'Digital Suez': How the internet flows through Egypt - and why Google could change the Middle East

There are only a few historically strategic transit points around the Mediterranean Sea: the Strait of Gibraltar, the Bosphorus, and the Suez Canal.

While the Suez Canal has been a jewel in Egypt’s crown since 1869, netting the country some $5.6bn in revenues in 2020, it accounts for just eight percent of world cargo shipments.

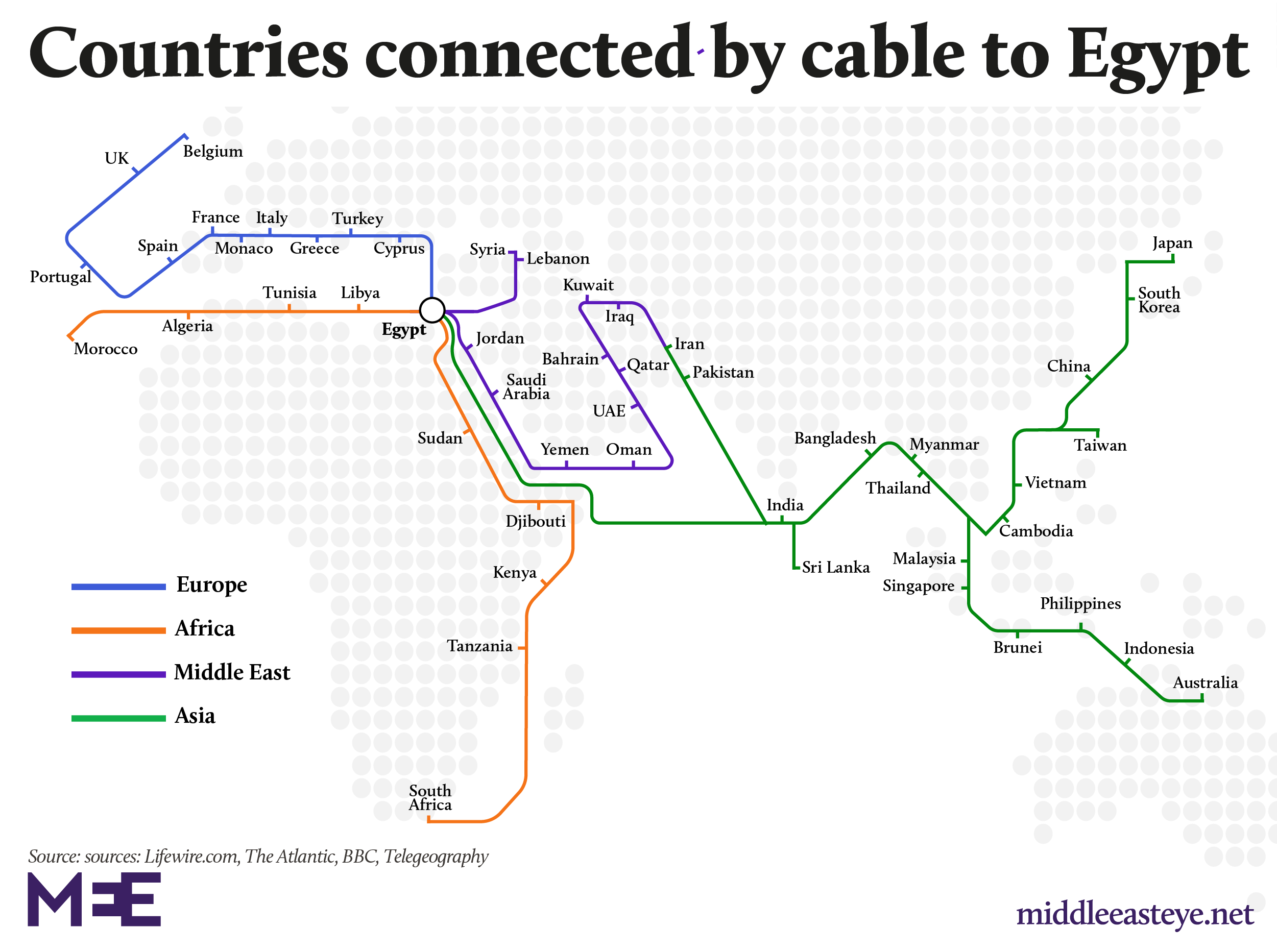

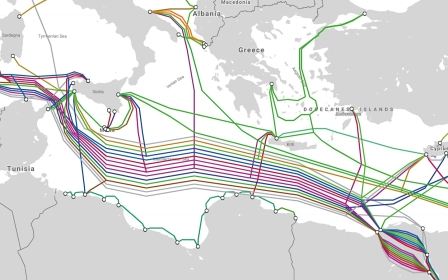

But Egypt’s location as a fibre optic cable hub, linking Europe, Africa, the Middle East and Asia, means up to 30 percent of the global population’s internet connectivity transits through the country.

