Syria war: Will the Arab League welcome back Assad?

Syria has been excluded from the Arab League for nearly a decade, but that may be about to change. Last week, the United Arab Emirates called for the war-torn country to be restored to the organisation it helped found in 1945, echoing similar calls by Iraq in January.

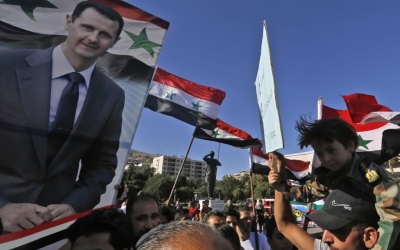

Some of the League’s agencies have already restarted operations in Damascus. This seems a long way from November 2011, when an unprecedented 18 out of 22 Arab League members voted to suspend President Bashar al-Assad amid his brutal crackdown that began the Syrian civil war. Yet Assad has survived, and events elsewhere have prompted a rethink by the Arab states that once opposed him.

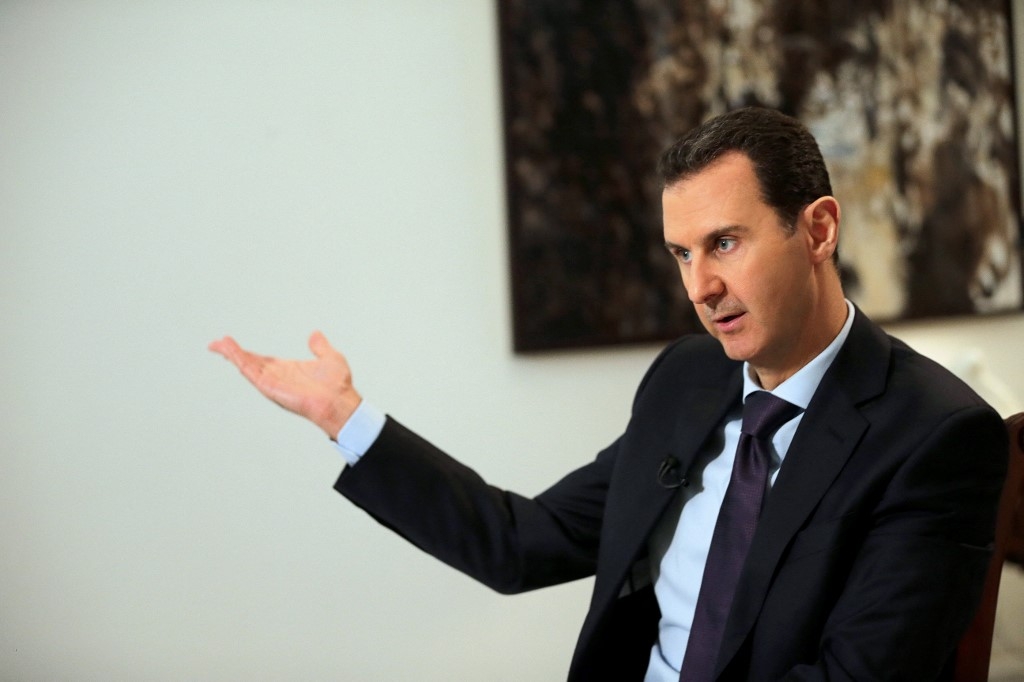

Whether or not Syria is returned to the Arab League, one thing is clear: it will not likely have anything to do with a change in Assad's behaviour

It might seem odd that Assad would even want to rejoin the League, given that it is largely powerless and the majority of its members condemned him. Yet, a return to the Arab fold would bring benefits. At home, the Assad regime has long relied on Arab nationalist rhetoric, and returning to the League might bolster its legitimacy among some loyalists. Abroad, a return would help break Assad’s postwar international isolation, opening the way for other reconciliations.

Most importantly, Assad and his Russian allies believe restoration to the Arab League could open the door to much-needed reconstruction funds from the Gulf, which the floundering Syrian economy desperately needs. Indeed, it is no coincidence that the talk of restoring Assad has come as part of a diplomacy drive by Russia in the Gulf.

