In pictures: Blast-hit Beirut hospital battles to rebuild amid second Covid-19 wave

The sound of drilling is enough to blank out beeps from machines monitoring the intubated in all 13 cubicles of an interim coronavirus ICU at St George’s hospital, Beirut. The building was heavily damaged in the Beirut port explosion six months ago and now teams of construction workers are rebuilding the original ICU as medical staff battle to save the lives of Covid-19 victims in earshot of the building works (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

Coronavirus ICU occupancy is at 100 percent in the hospital and a third of staff have been struck down with Covid-19 so far, as a devastating wave sweeps through Lebanon following the easing of restrictions over Christmas and New Year. The patient pictured is in an induced coma and suffering severe circulatory problems (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

The hospital was devastated when an estimated 2,570 tonnes of ammonium nitrate unsafely stored in Beirut's port exploded last August, killing more than 200 people, injuring almost 7,000 and displacing over 300,000. "Everything was damaged: the walls, the ceiling, the windows, the glass, it was all down, the equipment was on the ground, everything, scattered everywhere," says George Kamel, site supervisor of the ICU rebuild. Six months on serious damage is still evident in the admissions department (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

Prior to the blast, St George’s had been running outpatient Covid-19 fever clinics, as well as administering blood work and scans. "After the blast we cleaned up and then opened the clinics again," assistant head nurse Misha Massaad, 30, says. Back then, they were only outpatient clinics, but all that changed as case numbers soared 6,000-fold and ICUs filled up. Builders work next to the fever clinic, which is still operating with plastic instead of glass in the windows (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

"For the past two months, we have also been receiving very critical inpatients to the clinic," says Massaad. Salim Nehme tested positive at 100-years old and has been on a trolley in the fever clinic on oxygen for two days, watched over anxiously by his daughter from the doorway of his cubicle (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

One clinic is currently closed because there are not enough people to run it due to staff Covid-19 cases. The other has an inpatient occupancy rate of 80 percent and an outpatient occupancy of 400 percent, according to Massaad, pictured here with her arm around a colleague.

"Personally I am exhausted," she says. "I was positive - today is my first day post-Covid. I got it here." She goes on to say she hasn’t seen her parents for almost a year because of the nature of her work. "They’re in our village and I’m living here with just my cat. It’s very difficult, especially on my birthday" (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

Massaad’s team has taken a big hit. "I still have three or four staff who didn’t have corona yet - the other 12 all did," she says, describing the inherent difficulties of managing a team that changes daily due to increasing occupancy rates and staff sickness. "They are run down, physically and psychologically from seeing this amount of people sick and knowing that when we transfer people to the ICU, often they pass away two days later," she says (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