“If you want to route cables between Europe and the Middle East to India, where’s the easiest way to go? It is via Egypt, as there’s the least amount of land to cross,” says Alan Mauldin, research director at telecommunications research firm TeleGeography in Washington DC.

Egypt, through its state-owned monopoly Telecom Egypt (TE), has successfully capitalised on its position to entice cable operators to transit the country.

“It is one of Egypt’s trump cards, like the Pyramids, which never goes out of fashion. They are used to making business out of transit and tourism, but now they’re doing it with data. It is a digital Suez canal, which trades on its geopolitical position,” Hugh Miles, founder of Arab Digest, in Cairo, told Middle East Eye.

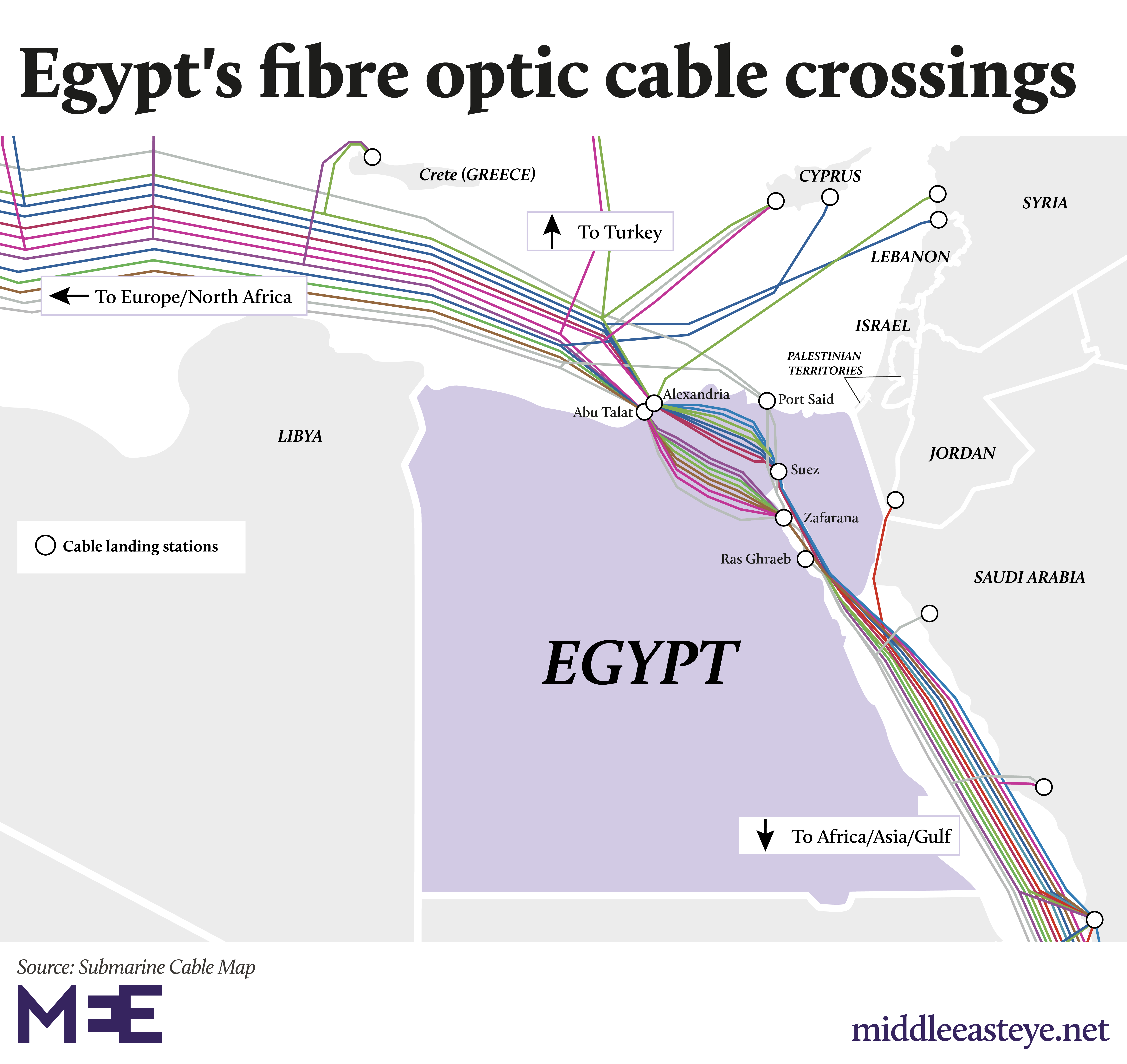

There are 10 cable landing stations on Egypt’s Mediterranean and Red Sea coastlines, and some 15 terrestrial crossing routes across the country, of which 10 are operated by the Egyptian telecom giant, spanning a region stretching from the Mediterranean as far as Singapore, according to TE.

