Yemen: Fishermen find valuable 'whale vomit' and become rich overnight

Life as a fisherman in Yemen has become near-impossible since the outbreak of war six years ago.

Setting out onto the waters can be hazardous while warring parties are on edge, and many of Yemen’s seas are restricted areas, cutting off thousands of Yemenis’ source of livelihood.

In southern Aden province, restrictions are looser, drawing displaced fishermen from more dangerous coasts like Hodeidah. But work is scarce, as are equipment and boats, and more often than not Yemenis who once had their own vessels now join larger fishing parties and must share the spoils with several others - as well as the costs.

But one day in February, a group of fishermen from the village of al-Khaisah, including some displaced from Hodeidah, hit the seas for what would prove to be a most profitable voyage, one that would transform their lives.

They came across a giant sperm whale corpse, which contained a mammoth chunk of ambergris, a rare substance known as “floating gold” or “treasure of the sea”.

“When the fishermen passed by a large dead fish, a fisherman displaced from Hodeidah shouted to other colleagues, as he recognised it as a sperm whale,” Abdulrahman*, one of the fishermen who retrieved the whale, told Middle East Eye.

“Hodeidah’s fishermen have experience in recognising sperm whales from others. We had passed by that same dead fish more than once, and we didn’t give it any attention as the sea is full of dead fish. But the displaced fisherman's experience made the difference.”

Ambergris is a solid mass of material consumed by sperm whales that grows in its intestines over several years. Sometimes known as “whale vomit”, it is thought to occasionally be regurgitated but more often passed through the digestive system.

Though not particularly pleasant, the curious substance is incredibly valuable: an oil is extracted from ambergris to make perfume last longer and is used for only the most expensive odours.

Ambergris: Treasure of the sea

+ Show - HideAn odd, pungent, rock-like substance, for centuries ambergris was one of nature’s greatest mysteries.

Though humans have used it for around 1,000 years, its origin only became known in the 19th century, when whalers realised it came from one source: sperm whales.

Ambergris is developed in the sperm whale’s intestines, the binding together of indigestible parts of squid and cuttlefish that become a solid mass over several years.

Though it is commonly referred to as “whale vomit”, scientists believe that most ambergris found floating in the sea or washed up on the shore is in fact passed through with faecal matter.

However, it is thought that some sperm whales also regurgitate it in death.

The Aden fishermen found their lump inside a whale’s intestines, but less than five percent of dead sperm whales contain ambergris.

When first extracted, ambergris is said to have an overpowering and repugnant smell, which mellows into a musk far sweeter as it dries out.

In 1895, the New York Times described the odour as “new-mown hay, the damp woodsy fragrance of a fern-copse, and the faintest possible perfume of the violet”.

Quite apart from its scent, the oil extracted from ambergris, ambrein, is used by top perfumers to help fix perfume to human skin and make it last longer. It is used by top-end perfume houses, such as Chanel and Lanvin.

Ambergris’ use has not always been restricted to perfume, however.

Centuries ago, Arabs employed specially trained camels to seek it, and used ambergris in medicines for the heart, brain and senses.

They also used it as an aphrodisiac, a property Nostradamus and many others throughout history have believed it had.

Meanwhile, Charles II of England ate ambergris with eggs for breakfast.

Abdulrahman had never found ambergris in all his years fishing. He said maybe he’d passed by some floating in the water, but never recognised it, as he was only on the lookout for fish to catch.

“The displaced fisherman was in a boat with other fishermen, and more were in another boat nearby, but they couldn’t bring the dead whale to the coast alone,” Abdulrahman recalls.

“So they asked nine boats to help them and they brought the dead whale to a beach off Aden's Shamsan Mountain,” he added.

By noon that day, the fishermen began slicing open the whale’s carcass. They found blubber, guts and bone, but the precious ambergris was nowhere to be seen. Until there it was: life-changing wealth.

'More than 100 fishermen participated in bringing the whale to the coast, cutting it open and then guarding the ambergris and selling it'

- Abdulrahman*, fisherman

“More than 100 fishermen participated in bringing the whale to the coast, cutting it open and then guarding the ambergris and selling it,” Abdulrahman said.

