, which the UN estimates are around three million.

On top of financial investment, the Juba agreement contained security and justice provisions, including the creation of the new Sudanese peacekeeping force, which is made up of soldiers and former rebels.

A new special tribunal to prosecute the perpetrators of abuses in the Darfur conflict was also launched.

But great obstacles stand in the way.

The most powerful of Darfur’s rebel groups, the Sudan Liberation Movement - Abdul Wahid (SLM/AW), has refused to accept the agreement; a huge vacuum has been left by the UN/AU mission’s pullout; and the recent tribal clashes have only polarised communities further.

Abdallah Adam Khatir, political analyst and chancellor of the Zalingi university in Central Darfur state, told MEE that the agreement has caused a big shift of power. With some rebel groups reconciled and others not, the balance between ethnic groups has been altered.

“This peace is incomplete, and that may lead to another conflict of interests and polarisation among the different groups in the region. It could lead to serious consequences,” he said.

Gibril, the mayor, also believes the new force in Darfur will only lead to polarisation instead of peacebuilding.

“We don’t see any change since the ousting of Bashir. There is no civil rule anymore, the army and the militias are still controlling everything in the region, and the politicisation of the local leaders is another big cause of violence incitement,” he said.

“These forces aren’t disciplined and not neutral, so we are afraid that these forces may worsen the situation.”

Declaration of war

In the mountainous area of Jabal Marra, there are already signs that peace is fraying. On Monday, SLM/AW accused the Sudanese government of violating a three-year ceasefire and targeting its fighters.

In fact, the SLM/AM suggests the deployment of the new peacekeeping force amounts to a declaration of war.

“The labelling of the deployment as a ‘peacekeeping force’ is a manipulation, and will lead to serious consequences on the ground as there is no peace to be saved in the region, and these forces partook in the crimes against the people of Darfur,” SLM/AW spokesman Abdul Rahman al-Nair told MEE.

Nair said he has no confidence that the government is willing or able to implement real justice and peace in Darfur.

“We are not calling for violence or war, and we wouldn’t carry out any hostilities against these forces, but we would definitely defend ourselves if we faced any attack,” he added.

The group is preparing for that eventuality. Photos verified by MEE show graduate fighters forming a new battalion called the Eagles of Liberation in rebel-held Jabal Marra.

Alhadi Idriss, deputy chairman of the Sudanese Revolutionary Front, a rebel coalition now reconciled with Khartoum and providing troops for the peacekeeping mission, insisted the new force was there to protect civilians and improve security.

He told MEE that the force could even grow - swelling to 20,000 by including 8,000 more ex-combatants.

A Sudanese military expert, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said the government is in a critical position as it needs to prove to the world that it can fill the security vacuum after the withdrawal of the UNAMID mission.

“However, the deployment of joint government and rebel troops on the ground has become another factor that concerns tribes and rebels in the region and increases tensions, because of the shift in power it may lead to,” he said.

The expert warned that former rebels in the peacekeeping ranks and current rebels like the SLM/AW are likely to clash, and for those clashes to spread. Meanwhile, Arab pastoralist nomads continue to be a source of friction for the displaced.

“Many other deeply rooted obstacles to achieving peace in the region remain, as the displaced people feel unable to return home because their land has been occupied by pastoralist groups,” he said.

“And inter-communal violence and attacks against IDPs appear on the rise, as the transition in Khartoum shifts Darfur’s balance of power.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].