So what has prompted the shift in position from Arab League members? Assad was never completely isolated, with neighbours Lebanon and Iraq refusing to vote for the 2011 suspension. As fellow friends of Iran, relations remained close throughout the civil war.

Another early outlier was Algeria. It reluctantly approved the suspension, but never cut ties with Damascus. A military-led regime that fought its own long civil war with Islamists, Algiers has long had sympathies with Assad and has frequently argued to end his Arab isolation. This position has not wavered, despite a recent change in leadership after popular protests.

Shifting stances

In contrast, two significant players have changed their stance. After Egypt’s 2011 revolution and the election of a Muslim Brotherhood government, the state was a vocal Assad critic. However, the military regime that toppled it in a coup in 2013 has been closer to Damascus, seeing Assad as a fellow autocrat struggling against Islamist “terrorism”.

The UAE has also become more accommodating. While it was never that adamantly against Syria, permitting regime members - including Assad’s immediate family - to use the Emirates as a safe haven, it has become a leading advocate for reconciliation, even reopening its Syria embassy in late 2018.

Like Egypt, the UAE is staunchly anti-Muslim Brotherhood, a group that was well-represented among Syria’s opposition. Moreover, both Cairo and Abu Dhabi are keen to contain the growing regional role of Turkey, itself a strong supporter of the Brotherhood, and are wary of its advances into northern Syria. Arab League reconciliation with Assad would help to outflank Ankara.

On the other side of the debate are Qatar and Saudi Arabia, which are most reluctant to welcome Syria’s Arab League return. Doha is the most forthright, aligned with Turkey in its continued condemnation of Assad. Yet, while in 2011 it was a major player in the Arab League, leading the charge to suspend Syria and even threatening Algeria if it didn’t conform, today it is more marginal.

Though the blockade by its Gulf neighbours was recently lifted, Doha remains weaker than in 2011 and, were the other Arab states to vote to readmit Assad, it would struggle to prevent it.

Saudi caution

Saudi Arabia is a more significant obstacle, but also more ambivalent. Like its allies Egypt and the UAE, it is fearful of both Turkish expansion and the Muslim Brotherhood, and has flirted with the idea of reconciling with Assad. It approved close ally Bahrain’s reopening of its Syria embassy in 2018, which at the time many believed was a trial balloon for Riyadh to do the same.

Likewise, last year, it quietly allowed Syrian trucks loaded with goods to pass into Saudi Arabia, a shift from its wartime restrictions, indicating a possible thaw. This was strengthened at a recent Russian-Saudi press conference, when both countries' foreign ministers spoke of Syria’s return to “the Arab family”.

And yet, Riyadh remains cautious. More than the UAE and Egypt, it is wary of its rival Iran’s enhanced presence in Syria. While reconciliation with Damascus could allow it to dilute Tehran’s role somewhat, this would still only be marginal and could ultimately reward its enemy.

The other major roadblock is the United States and its Caesar sanctions regime, which punishes any business or individual who deals with sanctioned Syrians. In calling for Assad’s return to the Arab League, the UAE acknowledged that these sanctions “make the matter difficult”. The unknown for Abu Dhabi and the other Arab states is how zealous the new Biden administration will be in maintaining these Trump-era sanctions - even though they originated in Congress, not the White House.

Geopolitical alliances

With attention on the Covid-19 pandemic at home, and with US President Joe Biden’s regional priorities seemingly on Iran, not Syria, it is possible that the UAE and others may find a way to gradually reintegrate Assad without provoking opposition from Washington. This will certainly be the UAE’s, Russia’s and Assad’s hope.

But whether or not Syria is returned to the Arab League, one thing is clear: it will not likely have anything to do with a change in Assad’s behaviour. All members seem driven by events outside of Syria: how embracing Assad or keeping him isolated will impact their wider geopolitical alliances and rivalries.

Realpolitik, rather than principle, will ultimately determine Assad’s Arab League fate.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].