To avoid any disputes, the fishermen agreed on a percentage for each man before selling the ambergris. They then sold it for 1.3bn Yemeni rials, which is worth about $1.5 million on the street.

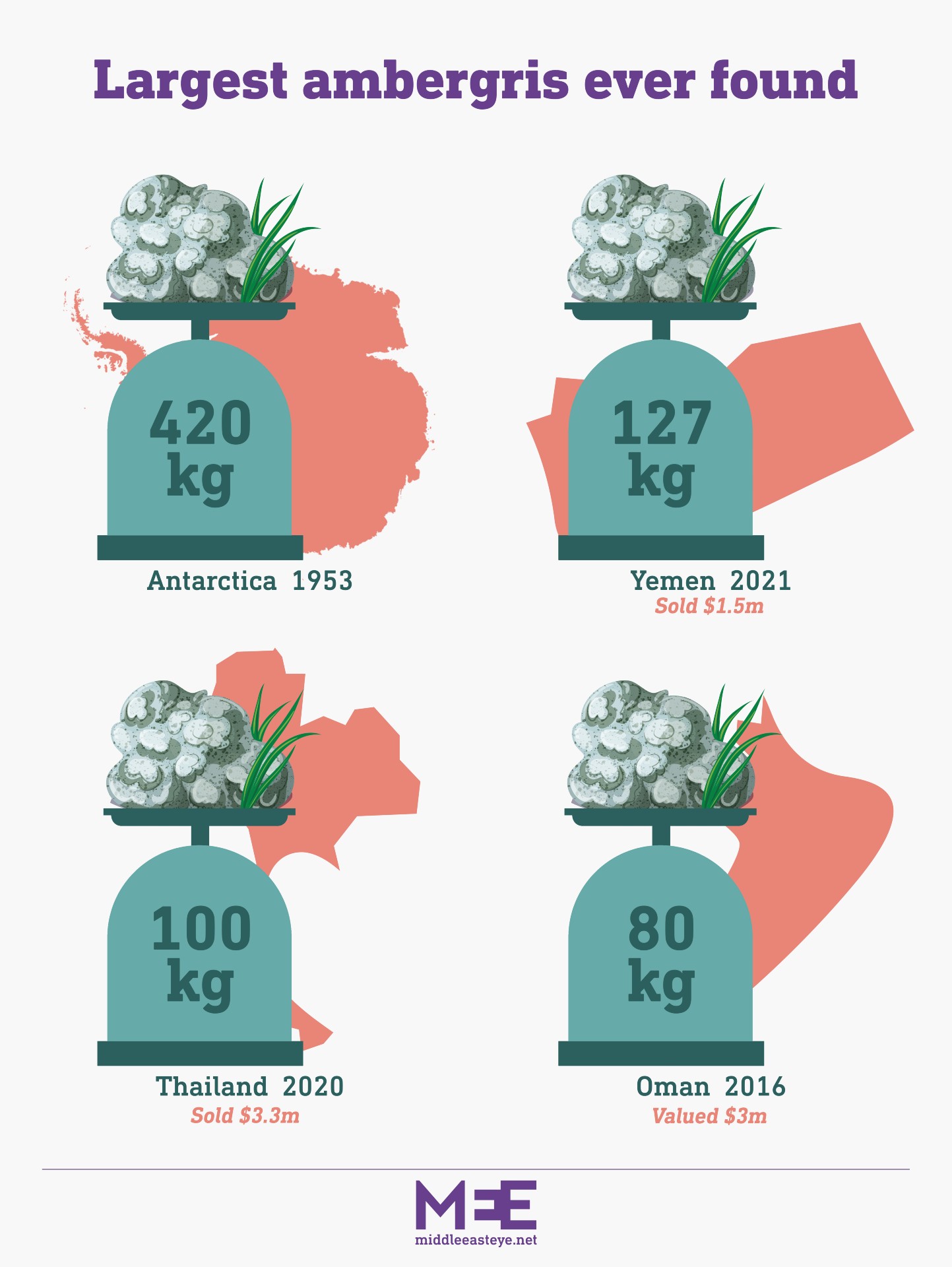

The ambergris weighed in at 127kg and the fishermen sold it to a trader from the United Arab of Emirates, Abdulrahman acting as the broker.

