How Turkey’s endangered mountain gazelle was saved from extinction

Behind a heavily armoured Turkish military vehicle on patrol near the Syrian border, mountain gazelles give chase in a spectacular display, reaching speeds as fast as 80km per hour.

Among the spectators is the Turkish scientist and conservationist Professor Yasar Ergun - a man largely responsible for the survival of the species in Turkey’s southern Hatay province.

“The males are trying to outrun each other in order to claim victory and become the alpha this season,” he says, sticking his hand out in the direction of a herd of around 20 females, 50 metres away, some grazing, some watching the performance.

“The winner gets to pass its genes on to the entire female herd this year,” Ergun says with a palpable sense of satisfaction.

Once severely endangered, now, the iconic mountain gazelle, also known as Gazella gazella, thrives again in this corner of Turkey. The cast of characters responsible for its success story includes Ergun and his teams, locals in the nearby town of Kirikhan, and - through an unexpected by-product of regional tensions - the Turkish military.

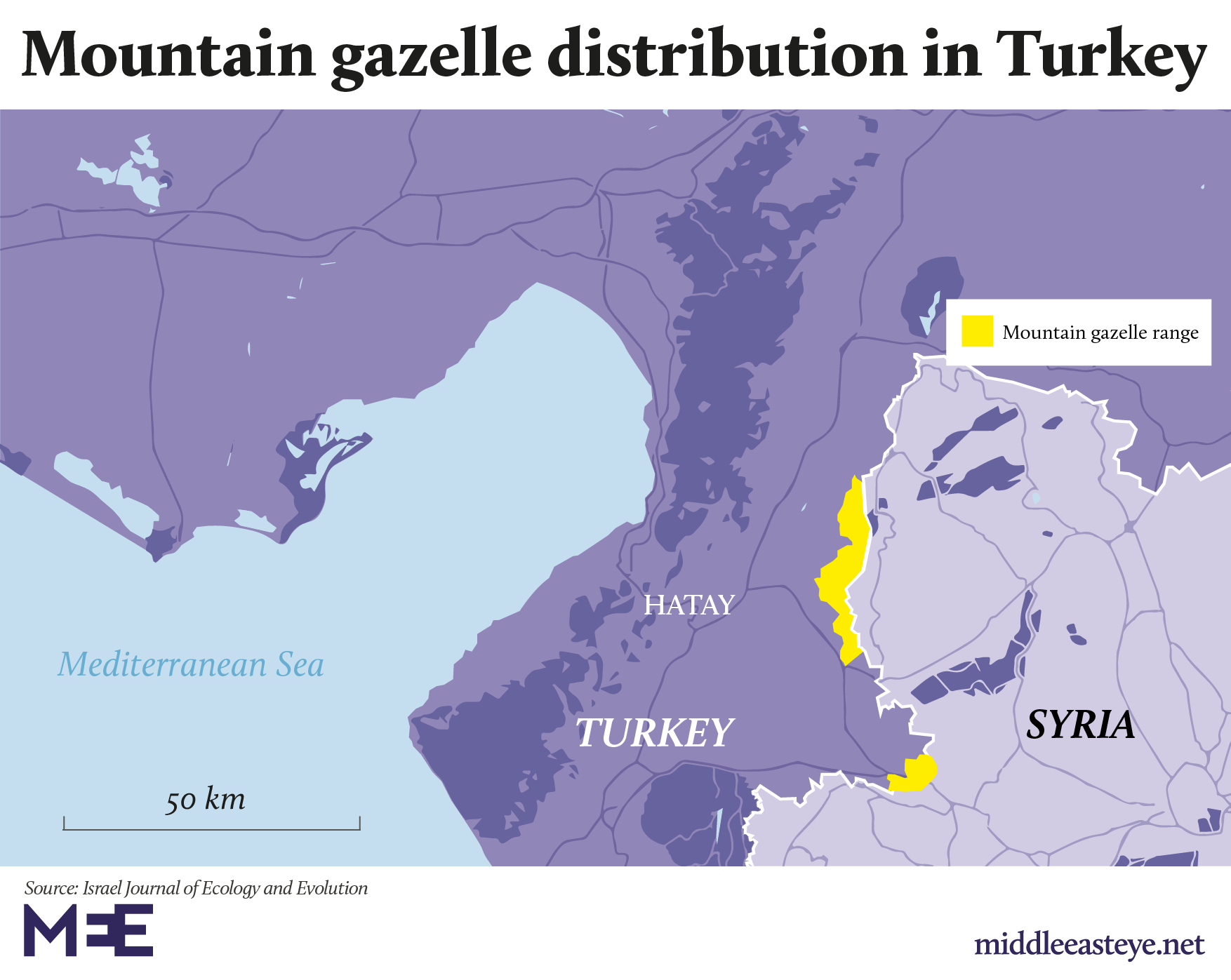

According to a survey conducted by Turkish officials in late 2020, there are at least a thousand mountain gazelles in a reserve covering 13,288 hectares near the Syrian border, which was declared a protected area by presidential decree in 2019.

Explaining his concerns about the fragility of biodiversity in the region, Ergun says hunting by humans and habitat encroachment had left gazelle numbers at around a hundred as recently as 2008.

Gazelles have long lived in this area of southern Turkey - even making an appearance in Roman mosaics discovered in the region. However, until its re-discovery by Ergun in 2008, the mountain gazelle species had been considered almost extinct.

Together with his conservationist friend Abdullah Ogunc, Ergun, who teaches at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Hatay’s Mustafa Kemal University, moved to ensure the gazelles’ survival.

Conservation efforts

Found in small clusters across the western Levant region, Gazella gazella is also classified as endangered in Israel and the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories.

As of 2015, the species has suffered a dramatic drop in population in Israel, which makes the recent recovery of the Turkish population all the more remarkable.

The animals have been victims of urbanisation, as humans build towns and farms on territory traditionally inhabited by gazelles, depriving the animals of grazing land, as well as safe breeding spots. In Turkey, poachers have also threatened the stability of gazelle numbers in the past.