Its centrality to global connectivity - TE estimates that 17 percent of internet traffic flows through Egypt while some analysts suggest it could be as high as 30 percent, connecting between 1.3bn and 2.3bn people - has led to Egypt being considered a choke point.

“Internally we call it the Red Sea bottleneck, as you have a dozen plus cables linking Asia to Europe, and Africa to Europe. It is essentially a toll one has to pay to pass through the Suez area, which is busy due to shipping and technology lanes,” says Guy Zibi, founder of South African market research firm Xalam Analytics.

The monopoly has provoked the ire of the cable industry and global internet players, with reports that Egypt is charging 50 percent more than other transit cable routes.

“There is a fee they charge for capacity, which was lowered a few years ago. There is constant pressure to lower it more,” says Mauldin.

It is not just price that has the industry concerned. “The challenge with Egypt is if there is a break, or some kind of regulatory uncertainty, that blocks traffic, as it would choke off a substantial part of internet traffic around the world,” says Zibi.

Mauldin says it is in Egypt’s interest that there are no disruptions to global internet traffic but what the industry wants is more diversity. “You are forced to go through Egypt, which is partly why there’s a need to create alternative paths and for competition. The best way to improve international connectivity is to simply build more cable paths.”

A cable contender?

There has been a flurry of new cables laid across Egypt in the past few years, including the Pakistan East Africa Cable Express (PEACE) network, 2Africa, and the Cape Town to Cairo network.