“Every family in al-Khaisah was filled with happiness, because all of them got some money from the sale of the ambergris,” Abdulrahman said. “Some fishermen got 30 million, some others less or more, and even the guards got 250,000 rials each. Each person got money based on his role.”

Sharing the spoils

At such a tough period of Yemen’s history, where two-thirds of the country’s 30 million population are reliant on humanitarian aid, and at least 230,000 people have been killed in the conflict, good news is a rarity.

But the ambergris discovery will transform the lives of the people of al-Khaisah, a village of around 1,000 families in the al-Buraiqa district south of Aden city.

“The fishermen gave some money to needy people in al-Khaisah village in an act of charity for the sake of God. Everything was good and the charity made the residents of the village happier,” Abdulrahman said.

According to Abdulrahman, most of the fishermen who retrieved the whale don’t have their own boats and struggle to earn enough to provide for their families.

“Thirty million Yemeni rials is enough these days to build a home and marry, and this is what the majority of the fishermen are spending the money on.”

Abdulrahman himself has been working as a fisherman since childhood. It’s a life he’s enjoyed, spending time on Yemen’s warm seas with his friends.

But the ambergris discovery has left a sour taste with other fishermen, who lament that the fish they catch is worth so much less than the precious substance cut from a whale.

“We can sell fish for around 1m rials in the best cases. Some of this we spend on fuel and to rent the boats, the rest of the money we share,” he said.

“But now the ambergris was sold for a huge amount, so fishermen are frustrated by the income they get selling fish.”

Gaber* wasn’t lucky enough to be one of the fisherman that found the ambergris, but those that did retrieve it gave him money nonetheless.

“The fishermen went sailing to fish, and their situation was very bad, so they prayed to God to help them and he accepted their prayers and suddenly they found the sperm whale,” Gaber said.

The fisherman pointed out that many of the men have children depending on them, and others don’t have enough money to marry and start a family, so the ambergris sale will alleviate their suffering.

'We inherited this job from our grandfathers and we can’t live far from the sea'

- Gaber*, fisherman

“All residents of the village were happy for the fishermen and we tried to help them in any way we can. When they sold the ambergris, they helped us with money and helped some families with medicines,” he added.

Most of the fishermen in al-Khaisah belong to the same extended family, and everyone was given some help.

“All residents of al-Khaisah work as fishermen, and even those who have different jobs go sailing to fish when they have free time,” he said. “We inherited this job from our grandfathers and we can’t live far from the sea.”

Even the fishermen who found the ambergris have stayed in al-Khaisah and are still setting out to sea every day with their colleagues.

The sea is unpredictable

Saeed Morie, a displaced fisherman from Hodeidah, was stunned when he heard about the ambergris, and is overjoyed that some of his colleagues have found wealth and a route out of the suffering that so many Yemenis live under.

“The sea is unpredictable. We pray to God and sometimes we get enough fish and sometimes don’t. That’s our luck that God gives us,” he told MEE.

“Those who can find a sperm whale are the luckiest fishermen, as they can be transformed from labourers who work for others to owners of boats who hire sailors themselves.”

Morie knows some of the men who discovered the ambergris, and said their lives have been changed in ways they could only dream of.

“I know some who now own boats after they sold the ambergris. But I also know some fishermen who lost their boats and lives in the sea because the wind is unpredictable. Working as a fisherman means adventure, which can be good or bad.”

The expertise that Hodeidah’s fishermen have in identifying sperm whales is now legendary - and those from Aden’s coast now hope to follow suit. Morie said the ambergris can either be found in a dead whale’s stomach, or it vomits it before dying, and he will be on the lookout next time.

“Usually fishermen have found amounts that don’t exceed four kilos of ambergris, but those ones in Aden are lucky and they found 127kg,” he said.

Abdulrahman, meanwhile, thanked God for bringing luck to him and his village - as well as a very special colleague.

“If not for that displaced fisherman from Hodeidah, we won’t have recognised the sperm whale and wouldn’t get anything. So it is our luck that God sent to us.”

*Names changed at the request of the interviewees.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].