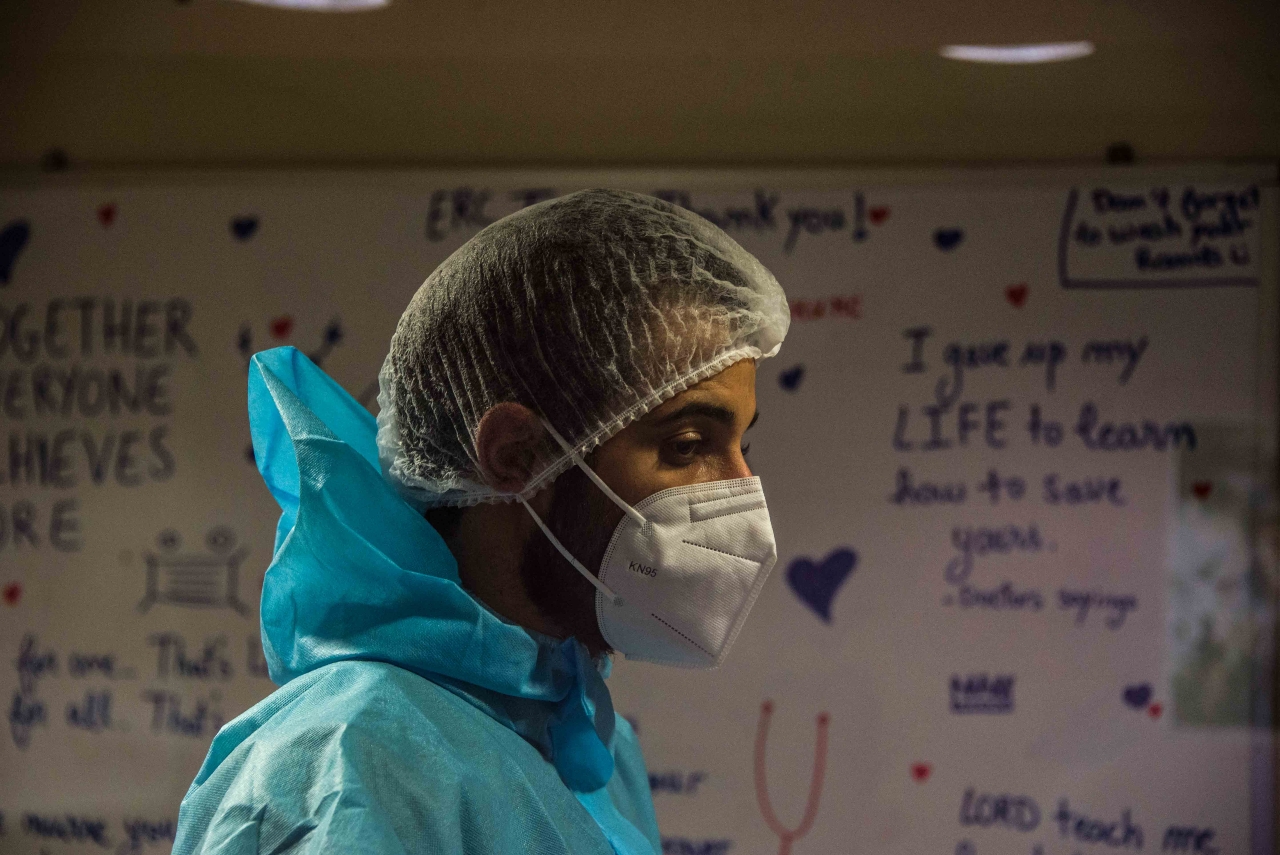

Exhaustion haunts the faces of those working in the ICU. Postures tell a story of extreme fatigue and tired eyes blink back tears. Nurse Anthony Abou Naoum, 24, describes the pain of working on the frontline of the pandemic day in, day out. He says these patients don’t just need medical treatment, they need company, encouragement and emotional support because they are completely alone, with no visitors allowed. "And this is what they have to also go through," he says, gesturing helplessly as the rumble of heavy drilling starts up again (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

"We get attached to these people because they don’t have anyone, they only have us," says Naoum, his voice wavering. "Maybe they’re doing well. But then suddenly they die. Over and over."

A nurse now for five years, he says that, "working with Covid patients has been the most difficult time ever. Emotionally, physically, it’s very stressful." He estimates that for every ten patients coming through his ICU, up to four do not make it out alive (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

Having noticed a patient staring at the same spot on a blank wall each day while doing his rounds, Naoum asked him why. "He said to me: 'Where else can I look? There’s only four walls'". So Naoum promised he would bring him something else to look at. "I brought him pictures of nature to put on his wall," says Naoum. "But the second day I came in he was dead. And he was only 42."