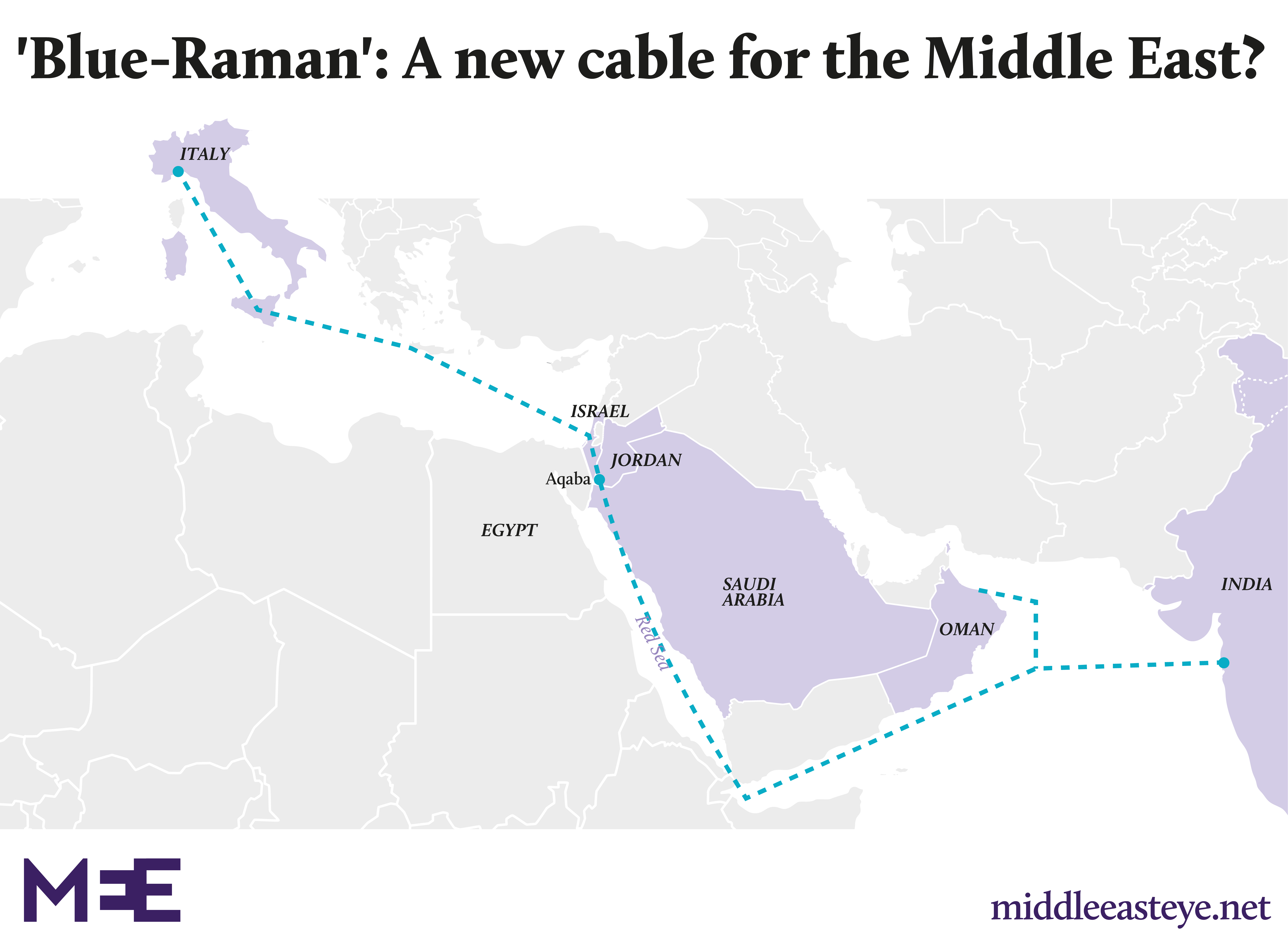

But now a new route between India and Italy reportedly being planned by Google - though still unconfirmed - risks undermining Egypt’s stranglehold.

According to reports, the $400m “Blue-Raman” network would consist of two linked cables. The “Blue” cable would run from Genoa in Italy to Israel, and then bypass the Suez area via a terrestrial cable running to the Jordanian port of Aqaba. The “Raman” cable would run from Aqaba through Saudi Arabia and Oman and across the India Ocean to Mumbai.

“Google, Facebook, the hyper-scale providers, are all looking to have more control of their own traffic rather than purchasing capacity on existing cables. Nothing is cheaper than to own your own capacity,” says Zibi.

If constructed, Blue-Raman would be a geopolitical game changer for the region’s cable networks. Israel currently has no link to the Middle East, relying on cables from Europe to Tel Aviv and Haifa.

Furore in Egypt

Blue-Raman has already caused a furore in Egypt. Osama Kamal, an Egyptian TV host, was suspended in December by the Supreme Council for Media Regulation after accusing the authorities of corruption and of losing the country’s position as a fibre cable hub.

“It was a major scandal, with the host suspended, and we don’t know what happened to him during that time,” said an Egyptian academic working on surveillance issues.

Blue-Raman would not, however, seriously impact Egypt’s cable-transiting dominance, or undermine the EGP2.9bn ($185.3m) that TE makes a year from fibre cable services.

“It is not about taking traffic from Egypt, but diversifying away from TE without getting rid of TE,” says Zibi.

Google has yet to make any official comment on Blue-Raman and told Middle East Eye: "We don't comment on market speculation".

This may be due in part to expectations of a normalisation agreement between Saudi Arabia and Israel following the Abraham Accords, inked just months before Blue-Raman made headlines, failing to materialise.

“Blue-Raman totally hinges on regional politics. Of course it’s a great idea and makes perfect business sense and that’s why Google wants to do it, but it overlooks the small issue of Middle Eastern politics - projects don’t often go as planned, due to wars, enmities, and other regional problems,” says Miles.

Cabling normalisation

The speculation is that Saudi Arabia’s King Salman is opposed to recognising Israel, which would make the Google cable’s prospects dependent on Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman becoming monarch. One attraction of such a deal for the Saudis would be access to Israeli IT and surveillance technology, which has been a particular draw for the UAE.

Such technology, a fibre optic cable with ample capacity, and a peace deal would bolster the viability of the crown prince’s Vision 2030 ambitions, which include the $500bn Neom project that borders the Red Sea, and the recently announced $200bn project, The Line.

“Blue-Raman fits into a bigger picture of unity in the region. Neom is supposed to be the heart of this, of four countries [Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan and Israel] all coming together and working together. You can be sure the Saudis want to be networked on this big cable,” says Miles.

Google’s plan to establish a new Google Cloud region in Saudi Arabia, which the kingdom has sought as part of its diversification plans to digitalise the economy, is also a motivation.

“The data centre would link to Blue-Raman, and is probably one of the things that helped justify the investment,” says Zibi.

Google’s new deal

While Google has been silent about Blue-Raman, in January the company signed a deal with TE for cable capacity through Egypt.

“The deal isn’t necessarily an alternative to the Blue-Raman cable because the new plan still doesn’t solve the bottleneck issue,” says Sarah Smierciak, an independent political economy analyst in Cairo.

Google would link up to the TE North cable that runs from southern France to the Red Sea.

“This is the same general route that most cables take, so it doesn’t fix the problem of over-reliance on Egypt and the country’s quasi-monopoly,” added Smierciak.

TE collected 10 percent of its earnings from cables in 2019, and looks set to remain a contender even if Blue-Raman is started.

Any cable deal through the country benefits Egypt’s military industrial complex.

“The military almost certainly owns the land where the new cables for the Google deal will be laid,” Smierciak says.

A 2016 presidential decree placed the land straddling national roads under control of the Ministry of Defence. “Any revenues from commercial deals on that land will go to the military's coffers. The Google deal will be a boon for TE and the military will also enjoy substantial rents,” she added.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].