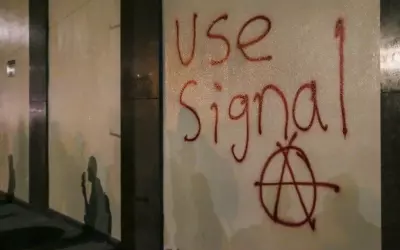

Signal is blocked in Iran and no one will admit to ordering it

Like many people across the globe, Iranians have been spooked by WhatsApp's recent announcement that it would be sharing data with parent company Facebook. In response, they have been flooding to the messaging app's rival, Signal.

This month, Signal became the most-downloaded app in Iran. On Monday, it was suddenly blocked and removed from local Android markets.

Signal is an encrypted end-to-end messaging app used by journalists and activists worldwide and considered the most secure app of its kind.

The huge rise in its popularity clearly troubled Iranian authorities. But amid the outcry over Signal's restriction, no one in Tehran's government or judiciary has taken responsibility for blocking the app, with a blame game rumbling on as Iranians bypass restrictions through VPNs.

Mass migration

This is not the first time Iran has witnessed a widespread migration on social media platforms.

In 2018, WhatsApp was the beneficiary when the judiciary banned one of its main rivals, Telegram. Iranians flocked to the app due to reports it had high levels of encryption, while authorities urged the use of local messaging apps, which are far less secure.

Telegram itself became popular when Viber was blocked four years before that.

Nasim Tavakol, who runs an e-commerce business, believes data security and privacy in Iran is a highly important issue for users.

'I will never use WhatsApp again because when they don't block an application, that means they are able to have access to people's data there'

- Mahsa, business administration graduate

"When WhatsApp announced that it was providing Facebook with users' data, concerns about information leaks among Iranian users, as well as Signal's announcement that it stored no information on the company's personal servers, led Iranians to migrate to this messaging application," Tavakol told Middle East Eye.

Conversations with Iranian Signal users quickly proves Tavakol's point.

Mahsa, a business administration graduate, told MEE: "I left WhatsApp because of its wrong policies, but even after the blocking of Signal, I will never use WhatsApp again because when they don't block an application, that means they are able to have access to people's data there. Despite the blocking, I will continue using Signal because it seems to be safe."

Mohsen, a political science graduate, also expressed suspicion over Signal's blocking. "The bottom line is that blocking will just increase people's distrust of the state," he told MEE.

Blame game

Privacy-seeking Iranians aren't the only people affected by the blocking of Signal. A political row has followed the restrictions, too.

Neither the government nor the judiciary is taking responsibility for the move.

Only the judiciary, whose chairman is chosen by the supreme leader, and a "working group" committee are able to block websites and applications in Iran.

The "Identifying the Criminal Content Working Group" consists of six government ministers and seven officials from other authorities.

The ministers of communication, culture, justice, science, education and intelligence make up the government's share. They are joined by a representative of the Islamic Propaganda Organisation, the attorney-general, the police chief, two MPs, and someone from the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution.

As chairman of the committee, the attorney-general, who is appointed by the judiciary, wields enormous influence.

Raja News, a hardline website close to the judiciary, quoted a source as saying the restrictions on Signal are related to a 2017 decision by the working group, though it gave no rationale for why they were being implemented now.

The news site also claimed that Iran's communications minister had voted in favour of the restrictions.

In response, Jamal Hadian, spokesperson for the communications ministry, denied the allegations.

Meanwhile, a spokesman for the judiciary said in a press conference on Tuesday: "The judiciary has not blocked any media, news agencies and messaging during the [recent] period and does not seek to block any of the social media messages."

The government against the judiciary

Signal is just one element of a broader row between the government and the judiciary over social media. Instagram, too, is in the eye of the storm.

Communications Minster Mohammad-Javad Azari Jahromi was summoned to court on 20 January over accusations he was not following the judiciary's orders on restricting Instagram and other foreign social media apps.

When Jahromi's summoning was leaked to media, the judiciary quickly denied it had anything to do with blocking Instagram. However, the communications ministry later released two pages of court documents proving the minister was indicted over refusing to filter Instagram.

Moreover, government spokesman Ali Rabiee used Instagram to warn about the consequences of blocking the app, saying it would push about a million Iranians into unemployment and poverty. Around 24 millions Iranians are thought to be on Instagram.

President Hassan Rouhani, a moderate, joined the fray. Rouhani responded furiously to Jahromi's summoning, saying on 27 January: "If you want to try someone, try me," and noting that social media are used as a tool to expose corruption.

Judiciary spokesman Gholam Hossein Esmaili replied angrily, sarcastically saying the government would do better to explain why people are suffering in dire economic circumstances.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, an analyst close to the government told MEE: "As Rouhani is close to the end of his tenure, the judiciary and hardliners are determined to make sure Rouhani has no encouraging legacy in order to make people totally pessimistic about reformists and moderates ahead of June's presidential elections."

According to the analyst, Rouhani has two legacies. "One is the 2015 nuclear deal, which is somehow in intensive care, and the other is his striving to keep social networks open and unblocked."

Tavakol, the e-commerce businessman, believes ordinary Iranians are being hurt in the row and are the first victims of restrictions on social media.

"Blocking means creating a monopoly, and when there is a monopoly, the competition ends. When the competition is over, the quality decreases because the local rivals are assured in every way," he said.

"Under such conditions, people are deprived of their choice. In the age of communication, we can't benefit from the digital economy while dealing with blocking. Unfortunately, blocking decisions are made irreversibly in our country. This issue will only harm the Iranian people."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].