The nurse has now put pictures of the natural world on the walls of every cubicle, in an effort to do something more to ease the suffering of those trapped here (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

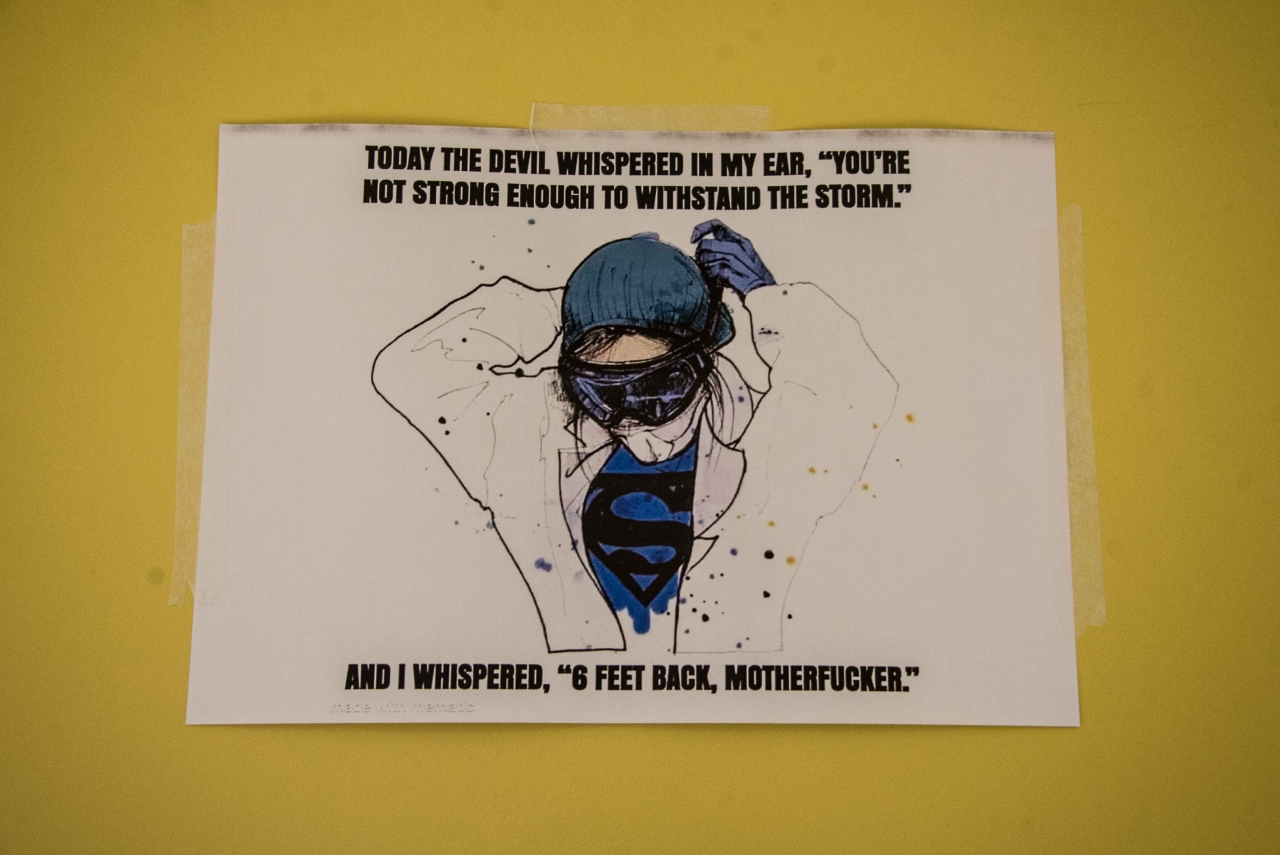

Staff are trying to lift their own flagging spirits as well. The corridors of the ICU are festooned with positive images and empowering posters, a whiteboard in the control room is covered in affirmations. Administering aphorisms represents a last line of defence in staff efforts to make it through the day with their sanity intact (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