Addressing those threats forms the core of Ergun and his colleagues’ strategy to protect the gazelles.

One of the first things the scientists did was to classify the gazelles found in Hatay in order to distinguish them from related species in neighbouring regions. This was done through DNA testing overseen by the Turkish mammalogist Professor Tolga Kankilic.

The findings helped Ergun establish that the Hatay variety of gazelle was of the species Gazella gazella, and not Gazella subgutturosa, which is mainly found in nearby Sanliurfa province and has a larger population.

While both species look similar to the untrained eye, the former differs from the latter in that it has a more slender neck and leg, and prefers to live in more hilly terrain.

By confirming that the animals in Hatay province were of a more endangered species of gazelle, Ergun was able to galvanise fellow scientists, government officials, and locals to join his campaign to prevent the mountain gazelle’s extinction.

Together with his team of conservationists, Ergun set about creating as much media buzz as possible regarding his discovery, successfully publishing a number of articles, appearing on talk shows, and even getting Turkey’s public broadcaster TRT to shoot a two-part documentary on the animals in 2010.

He also gave tours of the gazelle’s natural habitat to local educators, students, officials, and representatives of international and local animal welfare groups, such as the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), which participated in the campaign by disbursing funds, and the Hatay Nature Protection Association (Takoder), of which Ergun and Abdullah Ogunc are leading members.

These awareness drives paved the way for a series of projects that have had practical implications for the gazelle’s survival.

As part of one such project, volunteers have set up the first watering station to help the mountain gazelles through dry summers. Designed to mimic natural springs, so as not to put off the animals, water pipes are laid underground where they feed water through to a stone pool.

“It took them two years to get used to the first waterbed, but now it’s their routine,” Ergun says.

Local beliefs

In a separate Ministry of Agriculture and Forestries project, locals in Hatay have been recruited to watch over the gazelles at a breeding station.

This facility has large fenced-off areas where the gazelles can gather safely, free from hunters and curious locals, who may feed or play with the animals, creating dependency on human populations, although the station accepts day visitors under supervision.

