Tariq al-Bishri: A legacy of resolving Egypt's tensions

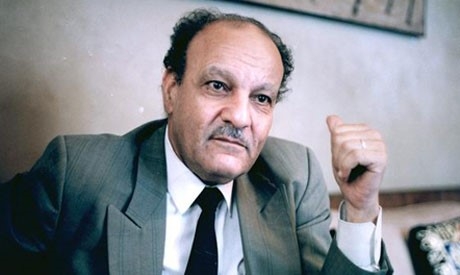

Tariq al-Bishri, Egyptian judge, historian, legal theorist and public intellectual, died, a victim of Covid-19, last Friday at the age of 87.

A prolific author, al-Bishri leaves behind an immense intellectual and political legacy, and his passing represents the end of the post-colonial era. He is the grandson of Salim al-Bishri, who twice served as Shaykh al-Azhar, first from 1900-04 and second from 1909-16, and son of Abdel Fattah al-Bishri, who served as president of the Egyptian Court of Appeals (Cour de Cassation), then the most prestigious court in Egypt.

Al-Bishri grew up firmly ensconced in Egypt’s most prestigious religious and modernising institutions. His intellectual, judicial and political career is best understood as an attempt to resolve the tensions between these two currents of Egyptian society through the democratisation of the Egyptian state.

From left to Islamism

Upon his graduation from the Faculty of Law of Cairo University in 1953, al-Bishri joined the newly created Majlis al-Dawla (Conseil d’Etat). Inspired by the French institution, the Egyptian version functioned as a supreme administrative court intended primarily to resolve disputes between and among various agencies of the Egyptian state, but it also provided a forum for Egyptian citizens to complain of unlawful treatment at the hands of the Egyptian bureaucracy.

Al-Bishri's early politics were leftist in orientation, which included a view of elites as charged with the social role of transforming society to bring it into modernity

He played a particularly important role in strengthening this institution in the 1980s and 1990s, when he authored an important decision in 1992 striking down the validity of military trials for civilian defendants. Because this was an administrative decision, however, it was of little effect as the Mubarak government quickly changed the law to provide the necessary authority to continue with the practice.

Al-Bishri retired from the Conseil d’Etat in 1998 as first council of the Conseil d’Etat and president of the General Committee for Legal Opinions and Law-Making (al-jamʿiyya al-ʿumumiyya li’l-fatwa wa’l-tashriʿ).

His early politics were leftist in orientation, which included a view of elites as charged with the social role of transforming society to bring it into modernity. After the disastrous defeat of 1967, he abandoned this transformative conception of the role of the elite in politics. He instead adopted a more localist understanding of the political role in which the elite served as a source of renewal for the vitality of those local values that could bring about the desired change.

Although often understood as a moderate Islamist, al-Bishri’s legacy towards political Islam is better understood from the perspective of his shift from a leftist theory of social change to a theory of social change that was rooted in the organic values of society itself. Accordingly, Egypt’s only realistic path for democratisation inevitably had to go through Islam, insofar as Islam - and Islamic law - represented the common cultural inheritance of all Egyptians, whether or not Muslim.

His revised conception regarding the place of Islam in Egyptian democratic transformation was made explicit in the 1980 reprint of his 1972 monograph titled:The Political Movement in Egypt, 1945-1952. In its original printing, he played down the role of the Muslim Brotherhood in paving the way for the 1952 revolution, giving more credit to the activities of Egyptian communist and socialist organisations.

In the 1980 reprint, however, he revised his opinion, and argued in a lengthy new introduction to the book, that in fact, it was the Muslim Brothers, and not the Egyptian left, who were the true bearers of democracy in Egypt.

An Egyptian nationalist

Throughout his intellectual life, al-Bishri was an Egyptian nationalist - not the exclusionary, chauvinistic faux-nationalism of post-2013 coup Egypt, but the nationalism of Rifaah Rafi al-Tahtawi, a 19th-century Egyptian intellectual, that was based on love of one’s home, the sincere desire to seek its welfare, and a welcome spirit to all those willing to cooperate in that venture, without demonising those outside the national community.