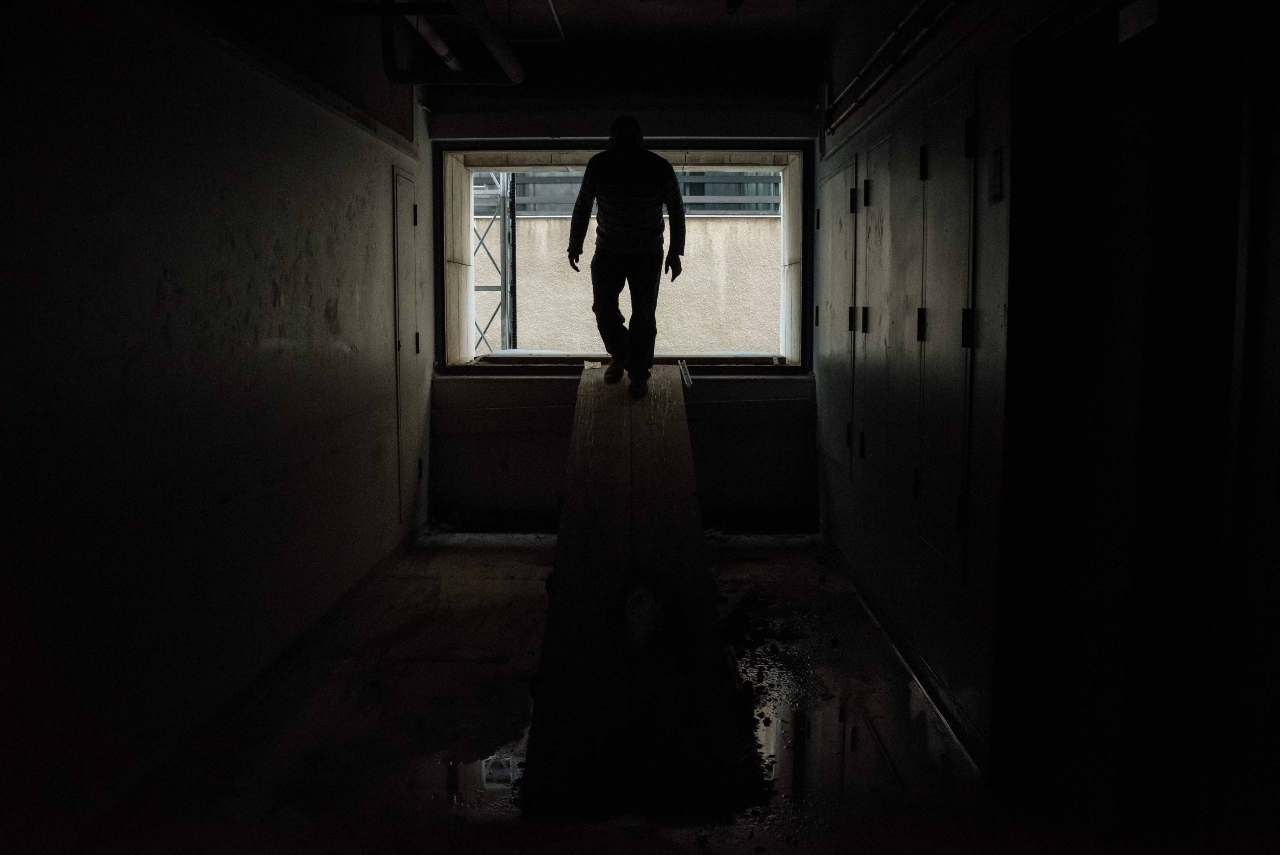

The rebuilding of the main ICU can’t come quickly enough, with plans to expand capacity from 12 cubicles in the old facility to 24 in the new. Begun in December 2020, Kamel, the site supervisor, fears the 1,000 square metre renovation will take longer than hoped.

"It is a four month project, but because of the lockdown, I don’t know how long it will take," he says. With almost all industry closed and the entire country under 24-hour curfew, the builders have been struggling to acquire essential materials (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

Massaad has a master’s degree and nine years of experience. The assistant head nurse earns the equivalent of around $230 per month as a result of Lebanon’s runaway currency depreciation and collapsing economy. Construction labourers earn between $6 and $9 per day.

Putting their all into the pandemic response and the explosion rebuild for a pittance is taking its toll on those working at St George’s and across Lebanon. "We can’t continue like this as a country," says Massaad. "We’re living day-to-day, I don’t know what will happen next and we are all very worried about our mental health" (MEE/Elizabeth Fitt)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].