Such endeavours tap into local folk beliefs about the sacredness of the gazelle and the necessity to protect them.

Huseyin Dinler, who is one of four keepers at the breeding station, recounts traditions passed down through generations, which hold that misfortune befalls those who kill the gazelle.

“I’ve seen with my own eyes that whoever shoots a gazelle gets punished,” he says.

“Someone I know got a bad disease…someone else I know had (a rifle) blow up in his hand while hunting.”

Accounts of these misfortunes stem from generations-old folk stories involving a holy man, Gazelle Baba, who is believed to buried in or around a shrine near the Syrian border. The man, who worked as a shepherd, got his name from a legend, which says wild gazelle would approach him offering him their milk in a manner not in their nature as untamed animals.

The local relationship with the animals stretches back centuries to at least the Roman era. A discovery of a Roman artefact in Dinler’s own land led to an excavation that uncovered mosaics and other relics featuring images of the gazelle.

A sense of sacrilege when it comes to harming the gazelles also extends to some of the hunters themselves.

Describing a belief associated with the gazelles at a local rifle shop, Dogan Ozturk says that if you point a gun at a gazelle, it bends its neck, saying in a mesmerising tone: “Please, don’t shoot me.”

According to Ozturk, hunters who targeted the gazelles would also “definitely get beaten by the locals”.

Ergun and his colleagues credit these traditions with helping foster local support for their campaign to restore the mountain gazelle population and have provided locals like Dinler with equipment, such as walkie-talkies and raincoats, as well as logistical support.

Military zone

While such beliefs have indeed helped efforts to conserve the mountain gazelle, the most practical support for the project has come from the Turkish military build-up on the Syrian border

As war has raged in neighbouring Syria, the Turkish army has carried out multiple incursions into the country, setting up a closed military zone on its side of the border.

The restricted area in Hatay, which took on military signifcance in 2018 during Operation Olive Branch, means poachers entering the area must contend with Turkish soldiers and risk fines issued by the military if caught.

With restrictions on who can enter their natural habitat, the gazelles have been afforded the ability to live their lives largely free of human interference.

“If this wasn’t a military zone, there wouldn’t be a hundred surviving gazelles here,” says a military officer, who does not give his name because he is unauthorised to speak on the record.

'They [gazelles] don’t run away from us. They are thin, graceful, fragile, and clean. I feel they are sacred'

- Turkish military officer

In a comment that reflects the strength of local feeling towards the gazelle, he also says: “They [gazelles] don’t run away from us. They are thin, graceful, fragile, and clean. I feel they are sacred.”

The aggregated effect of the military zone, scientist-led conservation efforts, and local support has been the recovery and survival of the mountain gazelle.

Still, Professor Ergun knows the dangers of complacency. While hunting is on the wane, threats to the gazelle’s habitat remain in the form of agricultural encroachment and mining interests.

Residual pesticides and unauthorised farming were cited as the biggest threats to the gazelles in a 2017 memorandum issued by the Turkish Ministry of Forestry and Water Affairs, as part of its Hatay Mountain Gazelles Species Action Plan.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, an official from Turkey’s Directorate of Nature Conservation and National Parks (DKMP) tells MEE: “Hunting is no longer a serious threat...our biggest worry now is greedy farmers.”

Taking on big business has been a comparatively easier task.

In autumn 2020, a company lobbied for the right to build a stone quarry and a cement factory inside Hatay’s gazelle reserve.

“In 14 years, we’ve only been in court once [to protect the gazelles] and this was it,” Ergun says.

With years of research behind him confirming the importance of the mountain gazelles, the court ruled in favour of the conservationists and plans for the commercial project were halted.

“Had we not created our strategy based on evidence and recorded the species to prove its existence in this region, it would be very difficult for us to win these big cases,” the professor says.

“We won thanks to science.”

Journalist Giuseppe Didonna contributed to this report. Didonna has been covering news from Istanbul since 2014 as a reporter for the Italian news agency AGI and as a producer for the Italian state news channel Rai News.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].