His 1980 book titled Muslims and Christians in the Framework of National Unity is a testament to his nationalism. He began writing this book in the wake of the 1967 catastrophe as a kind of resistance to the despair that defeat imposed on the national project.

Its goal was to tell a story of a coherent Egyptian national community that transcended sectarian divisions, one that was united in building a state that would achieve three goals: Egyptianisation of the state, by which he meant that all offices of the state and the military would be open to all Egyptians; liberation from foreign domination; and, finally, liberation from the arbitrary rule of the state, through democratisation.

The first goal was gradually achieved throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, first by Muhammad Ali and his successors, as Egyptians were gradually able to find their way into most ranks of the state’s civilian and military elite, and then by the Free Officers’ Revolution of 1952, which completed that task.

The second goal - freedom from foreign domination - was also achieved by the Free Officers, but at a high price: the establishment of an authoritarian, bureaucratic state that stood in the way of achieving the final goal of the Egyptian national movement: liberation from arbitrary rule.

Endorsing disobedience

As a political theorist, al-Bishri was most concerned with how the authoritarian, bureaucratic rule ushered in by the Free Officers had retarded Egypt’s political development. He was sympathetic to the political role of Islam in modern Egyptian society because he saw it as the best way to establish a more democratic, bottom-up political order that could resist the authoritarian evolution of the Egyptian state.

After his retirement from the Conseil d’Etat in 1998, he became more outspoken in his opposition to the authoritarianism, corruption and personalisation of rule that had become entrenched during the Mubarak regime, publishing a work in 2006 with the title Egypt: Between Civil Disobedience and Disintegration, in which he endorsed massive civil disobedience as a strategy to confront authoritarianism and to democratise the state.

There can be no doubt that the 2013 coup for al-Bishri must have been as much a worldview shattering moment as the 1967 defeat

In the wake of Mubarak’s resignation from the presidency after the 25th January popular uprising , al-Bishri chaired a committee of Egyptian lawyers tasked with amending the 1971 Constitution to permit a meaningful democratic transition to take place. When the limited character of these amendments were disclosed, however, it led to the first significant breakdown of the revolutionary coalition.

Much to al-Bishri’s chagrin, the military intervened, and instead of submitting the proposed amendments for approval in a referendum, it submitted the amendments as part of a new, skeletal constitution that the military itself promulgated. While perhaps not evident at the time, the military’s assumption of constitutional authority in the March 2011 referendum augured the misfortune that would soon visit the hopes and aspirations of Egypt’s revolutionaries, when Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, then minister of defense, with the backing of Egypt’s military and police, seized power in a bloody coup.

Despite his criticism of the Muslim Brotherhood’s performance in government after Mohammed Morsi’s election in 2012, al-Bishri did not shy away from declaring what happened in the summer of 2013 at the hands of Sisi to be a coup against a democratically elected government.

A shattering moment

There can be no doubt that for al-Bishri the 2013 coup must have been as much a worldview shattering moment as the 1967 defeat, perhaps even more so because it came at the hands of the Egyptian people themselves. Al-Bishri had a strangely optimistic, even teleological, view of history as progressive, and to that extent, he never ceased being a leftist.

The brutal authoritarianism of the Sisi regime left no space for al-Bishri to express his views publicly

Unfortunately, we may never know how al-Bishri - the political thinker - came to understand the coup and its meaning for modern Egyptian history: the brutal authoritarianism of the Sisi regime left no space for al-Bishri to express his views publicly. Perhaps they will be revealed in the fullness of time, if, as I suspect he did, leave for later generations unpublished writings that merely await a more propitious moment for them to be revealed.

But until then, we are left to speculate about his thoughts on the restoration of a vicious authoritarianism in Egypt unprecedented in scale. No doubt Bishri left this world to meet his maker mourning what could have been. Today, however, we honor Bishri’s life of work for the progress of Egypt, and hope that someday, sooner rather than later, Egyptians achieve his greatest hope - liberation from the arbitrary rule of the state.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].